After successive failed asylum claims over the past six years, 35-year-old Ako has few options left. The UK government has offered the Kurdish-Iraqi two alternatives to staying in Britain: return to his home country or head to Rwanda voluntarily in exchange for £3,000.

Ali, meanwhile, says he has been given no such choice. Instead, the 23-year-old Eritrean has been informed he may be forcibly sent to Rwanda once flights begin to take off. “I am not sleeping. Sometimes I have bad thoughts, to harm myself.”

Ako and Ali are just two of the tens of thousands of people entangled in Britain’s asylum system, the rules of which have shifted several times over the past 14 years under seven home secretaries.

The scale of migration to the UK is among the top three issues exercising voters in the run-up to the UK’s general election, alongside health and the economy, according to YouGov polling.

Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer are both promising voters they will cut the number of asylum seekers entering the UK by small boats if their parties win on July 4. Arch-Brexiteer Nigel Farage’s return to frontline politics has pushed the hot-button topic further up the agenda, with his Reform UK party now threatening to take huge chunks out of the Tory vote.

If Labour sweeps to power as the polls predict, the party would have to pick up the pieces of a fragmented asylum system, including the Tory party’s flagship Rwanda scheme, while trying to make good on its pledge to reduce small boat crossings, increase returns of asylum seekers and end the use of asylum hotels.

But do Starmer’s policies stand any chance of reducing the number of people making the perilous journey across the channel, or are they just “fanciful”, as critics say? And will they make any difference to the lives of people like Ako and Ali, who find themselves trapped in the system once they are here?

Fixing the asylum system

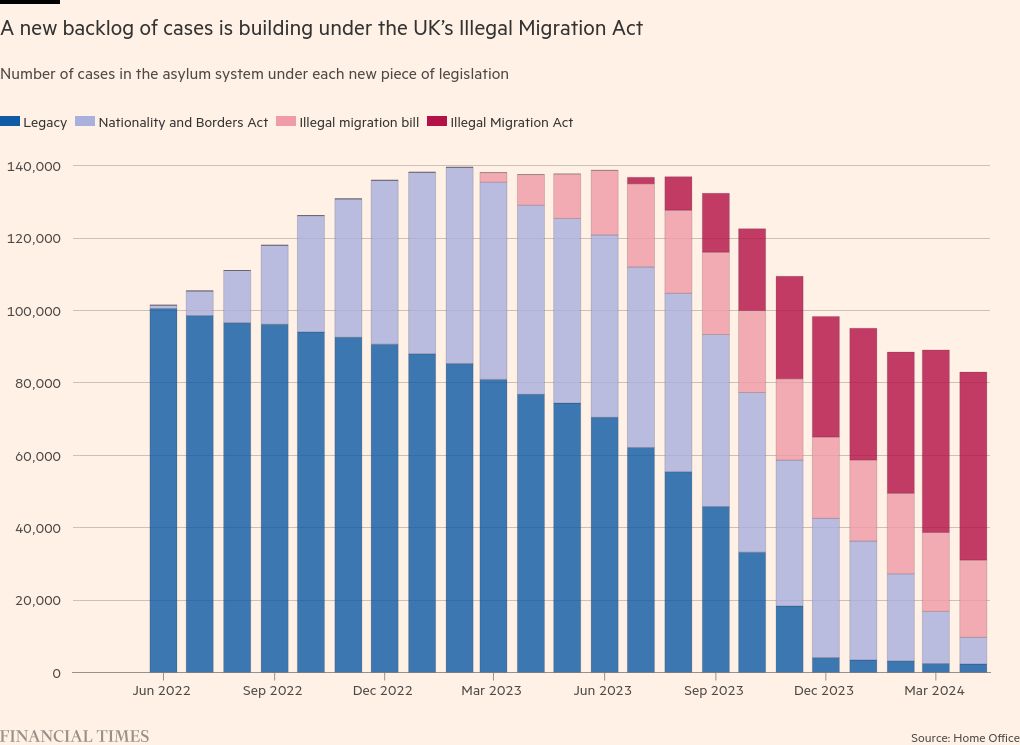

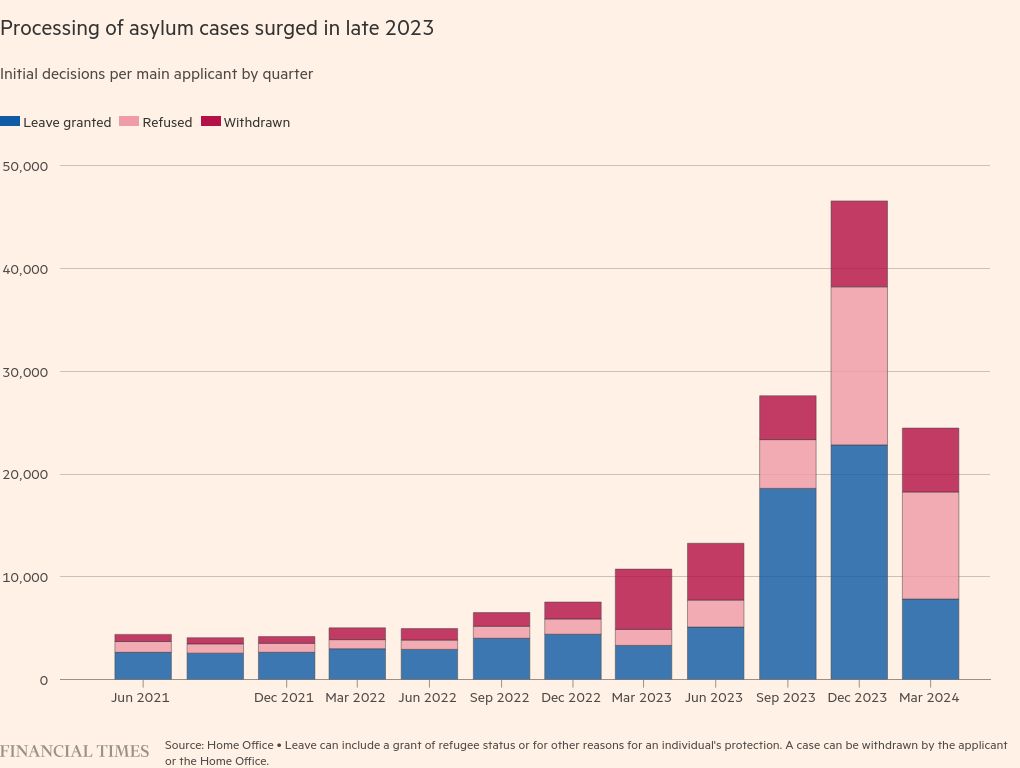

Sunak pledged to eliminate the so-called “legacy backlog” of asylum claims made before June 28 2022 by the end of last year, and, by hiring over a thousand new caseworkers and streamlining decision-making, he succeeded. The irony is that the government’s Rwanda scheme, which aims to send asylum seekers to the African nation to make their claim there, has created a new and growing backlog.

If Starmer steps into Number 10 on July 5, he has promised to process all historic cases.

Under the Illegal Migration Act, the legislation paving the way for the Rwanda scheme, it became unlawful to process the asylum claims of anyone arriving in the UK “illegally” after July 2023, making Britain’s one of the most restrictive asylum systems in the western world. There are now around 73,000 migrants stuck in the British asylum system with no legal avenue to remain.

