This article is an onsite version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Monday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Joe Biden’s out of the race. In chorus, we trade folk immediately ask ourselves “what does this mean for trade policy?” and we all answer “dunno”. For the actual election probably not much, as it’s hard to imagine a sudden shift from Kamala Harris or whomever at this stage. Today I revisit a prediction I made three years ago about the immediate impact of Bidenomics on trade, and also look at the continuity in Europe. What else is new? Oh yes, turns out the critical global economic chokepoint wasn’t the Houthis blocking the Red Sea but a Windows update gone wrong. Who knew? Charted waters is on shipping costs. My question for you this week: what comes next for Democratic trade policy after Biden? Your guess is almost certainly better than mine. Answers to [email protected].

Get in touch. Email me at [email protected]

Slip Biden away

So that prediction from May 2021 again. I said that in the short-to-medium term, getting the US economy back to growth after the shock of Covid-19 was more important for trade than tariffs and regulations. I’m claiming vindication on this one, hence today replicating the headline from then with a change of tense.

It might seem odd for a trade columnist to say this, given I think a lot of his administration’s policy is mistaken — and often driven by unfortunate motives, namely cosseting the steel industry in the swing states. But Biden in his first term probably did more immediate good for trade than, say, the sort-of multilateralist, sort-of free-trader Barack Obama did in his.

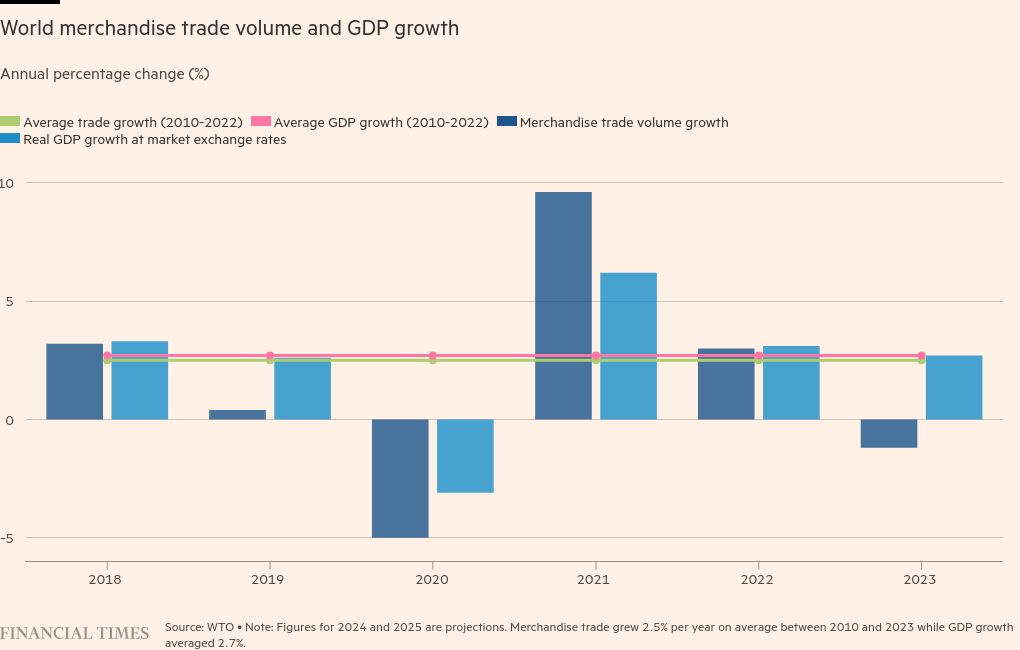

Over the short-to-medium term, trade (in services as well as goods) is driven more by demand than changes in efficiency promoted by policies on tariffs and regulation. Trade usually follows the economic cycle, but with a bigger amplitude.

The fastest decade for trade growth since the end of the cold war was the 2000s. Yes, that decade did start with China joining the World Trade Organization, but for the rest of the time between then and the financial crisis, there was a sense that trade policy was in crisis and lots of wailing and gnashing of teeth about the failure of the multilateral Doha round. Nonetheless, the low interest rates and low inflation of that era did the job.

Similarly, trade bounced back after the financial crisis, not because of trade policy, but because demand recovered (not as quickly as it could have done, to be clear). It happened again after Covid, as suppressed US demand for consumer durables uncoiled — so much so that it overwhelmed the US’s west coast ports.

