In the mid-1840s, in a melancholy mood about the series of modernisations he was witnessing in Paris, Honoré de Balzac wrote in his unfinished novel Les Petits Bourgeois: “Alas! the old Paris is disappearing at a frightening rate.” Sixteen years later, during Haussmann’s whole-scale renovation of Paris between 1853 and 1870, Charles Baudelaire would cast this kind of transformation as the essence of what it means to live in a city, writing in Les Fleurs du Mal: “The form of a city changes, alas! more quickly than the human heart.” Alas, alas!

It is now our own turn to wonder what kind of Paris we are bequeathing the future. As part of the “Grand Paris” project, the city is currently undergoing a radical shift from being a small city of 2.2mn people living in 105 square kilometres into a metropolis encompassing 6.7mn people over 762 square kilometres. New Métro lines have been built and are soon to open, allowing Parisians to move more quickly than ever between the city and its suburbs; gentrification is already under way in suburbs such as Pantin, Montreuil or Aubervilliers, and housing prices are correspondingly poised to increase.

Now, with the Olympics about to begin, the world’s attention is turning to Paris — or rather to its suburbs, where most of the events will be held. And one of the major stories emerging in advance of the Games is the very real impact this is having on thousands of homeless people, sex workers and migrants who are being bussed out of the capital and threatened with deportation in preparation for the visitors and cameras.

Like Balzac and Baudelaire in their day, writers and journalists have been paying keen attention to these shifts, asking not only how the city is changing, but why, and who benefits. The two new books considered here — Justinien Tribillon’s The Zone: an Alternative History of Paris, and Eric Hazan’s Balzac’s Paris: The City as Human Comedy — are among several recent titles that grapple with the Paris we have inherited, and the future that might be imagined for it.

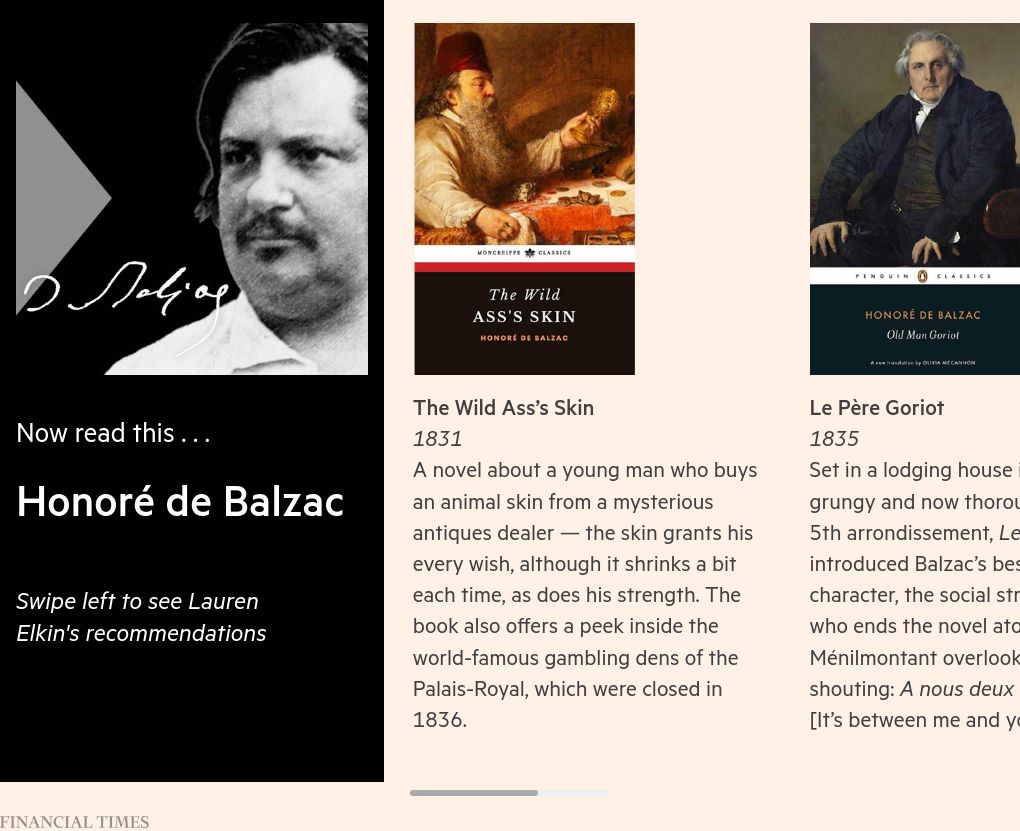

What they have in common is a commitment to combating the image of Paris as some rarefied cobblestoned space, where everyone is thin and chic and reads philosophy while smoking in a café. Paris could be a “fairyland”, Balzac wrote, but it was also a muddy, dirty place; witness Rastignac in his 1835 novel Le Père Goriot, who when travelling from one part of the city to another had to take “a thousand precautions to avoid being spattered with mud . . . had to have his boots polished and trousers brushed at the Palais-Royal”.

Broadening our understanding of Paris was Eric Hazan’s mission after turning to writing at the age of 66, following a career as a paediatric heart surgeon (and as the founder of the publisher La Fabrique). Hazan, who died in June at the age of 87, specialised in the impact of repressive French state policies on the shape of Paris, studying them in a series of books including The Invention of Paris (2010), A History of the Barricade (2015) and A Walk Through Paris (2018), a journey on foot through the “red belt” of the Communist towns to the south of the city.

