Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The UK has a new government, with a huge majority. But only just over a third of the voters voted for it. Moreover, it has won power in a country that has lost confidence in democratic politics: recent polling for the independent think-tank, Demos, shows that “76 per cent of people have little or no trust that politicians will make decisions in the best interests of people in the UK”. This is a crisis for democratic politics, not just for politicians. It is in such seas of distrust that demagogues ply their trade in scapegoats and falsehoods.

Sir Keir Starmer will find it hard to turn around the tide of discontent. The promises he unwisely made on the way to power will, I have argued, make it still harder to build the desperately needed combination of performance and trustworthiness. Many things need to change, among them how the country governs itself. A centralised government dependent on a professional civil service is not going to be good enough. Citizens should be asked to participate more deeply. That could improve not just how the country is governed, but how it is seen to be governed.

In an excellent “Citizens’ White Paper”, Demos describes the needed revolution as follows, “We don’t just need new policies for these challenging times. We need new ways to tackle the policy challenges we face — from national missions to everyday policymaking. We need new ways to understand and negotiate what the public will tolerate. We need new ways to build back trust in politicians”. In sum, it states, “if government wants to be trusted by the people, it must itself start to trust the people.”

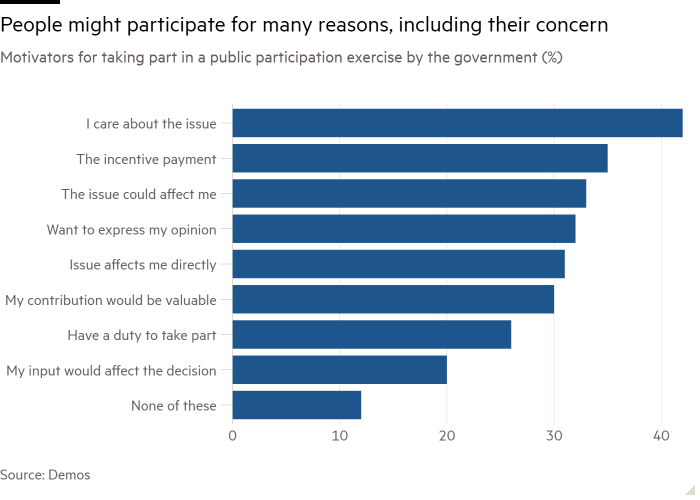

The fundamental aim is to change the perception of government from something that politicians and bureaucrats do to us into an activity that involves not everyone, which is impossible, but ordinary people selected by lot. This, as I have noted, would be the principle of the jury imported into public life.

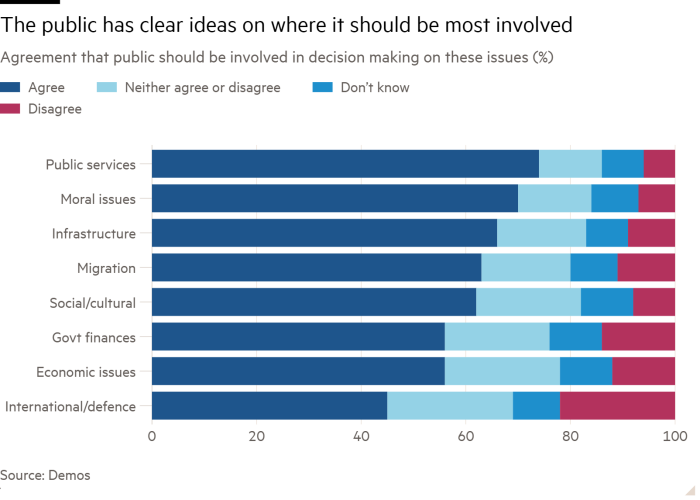

How might this work? The idea is to select representative groups of ordinary people affected by policies into official discussion on problems and solutions. This could be at the level of central, devolved or local government. The participants would not just be asked for opinions, but be actively engaged in considering issues and shaping (though not making) decisions upon them. The paper details a number of different approaches — panels, assemblies, juries, workshops and wider community conversations. Which would be appropriate would depend on the task.

What might be done to make this a reality in the UK? Ambitiously, the paper outlines the following six steps for the next 100 days: announce flagship panels to feed into the government’s five mission boards (for growth, clean energy, crime, opportunity and the NHS); create a standing pool of citizens from which mission boards and departments could draw; create a hub of expertise on participation in government; announce a programme of flagship citizens’ assemblies; create levers for participatory policymaking within government, such as training and support; and involve citizens in hearings by parliamentary select committees.

In the longer term, it suggests, there could be three more steps: create a duty to consider participation; involve citizens in scrutiny of past legislation; and create an independent mechanism governing how all this might work.

This would evidently mark a large change in how government works. It would also cost money, though less than £31mn a year in the first year, according to the paper, which is insignificant in total spending of £1.2tn. Processes would take longer and be more complex. So, the question is whether they would be any better than today.

We cannot know without trying. But there are powerful reasons why they might be, all laid out in the paper. First, ordinary people have lived experience that ministers, civil servants and the normal range of experts will lack. By participating, they can bring this knowledge into the heart of decision-making. Second, by debating on complex issues and interrogating expert witnesses, citizen bodies might reach a degree of consensus on hugely controversial issues, such as planning controls, “net zero”, prisons, immigration and assisted dying. This might then help guide government on such matters.

Third and most important, the engagement of ordinary people could make the public feel that governance is no longer just done by remote figures, but is something in which people like themselves are also engaged.

If we could credibly feel that today’s representative democracy is a huge success, none of this need be considered. But it is not. So it should be, now.

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on Twitter