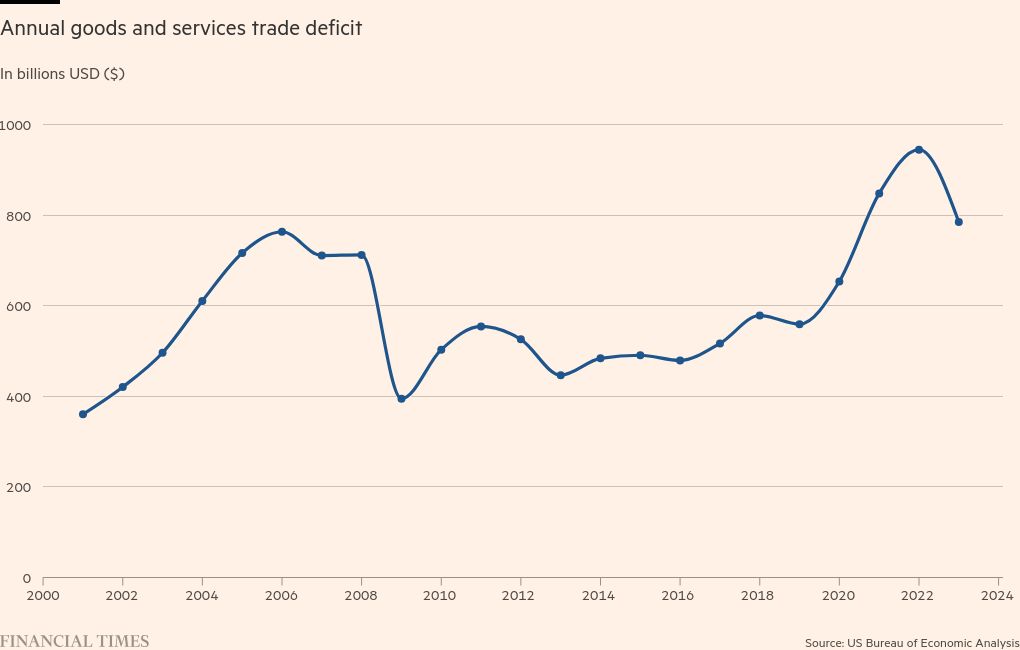

Hence Biden’s great achievement was the $1.9tn fiscal stimulus that supported a stronger recovery from the Covid shock than after the financial crisis, when a dangerous consensus of austerity took hold. The stimulus gave the economy a welcome jolt. (Joltin’ Joe, you might say.) Robust consumer demand meant the US goods trade deficit unusually went up, not down, during the Covid recession. And, despite completely mistaken, widespread warnings, the stimulus didn’t cause a great burst of inflation, prolonged high interest rates or another recession.

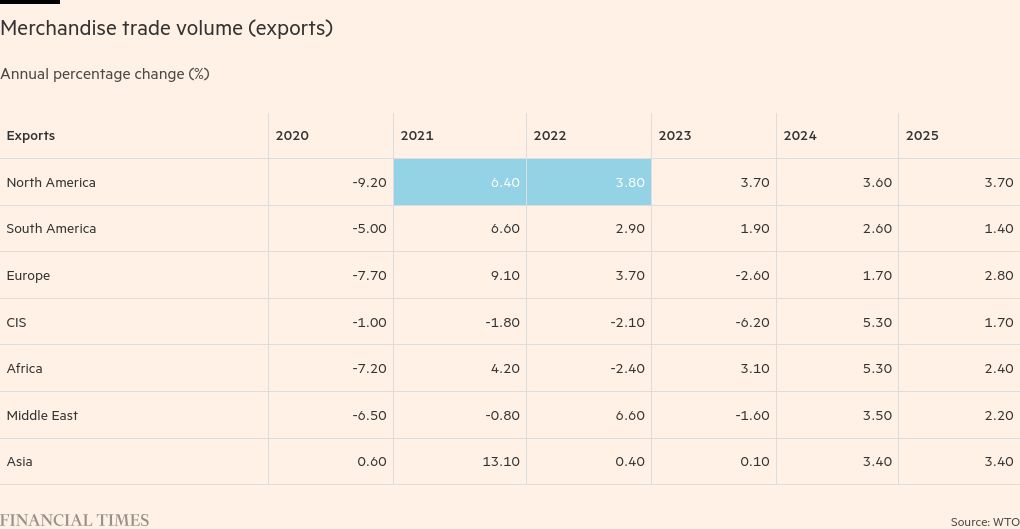

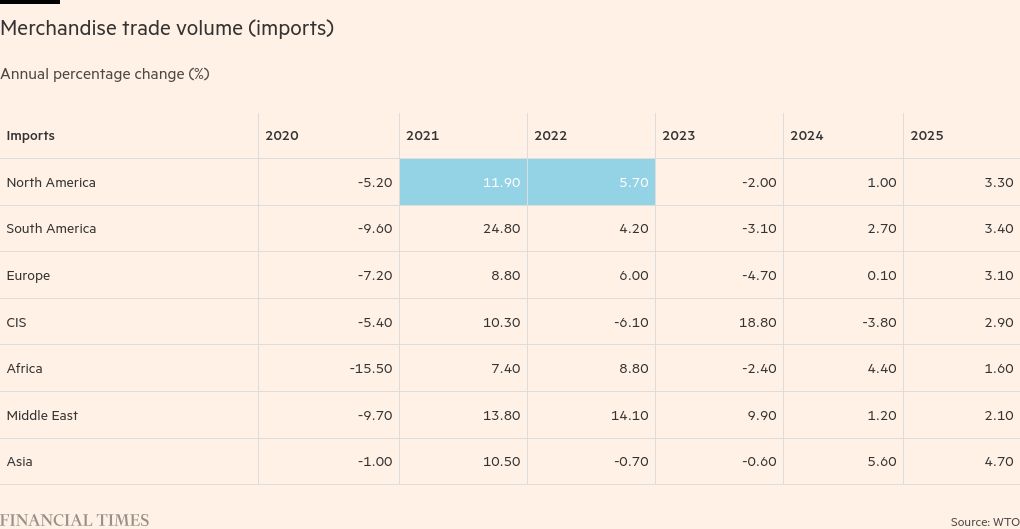

Check out these charts (taken from the WTO). Global GDP and merchandise trade bounced back very rapidly from the Covid shock, and the US did a lot of that work with its net trade deficit. A mercantilist president saved the world by boosting imports: ironic, but fortunate. Some of the global resilience in trade probably reflects companies finding ways round those mercantilist US-China tariff walls by routing supply chains through other countries: unintended, but also fortunate.

Yes, there are all sorts of long-term problems piling up. The trade frictions Biden has escalated with China, the US’s attempts to build an electric vehicle sector (and other green industries) behind tariff walls, its continued contempt for the WTO and its attempts to bully the EU into destroying its carbon pricing regime in the name of stopping climate change: all of these can do serious long-term damage to the trading system. But in terms of recovering from the immediate shock, the boy from Scranton did well.

I like EU just the way EU are

Over in Europe, a confirmed exercise in refreshingly tedious continuity. Ursula von der Leyen was reappointed as European Commission president last week without needing the support of the populist right. She didn’t signal any big changes to trade except maybe a bit more on climate deals and less on traditional trade agreements. (Also easing off on the green transition at home.)

As I’ve said before, there’s also not much in the new European parliament to make it more hostile to trade. The big issues facing the new commission will be what to do if Donald Trump gets elected and goes ahead with his crazy spree of tariff-raising, plus the pressure he might put on the EU’s eastern border by withdrawing support for Ukraine.

The other big deal, a technically tricky rather than politically partisan one, will be implementing programmes already in place — the deforestation regulation (which I wrote about last week) and the carbon border adjustment mechanism. As for passing the flagship EU-Mercosur deal, that’s largely in the hands of France.

One final thing: the perfect symbol of continuity will be the (probable) announcement this week of the European parliament’s international trade committee once again being chaired by Trade Secrets’ favourite, Bernd Lange. The veteran German trade unionist and Social Democrat is personally located somewhere around the median of the parliament’s attitude to trade and hence well positioned to judge which ideas will fly.

Lange has already done the job for a decade and has become an institution. Civilisations may emerge and fall, species may evolve and become extinct and mountains may rise and crumble into the sea, but Bernd Lange will still be chairing the European parliament’s committee on international trade.

Charted waters

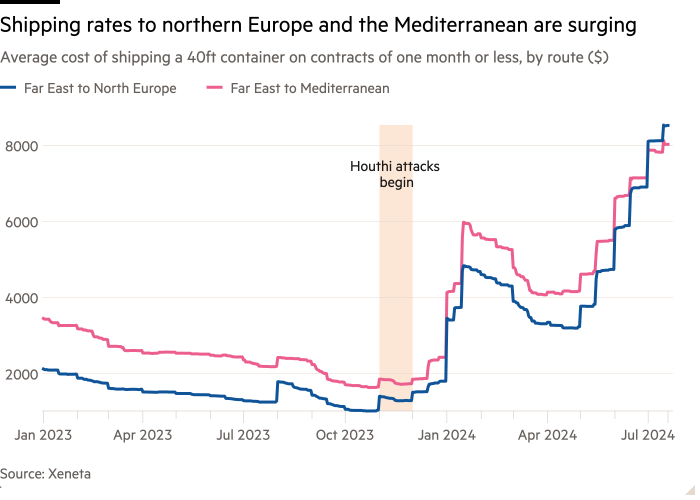

I’ve been pretty sanguine about the global effect of higher freight rates on trade and inflation, but even I’m beginning to accept that these numbers are quite a lot worse than expected.

Trade links

Ed Gresser from the Progressive Policy Institute compares Donald Trump’s tariffs to the Herbert Hoover Depression-era tariffs.

A draft WTO agreement on limiting fisheries subsidies is again in trouble, and again India (I know, I was amazed too) is the one holding things up.

My FT colleague Peter Foster looks at potential UK energy co-operation with the EU, at the end of the newsletter.

The FT editorial board opines that imported Chinese electric vehicles should be part of the green transition in the EU and US.

Tej Parikh makes the bear case for AI in the Free Lunch newsletter.

Trade Secrets is edited by Harvey Nriapia today

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here

The State of Britain — Helping you navigate the twists and turns of Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with Europe and beyond. Sign up here