Centuries of political upheaval, large-scale renovations, and cultivated resentment and racism have seen the classes dangeureses moved out to the suburbs, and the centre of the city claimed by the wealthy. To understand Paris, argues the urbanist Justinien Tribillon, “you have to hear the voices of the Zone”, by which he means the space between the city and the suburbs. In his searing account of life in the interstices of the capital for the working class and North African immigrants from the mid-19th century to the present day, Tribillon proves a worthy successor to Hazan, although his guiding spirit is more Victor Hugo than Honoré de Balzac.

The Zone was a byproduct of the Thiers wall, a military fortification built in 1841, which was eventually replaced by the present-day ring road, known as the périphérique, inaugurated in 1973. Tribillon’s book is the first in-depth history of this space, where a layer of makeshift housing cropped up. Ostracised for their lack of cleanliness or morals, the zonards and their homes “became the civilization’s antonym: on the edges of the city of light stood its abyss, its dark forest, its dump, its no-man’s land”. Haussmann’s beautified city centre, with its long elegant boulevards, ornate balconies, and wrought-iron benches were not for them.

Well-meaning activists and civil servants tried to address the problem of the Zone throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. In the 1940s, a “green belt” was pitched as a form of “social hygiene,” allowing the working classes who lived at the edge of the city to benefit from fresh air and space. But planting trees is not in itself a benevolent act; Tribillon persuasively shows that a belt can also be a “buffer”, looking at the roots of 20th- and 21st-century green urban policy in Vichy France and the equivalence it drew not only between morality and disease prevention, but also “ancestry, race, bloodline and religion”. You have only to remember then-interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy in 2005 promising to clean up the suburbs with a power hose to see that some of these ideas are still with us.

The ring road was itself initially conceived, in 1954, as a part of the greenbelt, meant to be lined with trees and pavement. But the role of nature soon took a back seat, and the périph turned into “the least desirable piece of real estate for the whole of Paris”.

Towards the end of Tribillon’s book, the author takes a walk in a housing project — on a street called the rue Honoré de Balzac — in the northern suburb of La Courneuve, one of the sites of the upcoming Olympics. For Tribillon, these projects — les grands ensembles, as they’re called — are a failed opportunity for the state to build social housing that is truly functional, served by transport and amenities, inviting a mix of social classes; instead, the good intentions of the original planners were scuppered by diminished budgets and a commitment to building not well but quickly. What Tribillon calls “the myth of the banlieue rouge” is a result not of implacable social forces, but ideology and lack of political will.

Where Tribillon sketches a history of Paris’s outer periphery, Hazan takes us on a tour of its historical centre. Hazan’s Parisian “itinerary” of the Human Comedy, Balzac’s epic cycle of novels, stories, and essays about the French society of his time, takes us through Paris under the July Monarchy (which lasted from 1830-1848, under Louis-Philippe, the last French king). Balzac knew the city intimately, having lived in no fewer than 11 official residences there between 1829 and 1847, the period during which he wrote the 91 works contained in the Human Comedy.

Balzac’s Paris can be easily divided in two: old and new Paris. The older Paris, writes Hazan, “is contained within the arc of the Grands Boulevards […] Still largely medieval in its architecture and the jumble of its streets, it had hardly changed since the end of the Ancien Régime”. But in his own day, Balzac saw another Paris take shape “between the boulevards and Wall of the Farmers-General that bounded the city. […] The emergence of entire districts, financial speculation, the constructions of the nouveaux riches — this is the background noise of The Human Comedy, an incomparable picture of the formation of a city.”

Although he did not live to see Haussmann’s massive overhaul — he died three years before the prefect of the Seine came to power — Balzac did write about the development of districts such as the Chaussée-d’Antin, the Nouvelle Athènes, the areas around Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, Saint-Georges, and Europe, which was to become, Hazan writes, “the liveliest, most amusing, richest . . . most artistic area of Paris — and the epicentre of The Human Comedy”. Hazan tells us that Balzac took a stroll to the Thiers wall one day in the early 1840s, noting the fortifications and the pretty roads on either side of them, “pretty as a mirror”, but if he saw the Zone, he said nothing of it.

What sustained Balzac’s interest were his fellow Parisians, their disputes and quarrels and wars, their greed and their avarice, their passion and their misfortune. No one is ever bored, in Balzac’s Paris; all his characters are, as Baudelaire put it, “loaded with willpower up to their eye-teeth”. In a line that wouldn’t be out of place in Tribillon’s book, Balzac saw the city of Paris as “a vast field constantly stirred by a storm of interests” — never a mere backdrop, in Hazan’s view, but an intrinsic part of the people who live there, as much as “their physique, their dress, or their psychology”.

For readers unfamiliar with all (or any) of Balzac the book may be difficult to follow; these denizens of his city waltz in and out of the narrative, coupling and uncoupling, striving and skulking, gambling and dying. But it is a journey worth taking, reminding us that through its many renovations, Paris has remained a place where “everything smokes, everything burns, everything shines, everything bubbles, everything flames, evaporates, is extinguished, rekindled, sparkles, fizzles and is consumed”.

Balzac’s Paris: The City as Human Comedy by Eric Hazan, translated by David Fernbach Verso £15.99, 208 pages

The Zone: An Alternative History of Paris by Justinien Tribillon Verso £18.99, 208 pages

Lauren Elkin is the author of several books, including ‘Flâneuse’ and ‘Scaffolding’

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen