Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This is part of a Data Points series on the UK election

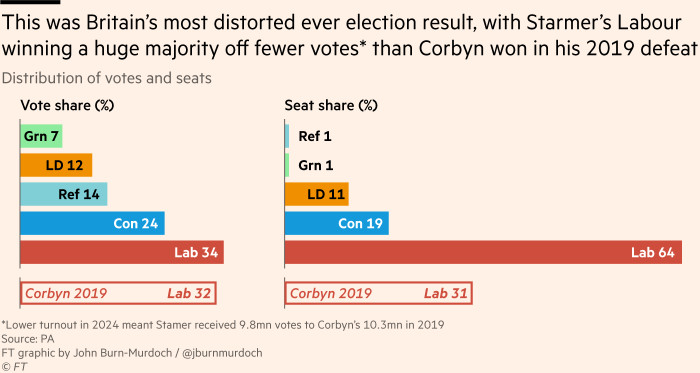

Four and a half years ago, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party received just over 10mn votes in the UK’s 2019 general election — only a third of all that were cast. This performance resulted in Labour winning 202 seats in the House of Commons, its lowest tally since the 1930s.

Yesterday, Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour party received half a million fewer votes than in 2019, again only a third of the popular vote. This performance has been rewarded under our first-past-the-post electoral system with a huge majority and 412 seats so far, the second-highest tally in the party’s history.

Fear not: I don’t mean to suggest Corbyn was robbed of a victory and a stint in 10 Downing Street. I am merely highlighting how Britain’s increasingly broken voting system can build wildly different narratives around similarly tepid levels of popular support.

In one sense all that matters now is that Starmer and Labour are in power. They will have the time and space to pursue their policy agenda and deliver on their promise of change. But if the past four and a half years have taught us anything, it is that a fragile coalition of contingent support can be dangerous, creating an incentive to say popular things instead of doing unpopular but necessary things.

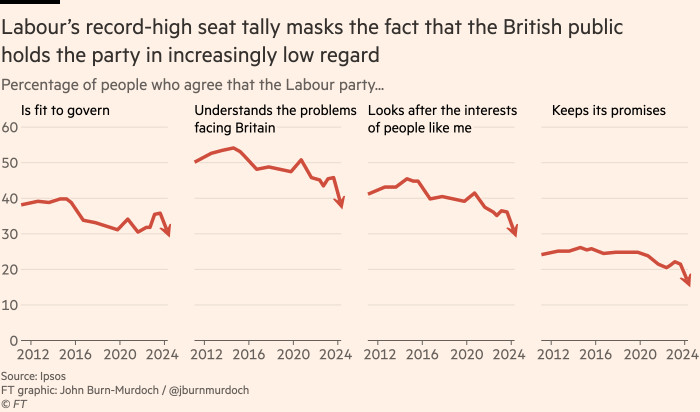

Beneath the surface of this historic Labour victory, the signs are ominous. The share of Britons who think Starmer’s party understands the problems facing the UK is at a record low, as is the share who say Labour keeps its promises; both figures are much lower than they were for Boris Johnson’s government when it took the reins.

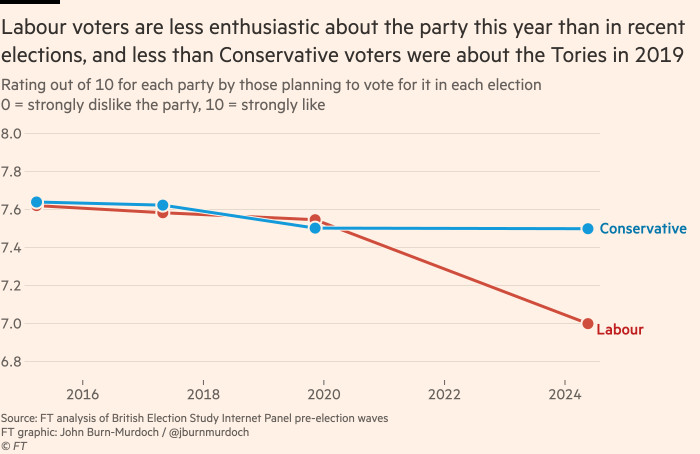

Perhaps most notably, a huge 48 per cent of those who intended to vote for Starmer’s party said the main reason was to get rid of the Tories, with far fewer giving a positive motivation relating to Labour and its policies.

Seat counts have dominated the narrative of this election more than any before it, facilitating comparisons to Tony Blair’s 1997 landslide. Look deeper, though, and the similarities with 1997 fade. Starmer has much less public goodwill than the incoming Blair, and is inheriting a country in a far worse state.

All of these underlying vulnerabilities mean that if Starmer is to succeed where Johnson failed, he will have to deliver tangible improvements quickly if he is to keep his broad coalition of support together. On some issues he may be lucky. Voters’ most urgent demand relates to the cost of living; without lifting a finger Starmer is likely to see inflation continue to recede and interest rates cut.

After that things get much more tricky. Another of voters’ key demands is for a better performance on immigration and asylum, which is where the contradictions in Labour’s coalition could really come to the surface.

For all of the Conservative strife on the issue, data shows that the overwhelming majority of their 2019 voters at least wanted the same thing: a reduction in immigration numbers and more control. It’s not nearly as simple for Labour.

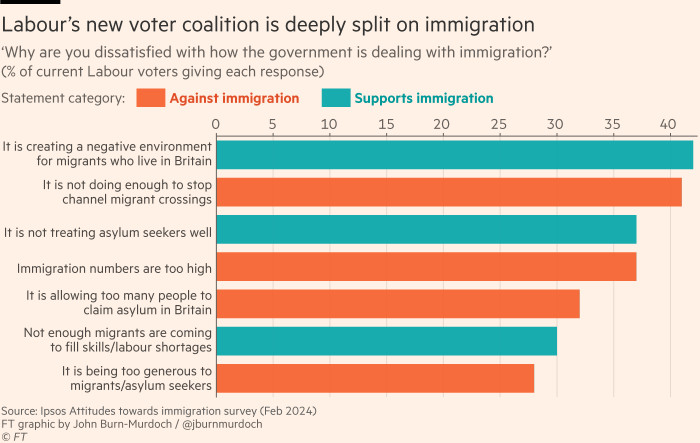

The clearest illustration of the tightrope Starmer will have to walk here is the way Labour supporters are split into diametrically opposed factions. About a third are angry that the Conservative government created a negative environment for migrants already in the country and want Britain to take in more immigrants. But another 40 per cent identify the problem as too much immigration and too many people allowed to claim asylum.

Almost any position Starmer takes will anger one of these groups. More than 100 Labour MPs now represent constituencies where the right, should the Conservatives and Reform UK unite or ally, would unseat them at the subsequent election. This means that the progressive voters’ side of the debate is likely to be the one that loses out. Nobody should be surprised if the very same split that we’ve seen on the right is mirrored on the left by the next election, with Labour voters peeling off to the Greens and independents.

Labour’s towering majority is capturing attention for now, but it is built on weak foundations. As James Kanagasooriam, chief research officer at polling firm Focaldata puts it, the coalition of voters that has put Starmer in 10 Downing Street is better understood not as a skyscraper but a sandcastle. As the tide comes in over the next few years, it could well be washed away, just as the Conservative party’s has been this week.