Flush from their unexpected victory in second-round elections, France’s leftist parties have been united in rejecting President Emmanuel Macron.

But as the motley Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP) alliance seek to form a minority government, its parties are scrambling to keep unity and overcome divisions — not least over the role of far-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

On Monday, party chiefs in the leftist bloc, who pulled together for the parliamentary vote after fracturing ahead of last month’s European elections, said they would together propose a prime minister to Macron this week.

No choice has been made, but it has already proved a flashpoint: Mélenchon’s far-left party staked a claim and implied their leader could be an option, only to have their alliance partners reject him as too polarising.

“The NFP will apply its programme, nothing but its programme and all of its programme,” Mélenchon said after the vote.

The alliance has maintained it will not cut deals if that means diluting their progressive programme, including bringing back a wealth tax and repealing Macron’s unpopular increase to the retirement age.

But the NFP’s lead in the National Assembly is slim. With about 180 seats, the grouping is far short of an outright majority of 289. Without allies, it would immediately be vulnerable to a no-confidence vote.

One opposition official called the idea that the left could govern alone “totally delusional”.

Macron’s centrist alliance, which came second with about 158 seats, has suggested it would be open to a coalition stretching from the centre-left to the conservative right.

Macron’s grouping, however, has ruled out working with Mélenchon’s party, while the NFP appears to have closed the door for now.

“There will be no coalition that would betray the French people’s choice and extend the policies of Macron,” said Socialist party chief Olivier Faure in a celebratory speech on Sunday.

Green leader Marine Tondelier was just as determined on Monday. “There is an adage in politics that should be our north star in the NFP — never forget who elected you, why they elected you, and what they elected you to do.”

Beyond the show of unity, the parties were still thrashing out whom they would propose as prime minister, and what would be their priorities.

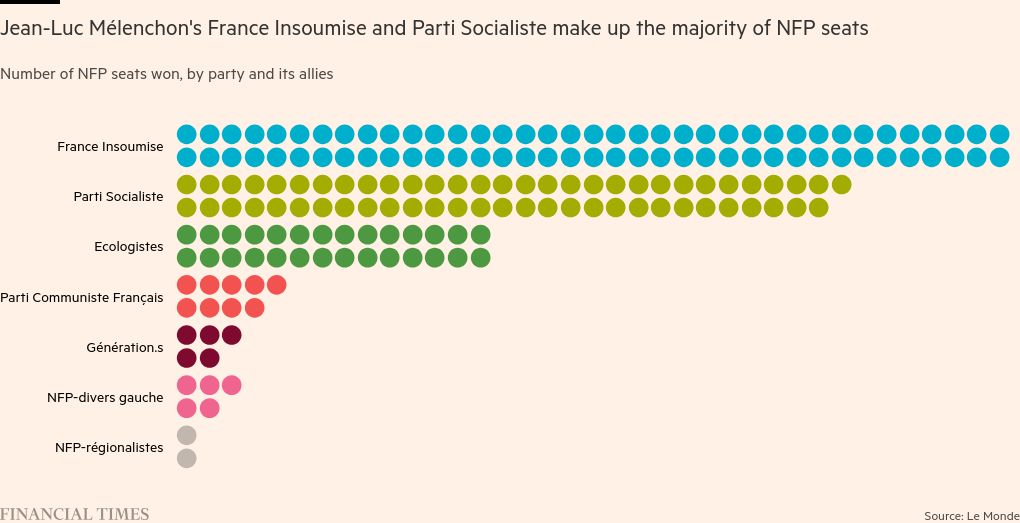

Hastily arranged in the days after Macron called the snap election in June, the NFP bloc includes Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (LFI), the centre-left Socialists and Greens, and the Communists.

To bring the alliance to life, they papered over differences on international issues such as the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Centre-left candidate Raphaël Glucksmann had criticised Mélenchon and his party ahead of European elections in June for what he called their softness on Russia and their criticism of Israel after Hamas’s October 7 attacks.

The alliance also agreed to a radical, heavy tax-and-spend programme.

But Sunday’s vote has also altered the dynamics within the leftist bloc. Mélenchon’s LFI was in the driver’s seat within the previous grouping in the parliament elected in 2022, but the latest vote boosted the more moderate parties, especially the Socialists, who doubled their ranks to 59.

The constitution does not spell out how the president designates a prime minister, but they customarily call on the party with the most MPs to form a government.

A person close to Macron said on Monday, however, that the unprecedented results — in which none of the three blocs came close to an outright majority — meant the usual practice might not apply.

Mélenchon’s own party even has divisions within. A handful of its MPs have fallen out with the leader over his domineering style and say they will not join the group in the new assembly, diluting the far-left’s ranks.

The rebels include prominent figures such as François Ruffin, an activist turned MP in the Somme region, and Clémentine Autain, another MP from Seine-Saint-Denis.

Ruffin said that Mélenchon had been a “millstone around their necks” by turning off voters.

Mélenchon earned his stature as the left’s standard-bearer in the past decade as a powerful orator and proponent of radical policies. He argued these were needed to break from the compromises of the moderate left, symbolised by the presidency of his rival, the Socialist François Hollande.

Mélenchon has run for president three times, improving his score each time, and almost made the second round against Macron in 2022.

Based on that performance, he united the left in what was then known as the Nupes alliance. But his brand of anti-capitalist, revolutionary politics eventually isolated his party on the far left, and his troops fell out with their moderate partners.

Those differences were on display during the European elections, when the leftist parties all ran separate lists.

Now Glucksmann, of the centre-left, is again pushing for a different approach to the alliance from Mélenchon, hinting the left might need to seek allies.

“We are in a divided assembly and so we will have to behave like adults,” he said. “That means we’ll have to talk, discuss, have dialogue and to reach out.”

Macron and his centrists are betting that the leftist alliance will splinter, which could enable them to forge a governing accord with its moderate parties.

François Bayrou, a longtime ally of Macron, predicted the NFP would break apart because its factions have “attitudes and policies that are incompatible”. He added: “When Glucksmann speaks, he says the opposite of what Mélenchon does.”

Several Socialists and Greens argued that a future minority government would need a prime minister able to forge alliances and make deals with the opposition — not Mélenchon’s strong suit.

Stéphane Troussel, a leading Socialist and president of the Seine-Saint-Denis department, has recommended Faure, Tondelier or Ruffin as potential leaders, as well as Boris Vallaud, a leading MP for the Socialists.

But given that it is far short of a majority, the prospect of any such leader being able to put the alliance’s sweeping programme into action appears slim.

Along with unwinding Macron’s pension reform, the NFP has promised to boost the minimum wage and spend heavily on education, healthcare and combating climate change. To fund its programme they would look to the wealth tax and reform the flat tax on investments.

Thierry Pech, director of the left-leaning Terra Nova think-tank, said the leftist alliance would have to wake up to reality.

“The only way to govern is to bring together a broader group in the National Assembly so as to be able to survive a no-confidence vote,” he said. “I think they will realise quite quickly that they have to make major concessions.”