This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning. Explore all of our newsletters here

Welcome back. I imagine that, after five consecutive weekends consuming news and analysis about France, readers of this newsletter may want a change of diet. Off we go across the Rhine for a look at what’s happening in Germany.

Two months ago, the Federal Republic marked its 75th birthday. There was much to celebrate: the republic is the most enduring, stable, prosperous and democratic polity that Germany has had since national unification in 1871.

Still, complacency would be misplaced, as many Germans are quick to acknowledge. At home and abroad, the old certainties that afforded them security and a quiet life are giving way to threats and challenges that do not have easy solutions. I’m at [email protected].

Life after Merkel

There was another birthday in Germany this week — former chancellor Angela Merkel, who ruled from 2005 to 2021, turned 70 on Wednesday. The tributes flowed freely.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz said his predecessor “can look back on an impressive career”. Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the head of state, mentioned the former chancellor’s upbringing in communist east Germany, observing: “The special thing about Merkel’s 70 years is that it can be divided in half precisely between her first 35 years behind the Iron Curtain and the latter 35 years in much-longed for freedom.”

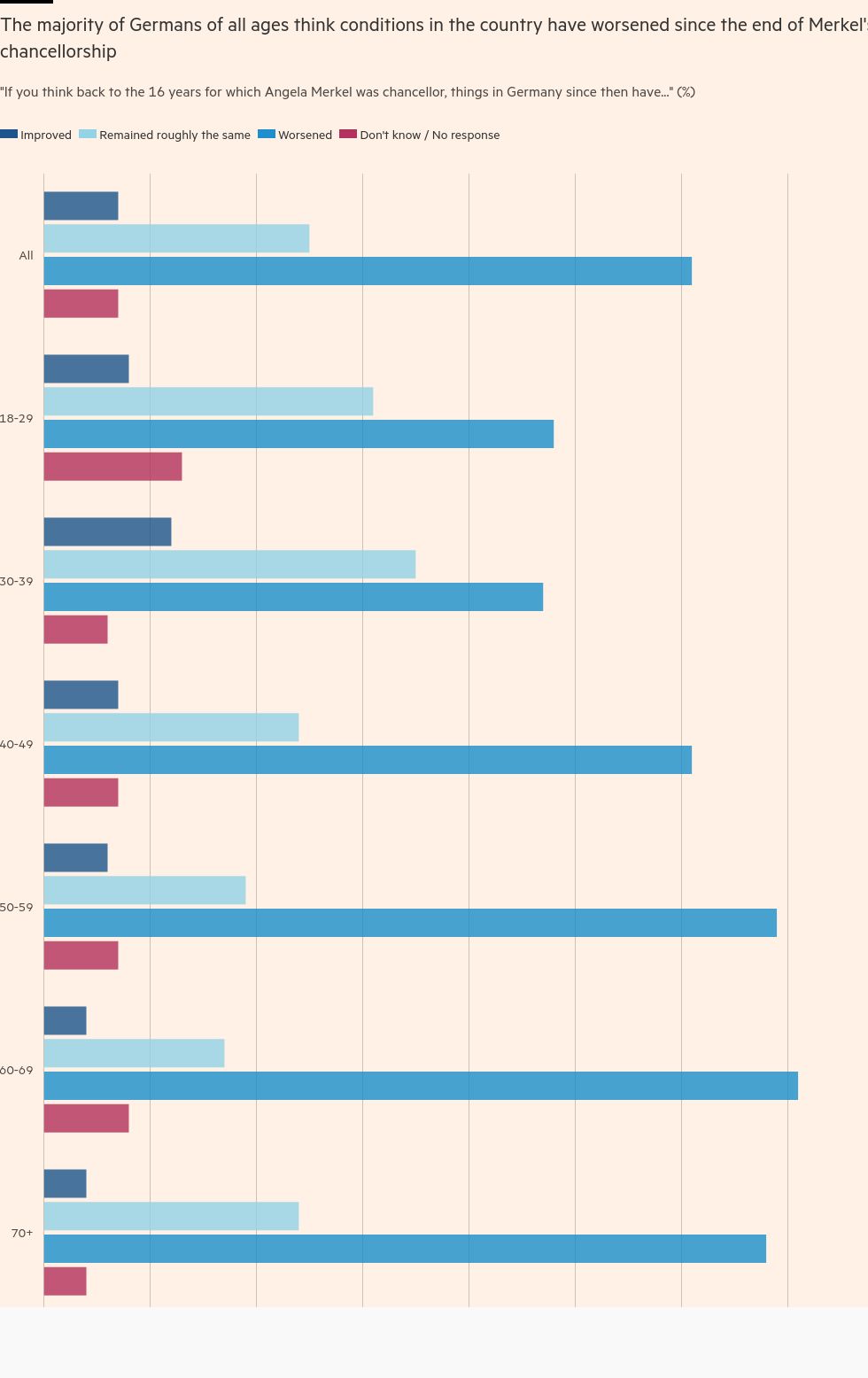

By and large, the German public seems to have fond memories of Merkel, too. In the YouGov poll below, we see that 61 per cent of respondents think conditions in Germany have grown worse in the four years since she left office. This mood is particularly pronounced among older Germans (69 per cent for the 50-59 age group, 71 per cent for those aged 60 to 69, and 68 per cent for those over 70).

In certain political and intellectual circles, however, opinions of Merkel are less forgiving.

Her foreign policy, based partly on forging close economic ties with Russia and China, has come under severe criticism since Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Her emphasis at home on caution, consensus and coalition-building is seen as having left Germany in serious need of economic reform as well as having opened up space for rightwing extremism.

Craving for harmony, conflict with friends

However, the important point is that Merkel’s policies, and the assumptions behind them, were in many ways shared by the rest of Germany’s political establishment, not to mention the general public (she won four elections in a row from 2005 to 2017).

Bernhard Schlink, an acclaimed German novelist, drew attention to this in a 2018 interview with the broadcaster Deutsche Welle. Germans tend to avoid conflict and crave harmony, he said.

Regarding Merkel’s foreign policy, Sigmar Gabriel, a Social Democrat who served as her vice-chancellor and foreign minister, engaged in a bit of self-criticism when he said after the Russian attack of 2022:

“To be honest, we Germans never believed the war in Ukraine would happen, until it did. The success of Germany’s economy and society is founded on successful economic integration and the conviction that the closer the economic ties are, the safer the world will be. That was obviously a gross misjudgment.”

Annalena Baerbock, a Green politician who is foreign minister in Scholz’s three-party coalition, put this point even more forcefully in April in a speech to German bankers:

“For us — and I am speaking here for all politicians in general . . . wrong decisions and not heeding respective warnings has not only resulted in substantial diplomatic damage and loss of trust — these things I experienced during my initial months in office, especially in the Baltic — but has also posed an enormous threat to our own security.”

France: Germany’s European pillar shakes

Scholz’s government has taken important steps towards correcting Germany’s errors by lining up with its western allies in support of Ukraine and by readjusting its relationship with China.

No doubt more could be done on both fronts, especially China, as Andreas Fulda writes in his powerfully argued new book Germany and China: How entanglement undermines freedom, prosperity and security.

However, what is really unnerving for policymakers in Berlin is that, just when they see the need for a solid front of western democracies against hostile or unpredictable autocracies, the two pillars of the Federal Republic’s foreign policy since the 1950s — the US and France — are in domestic political upheaval.

For decades, close co-operation with France has been the very essence of Germany’s EU policies. The two countries have not always seen eye to eye, but the view in Bonn and later Berlin was that any difficulties could be surmounted as long as a certain pro-European consensus prevailed in Paris.

Now, after the retreat of President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist forces and the rise of the radical left and right in France’s snap legislative elections, the outlook looks more troubling — as set out in this excellent collection of articles for the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

On one hand, the radical left and right entirely lack the Germanophile instincts of important segments of France’s political and bureaucratic establishments. Neither commands a majority in the French legislature, but their views will count for something.

On the other hand, with Macron’s political career in decline, the pressures are building in France for a more nationalist-tinged approach to EU affairs. In his article for the SWP essay collection, Paweł Tokarski comments:

“The short and chaotic election campaign has contributed to a further deterioration in the quality of public debate on economic issues in France . . . French economic policy is becoming increasingly protectionist and statist.

“It is very unlikely that the next governments will enthusiastically promote the integration of the internal market or want to conclude new EU trade agreements with third countries. All this will make Paris an even more difficult and unpredictable partner for Berlin.”

The US: Germany’s Atlantic pillar shakes

Across the Atlantic, the prospect of a second Trump administration fills mainstream German politicians with trepidation.

The US has been the bedrock of the Federal Republic’s security since the cold war, but in his first term Donald Trump was arguably more hostile to Germany than to any other European Nato ally. He drew some scathing criticism from Scholz in February when he appeared to question the US commitment to transatlantic collective security.

An extra headache for policymakers in Berlin is that political trends in the US, like those in France, play into the unsettled political climate in Germany itself.

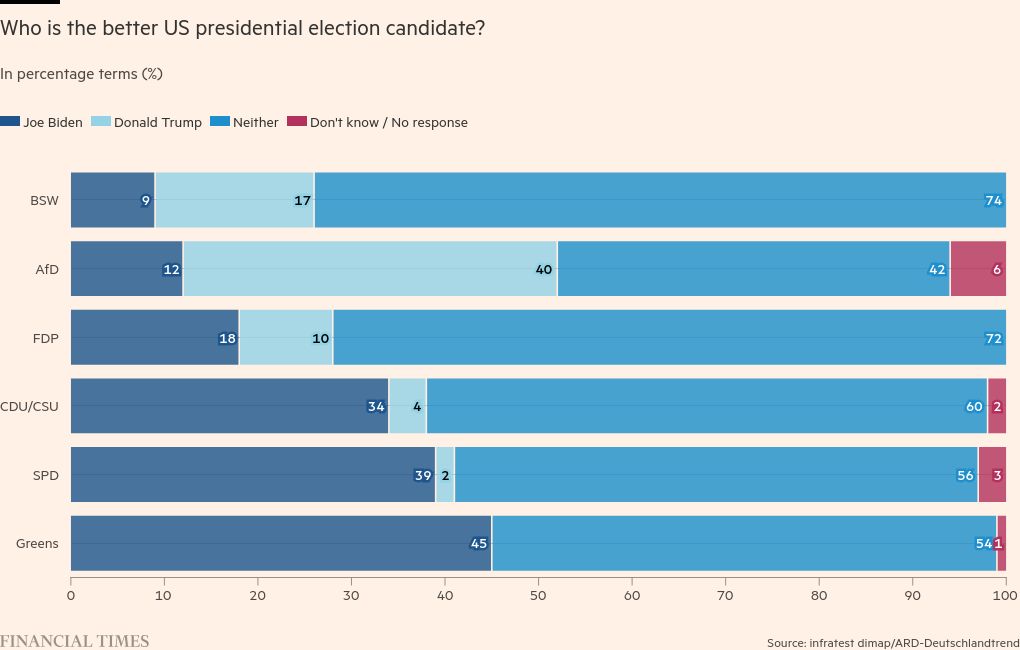

In the poll below, we see that supporters of Germany’s mainstream parties — the Social Democrats, Greens and opposition Christian Democrats (CDU) — either favour Joe Biden’s re-election as US president or are neutral. By contrast, supporters of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) favour Trump.

The AfD is still very far from gaining a seat at the table of national power in Germany. The taboo against the far right remains stronger in Germany than probably all other European democracies.

However, the AfD achieved its best ever nationwide result in last month’s European parliament elections, finishing second behind the CDU. In September, three eastern German states — Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia — will hold elections, and opinion polls indicate the AfD will either win them or come a close second.

German defence spending in a mess

Germany could put its relationship with the US on a stronger footing if it fulfils its promises to boost defence expenditure. But here the picture is not exactly reassuring.

Throughout the Merkel era, Germany never came close to meeting Nato’s target of spending an annual 2 per cent of GDP on defence. The trend is now upwards, but even Boris Pistorius, defence minister, is not satisfied that enough is being done.

This week, it emerged that Germany’s draft 2025 budget may result in a reduction in direct military aid to Ukraine — although the gap may be filled with weapons supplies bought with profits generated from frozen Russian assets.

Part of the problem lies with Germany’s constitutionally enshrined commitment to keeping the federal budget in or near balance — another legacy of the Merkel era, excoriated by the FT’s Martin Wolf this week.

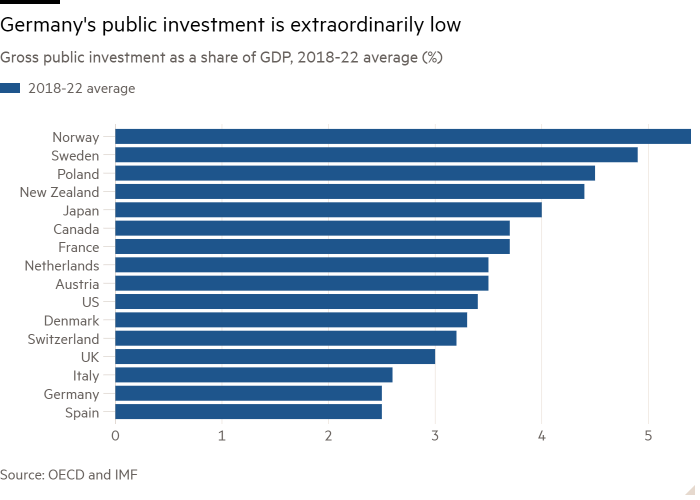

Martin’s column includes the chart below, which shows how Germany’s so-called “debt brake” has resulted in sharply lower levels of public investment than in other advanced western economies.

Removing the “debt brake” is an obvious way both to boost badly needed investment in German infrastructure and to increase military spending. Each step would show that Germany is stepping up to the plate in these troubled times. Whether the brake will be ditched any time soon, I am not so sure.

“Your turn, Berlin: a German strategy for Europe” — a commentary by Josef Janning for the German Council on Foreign Relations

Tony’s picks of the week

The venture capital arm of US chipmaker Intel has emerged as one of the most active foreign investors in Chinese artificial intelligence and semiconductor start-ups, the FT’s Tabby Kinder, George Hammond, Demetri Sevastopulo and Ryan McMorrow report

Russia’s casualties in the Ukraine war have been so high that the economic and demographic effects will weigh on the country for many years to come, Thomas Lattanzio and Harry Stevens write for the War on the Rocks site

Recommended newsletters for you

The State of Britain — Helping you navigate the twists and turns of Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with Europe and beyond. Sign up here

Working it — Discover the big ideas shaping today’s workplaces with a weekly newsletter from work & careers editor Isabel Berwick. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe