Hurricanes are the most powerful forces of nature on our planet. They can produce winds upwards of 275 km/h or stronger, along with intense rainfall and storm surges. And these effects can be felt for hundreds of kilometres from the centre of the storm.

Climate scientists believe that, as we continue to pump more and more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which warms the planet including our oceans — hurricanes are changing.

Some of the effects of climate change include hurricanes producing more rainfall, moving further inland in the Atlantic, and — more concerning to many climate scientists — rapid intensification.

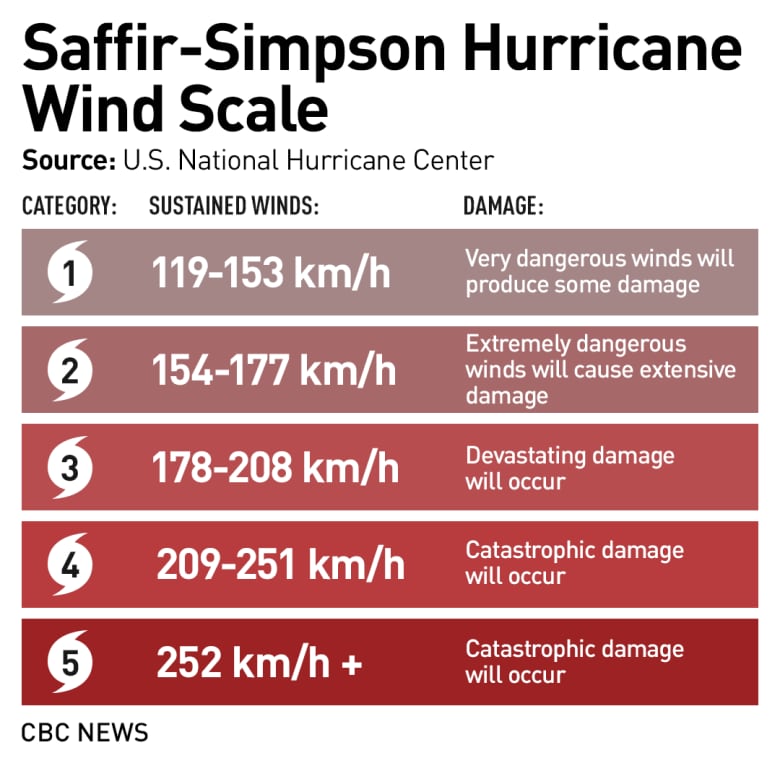

Last week, Beryl went from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in just 24 hours, eventually jumping to a Category 5. It was the earliest Category 4 and 5 on record for the Atlantic basin.

Along with two other rapidly strengthening storms last season, that’s three instances of rapid intensification in just five hurricane months (the season runs from June 1 to November 30).

“Based on the data that we have, over the last few decades, it used to be a really rare situation that a hurricane or a tropical storm would increase in intensity over 24 hours by such a large amount,” said Gabriel A. Vecchi, professor of geosciences at Princeton University in New Jersey.

“It’s becoming a more and more common event.”

What is rapid intensification?

The U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) defines rapid intensification as “an increase in the maximum sustained winds of a tropical cyclone of at least 30 kt [56 km/h] in a 24-hour period.”

However, some climate scientists say that there is no hard and fast rule.

Just like how a hurricane doesn’t suddenly jump in danger if it passes the threshold between Category 4 and 5, there isn’t one useful measure of “rapid,” said Andra Garner, assistant professor in the department of environmental science at Rowan University, in Glassboro, New Jersey.

“So you know, I think there is nuance there. And, you know, you always kind of need to keep that in mind that just because it doesn’t specifically fit the definition, that doesn’t mean it’s not still a dangerous storm.”

Hurricanes form from atmospheric disturbances and warm, tropical water. You can think of warm water as the fuel for hurricanes.

“When we get up in the morning, we have our cup of coffee to kind of get us going. That caffeine is really important for a lot of us,” Garner said. “For our hurricane, you’ve got those warm ocean waters that are kind of like the caffeine, and when we’re kind of warming the planet and when we’re making those ocean waters much warmer than they usually are. It’s like an extra shot of caffeine in the coffee.”

And with ocean temperatures increasing — and reaching record highs in 2023 and into 2024 — it’s like giving hurricanes a shot of espresso.

Is this happening more often?

In 2023, rapid intensification joined the likes of polar vortex and atmospheric rivers as new weather terms in public vernacular.

First there was Hurricane Idalia in August that jumped from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in just 24 hours. It eventually hit the area of Big Bend, Fla., as a Category 3, causing widespread damage.

Then, two months later, Hurricane Otis stunned climate scientists.

Initially, when the tropical depression formed on Oct. 21 in the Pacific Ocean, forecasters had only called for it to develop into a tropical storm. Even in the subsequent days, the NHC had only forecast that Otis would be near hurricane strength at landfall and that heavy rainfall would be the main threat.

Well, here are the NHC’s maps at 1am Tuesday (1 day before landfall) and 1am Wednesday (landfall). At 1am Tuesday, there was no hurricane warning. There was a tropical storm warning and a hurricane watch. <a href=”https://t.co/wXKUazp6nI”>pic.twitter.com/wXKUazp6nI</a>

—@BMcNoldy

But then, the unthinkable happened.

On October 24, between 1 p.m. and 10 p.m. ET, Otis went from a Category 1 to a “catastrophic” Category 5, slamming into Acapulco and surrounding areas, killing at least 52 people.

Garner published a study in 2023 that looked at the increases in intensification of hurricanes in the Atlantic basin.

“I looked at a 50-year period. And one thing I found was that, we really can say that, yes, storms in the Atlantic have a tendency to potentially intensify more quickly than they used to.”

Her paper concluded that it has become more than twice as likely for a hurricane to develop from a Category 1 storm into a major hurricane — Category 3 and higher — in 24 hours or less compared to the 1970s and 1980s.

But that’s not to say that these types of hurricanes happen often.

“[It’s] still a rare event, but certainly more likely now than it would have been in decades past,” Garner said.

Can we forecast rapid intensification?

Forecasters were taken aback by Hurricane Otis in 2023. They couldn’t explain why the hurricane intensified so rapidly. But Garner said she anticipates research may help forecasters understand that in the future.

Still, as was seen with Hurricane Beryl, scientists did a better job of forecasting its intensification. On June 29, the NHC had forecast that it would “intensify quickly into a major hurricane.”

These early forecasts save lives.

After devastating parts of the southeast Caribbean, Hurricane Beryl churned toward Jamaica Tuesday as a monstrous storm. While the extent of the damage so far is unclear, authorities have said the picture on some islands is grim, with widespread destruction.

“It’s something that’s difficult to forecast, though we are getting better at it,” Garner said. “Messaging is one of the challenges and what my suggestion would be to anyone in a coastal community that might be threatened by a hurricane, is really heed those warnings, because forecasters really are doing their best to try to capture those potentially very quickly changing storms.”

Vecchi said that climate scientists are concerned about rapid intensification, because they don’t know if these types of hurricanes will always be difficult to forecast or whether over time forecasters will come up with better models to predict them.

Still, he said he’s hopeful.

“I am very optimistic that the tools, by the end of the season, will be probably better than the ones at the beginning of the season,” Vecchi said. “And next year will be better than this year.”