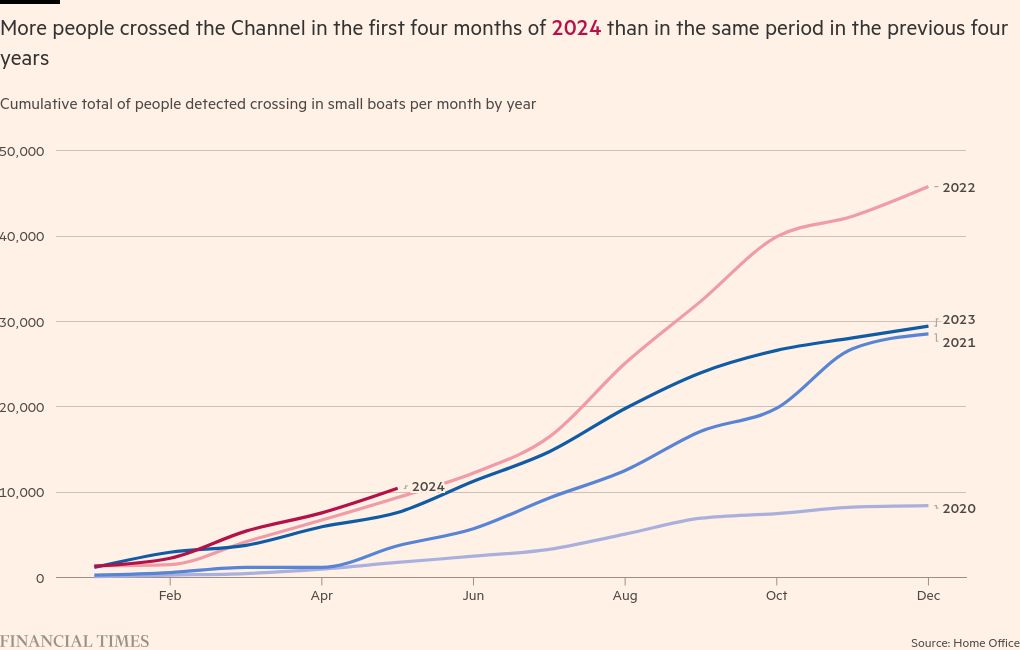

Yet channel crossings in 2024 are at a record high, undermining Sunak’s claims that his policies are already starting to act as a deterrent.

Starmer has committed to ditching the Rwanda scheme and insiders say Labour, if in power, will refer to this growing group of cases as the “Tory backlog”. The party says it will begin to reduce it by hiring an extra 1,000 caseworkers on top of the 2,400 already recruited.

But there is a further hidden backlog building — in asylum appeals.

The Tory government has slashed the rate at which asylum applications are granted, from an average of 72 per cent over the three years between 2021 and 2023, to 43 per cent in the first quarter of this year. This should have made it easier to generate a cohort of people suitable for return, but in reality it has led to a surge in appeals, which are more lengthy, complex and costly than initial decisions.

If Labour maintains this low grant rate, it could lead to an even bigger backlog of appeals. Party insiders say Labour has no plans to tinker with approval rates, but are adamant they will ramp up returns of failed asylum seekers.

But even before new arrivals were blocked from claiming asylum under the Illegal Migration Act, the UK’s acceptance rate was much lower than many comparable countries. In 2022, the UK granted around three positive asylum initial decisions for every 10,000 people in the population, compared with seven such grants across the EU27. Refugees and asylum-seekers made up 11 per cent of immigrants to the UK last year.

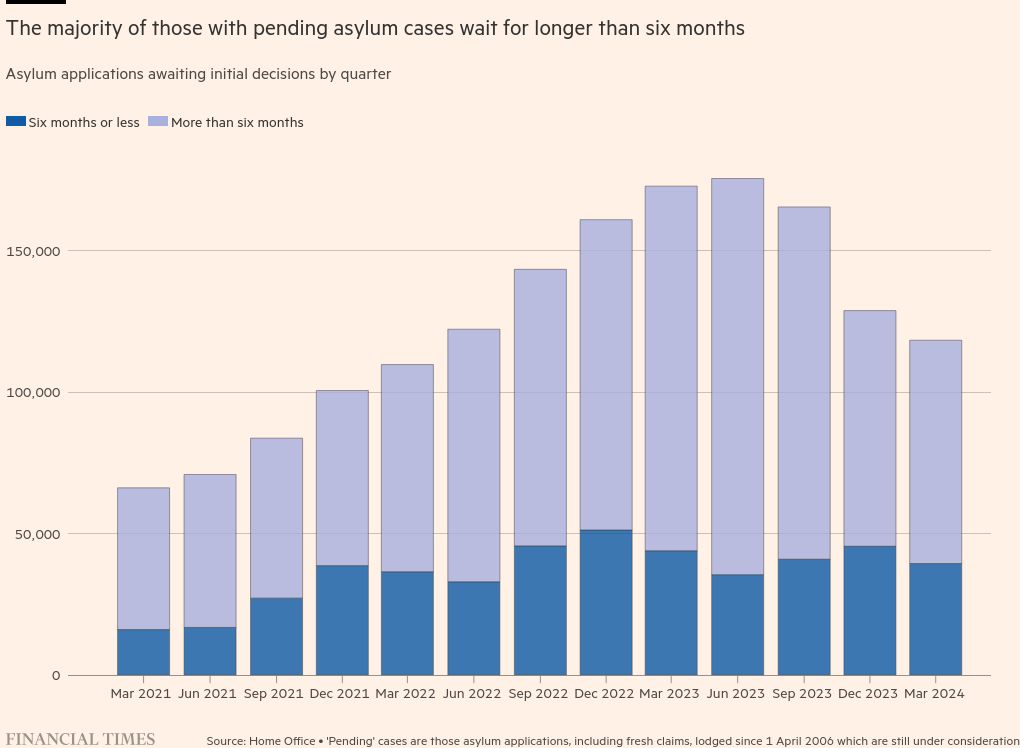

The UK’s low grant rate and slow-moving system places people’s lives in limbo for vast stretches of time, which can have a shattering impact on their mental health. Thousands wait more than six months and sometimes years for an initial decision, which permits them to stay in the UK temporarily as a refugee and work. Of the 118,329 people waiting for a decision at the end of March this year, 67 per cent per cent (78,901 people) had been waiting for more than six months. The Home Office does not publish data on how much longer than six months people wait.

Saeed, 27, who fled the conflict in Yemen, knows exactly how long he waited. “Two years, two months and 14 days,” he says without hesitation. But for him it felt much longer. Being moved from one asylum hotel to another, with no privacy and not knowing who to trust, he was in constant fear for his safety. He wanted to earn money and get on with his life, he says, instead of relying on others.

“The system is too slow. I am smart. I want to work. Let those waiting for asylum work. They can give back, they can pay tax,” he says.

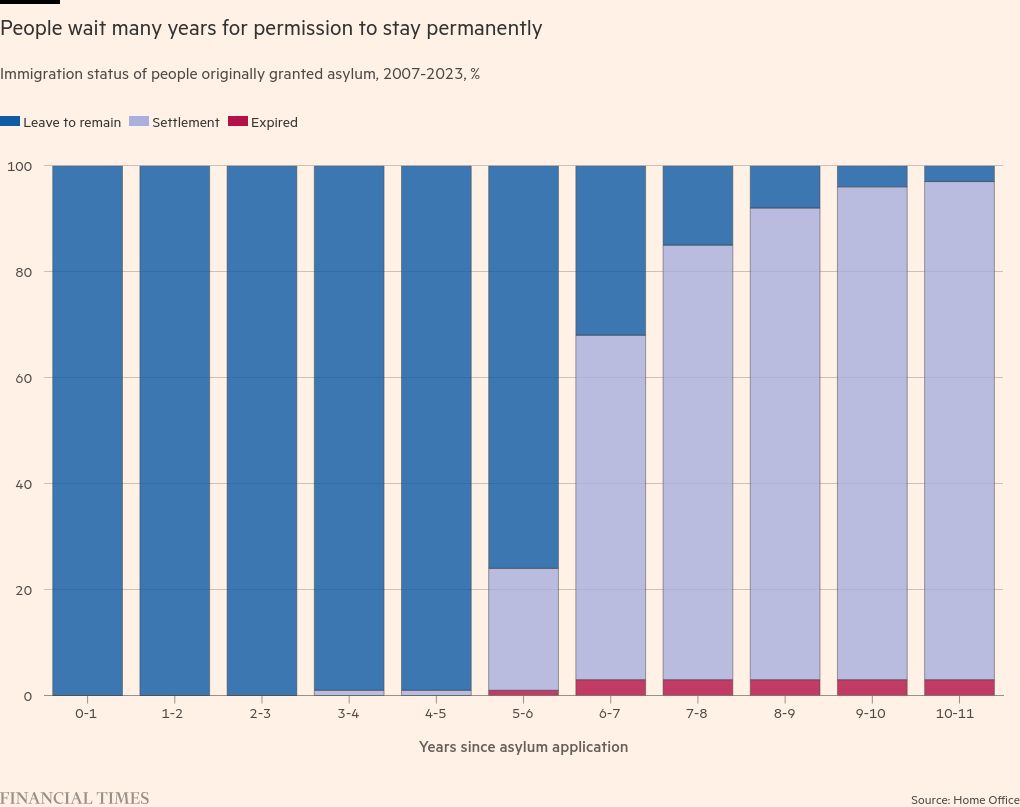

Those gaining temporary refugee status spend further years waiting for leave to remain in the UK indefinitely. Most wait longer than six years — some more than 10.

Can Labour return more asylum seekers?

Returns of migrants have plummeted. Migration experts say this is partly because it has become prohibitively expensive to transport people against their will overseas, with the government relying on costly charter arrangements after a backlash against the use of commercial flights.

Experts also say delays in the system have hampered returns because migrants build roots — find partners and have children — making it easier for them to challenge removals in the courts.

For Ako, from Iraq, the two options offered by the Home Office — to return home or head to Rwanda voluntarily — are impossible to take. “I have been living in this country for six-seven years. I have a child in this country. I have no idea about Rwanda, where Rwanda is.”

Another crucial problem is that the majority of refugees cannot be sent home safely nor to a third country, according to legal experts and refugee groups.

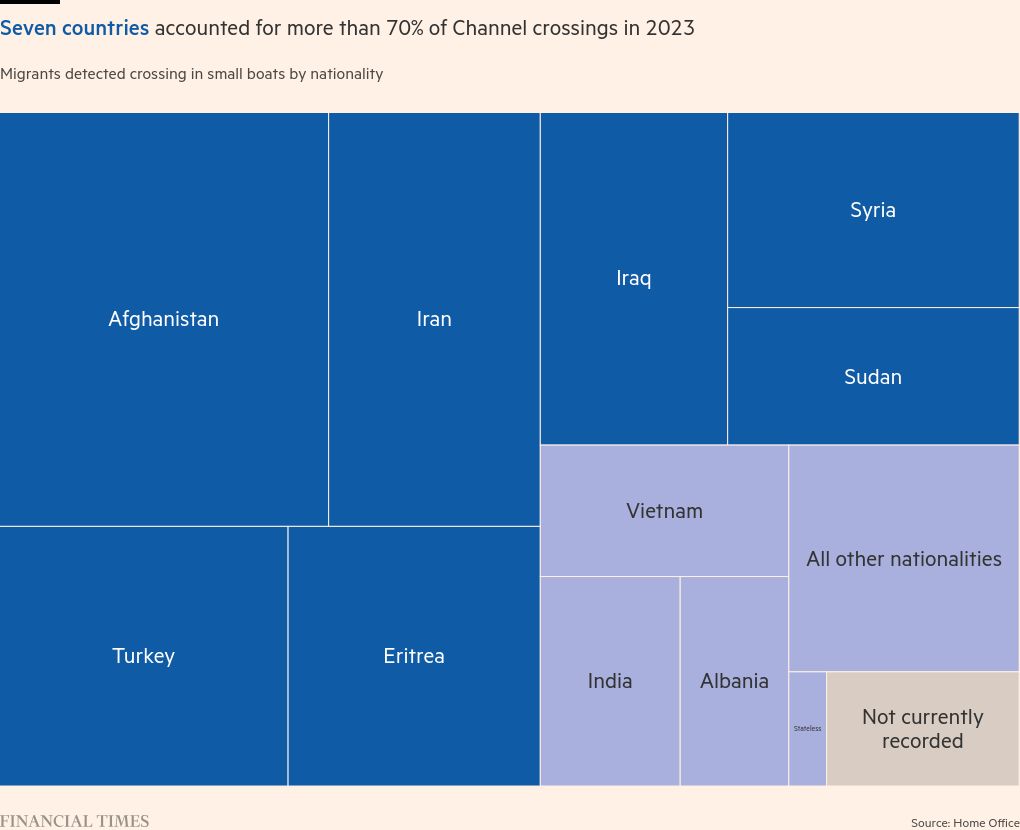

More than 70 per cent of the 29,437 people who crossed the Channel in small boats in 2023 came from just seven countries — Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Eritrea, Iraq, Syria and Sudan — none of which the Home Office regards as “safe”. Under international law, anyone seeking asylum cannot be returned to a country if it would jeopardise their safety. Speaking at a debate last week, Sunak derided Starmer’s returns plan, saying: “Will you sit down with the ayatollahs? Are you going to try to do a deal with the Taliban? It’s completely nonsensical.”

Labour says it will ramp up returns by hiring 1,000 more people to form a new Returns Unit that will rapidly review people who arrive from “safe” countries like Albania and India, so they can be swiftly sent back. The party has also said it will form bilateral returns agreements with countries not ravaged by war, like Vietnam, Turkey and Kurdistan, as well as forge a new returns deal with the EU. So far in 2024, Vietnamese migrants have topped the list of arrivals.

“Returns is resource-heavy work but it’s not impossible, we’re not chasing a pipe dream”, says one Labour insider, pointing out they have started to pick up since November under James Cleverly’s tenure as home secretary.

People briefed on Labour’s thinking say there is an opportunity to increase voluntary returns, which were at their highest rate for 15 years in 2023. These tend to involve offering migrants £3,000 to return to their country of origin, and are cheaper than enforced returns, which experts say cost in excess of £15,000 per person on average.

A Home Office official described Labour’s plan for returns as “fanciful thinking” as legal challenges make it an “absolute nightmare”. Labour’s critics also claim any returns agreement with the EU would entail receiving more — or at least the same number of — refugees from the bloc, making it redundant.

But one Labour insider says that the quid pro quo with Europe could be based on something different to raw numbers of asylum seekers, such as a potential deal on youth mobility.

Can Labour draw a line under asylum hotels?

Labour claims improvements in case processing and returns would have a transformative impact on one of the aspects of the asylum system the public feels most viscerally about: asylum hotels.

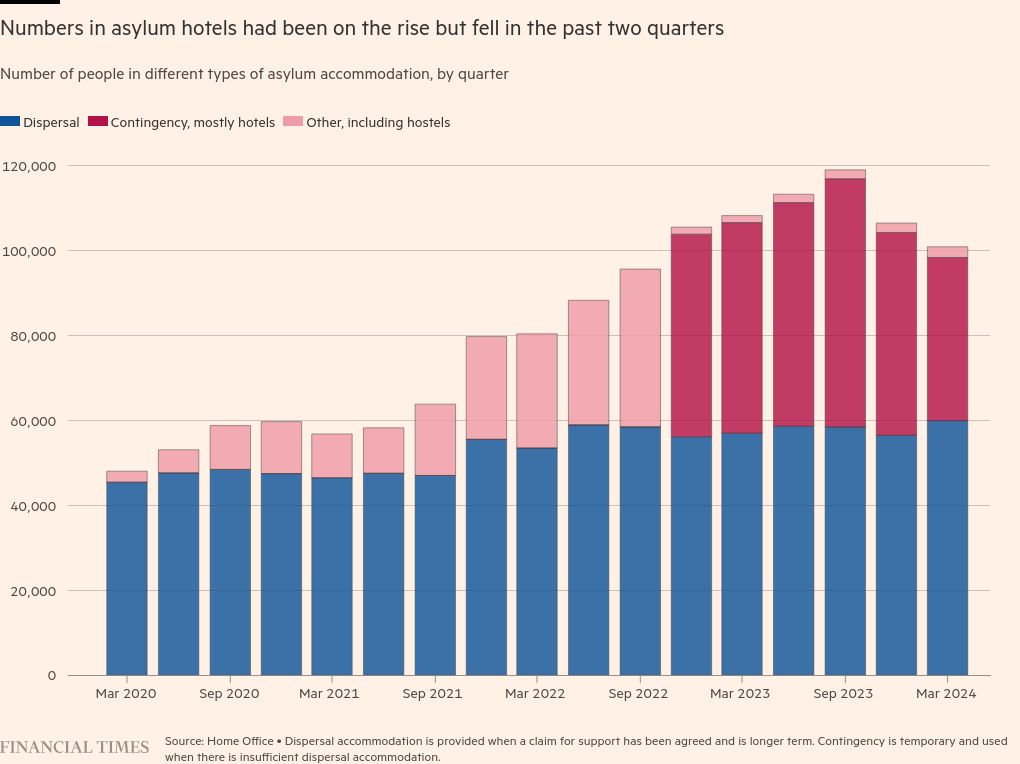

Most of the 73,000 migrants affected by the Illegal Migration Act are currently living in Home Office-funded accommodation — a mixture of long-term housing sourced by Home Office contractors, hotel rooms and large accommodation sites, including two converted RAF bases and a barge known as the Bibby Stockholm.

In some cases conditions in the housing are good. But in others, occupants describe inhumane environments, with a lack of security and privacy, and say the attitudes of some staff leave lasting scars. Women are particularly vulnerable, says Sam, 29, who fled the conflict in Sudan. One place she stayed in had such poor sanitation there was blood on the bed sheets. Fellow female asylum-seekers shared stories of sexual assaults, she says. “It’s horrible.”

The government has pledged to reduce the number of hotels and says it has closed 50 so far. But a recent public accounts committee report found the Home Office’s use of large sites, a key part of the strategy to stop using hotels, was a waste of taxpayers’ money as they would end up costing more and housed fewer people than originally claimed.

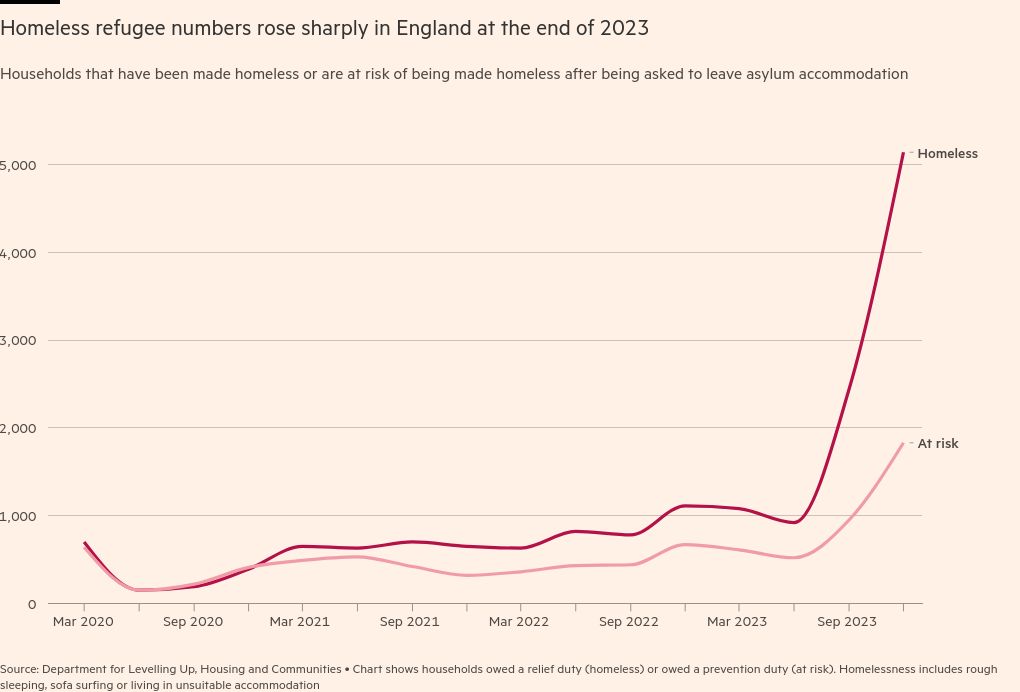

Ramping up processing and returns will be the key, Labour party insiders say, to their ambition to end the use of asylum hotels, large scale military sites and barges within a year of coming to power. They will instead rely on the roughly 60,000 spaces in government accommodation, currently managed by outsourcing firms such as Serco and Mears. But their plan could risk pushing higher numbers into homelessness.

The number of asylum seekers and refugees who have fallen into homelessness has surged over the past year. This is driven by a confluence of factors, including a rise in applications being “withdrawn” by the Home Office, an increase in application refusals, and the rapid rate at which asylum decisions are being made, with little support given to refugees once they are asked to leave government accommodation.

Saeed, from Yemen, said he was given three hours to vacate his accommodation after receiving a positive initial decision in his asylum case. He ended up sleeping rough at London’s Paddington Station for seven days before the charity Refugees at Home stepped in. “I was starving. I was scared,” he says.

Migrant charities want to see a new government extend the current 28-day “move-on” notice period given to those newly granted refugee status to 56 days, allowing them time to find alternative arrangements.

Enver Solomon, chief executive of the charity Refugee Council, described asylum hotels as “a graphic illustration of a system that hasn’t been working” and the large military sites as “ludicrous and ill-thought out”. He largely agrees with Labour’s approach. “If you had people flowing through the system fast, you wouldn’t need to have hotels at all.”

Can Labour drastically reduce small boat crossings?

The Tories insist the Rwanda scheme will act as a deterrent to boat crossings, pledging in their manifesto to remove illegal migrants to the African nation with “flights every month”.

Immigration lawyers and refugee groups claim that in reality Rwanda is only able to accommodate a few thousand asylum seekers, and that the focus on the ill-thought out policy has prevented the government improving other aspects of the system.

“You’ve only got so much bandwidth when you’re the government and they’ve been frittering it away with nonsense,” says Colin Yeo, a leading UK immigration barrister.

Labour’s plan to reduce boat crossings is to “smash the smuggling gangs” through a new Border Security Command, bringing together the National Crime Agency, the Border Force, Immigration Enforcement, the Crown Prosecution Service, and MI5. Insiders say Starmer is “incredibly passionate” about the policy, and wants his unit to work with overseas governments.

Tory insiders are scathing. “It’s just nonsense,” one says, pointing out the Conservatives are already targeting gangs. Another person, who until recently held a senior position in the Home Office, says: “It’s not going to work. The reason we have illegal immigration is not primarily because of gangs.”

Starmer has indicated he is open to an offshoring agreement with a third, safe country, where migrants could be processed overseas. However, unlike with the Rwanda scheme, successful asylum seekers could still be granted status in the UK. Labour insiders say any such scheme would have to be cost effective, have a credible deterrent effect and not break international law.

David Blunkett, home secretary under former UK prime minister Tony Blair and who looked into offshoring asylum seekers in 2002, says that such an agreement would only work if it was in concert with other European countries. “You can’t do it alone,” he adds. “If they can’t be returned home, all you’ve done is do the processing overseas and then you have to take them back anyway.”

He also cautions that the French election had “complicated things enormously” and Labour officials were “very concerned” about the impact of a far-right government on future negotiations.

Several refugee charities insist that if any future UK government is serious about reducing perilous channel crossings, it needs to create safe and legal routes.

But Starmer has said his party has no plan to do so. The party’s leadership also does not believe safe routes would materially reduce crossings, given large numbers are coming from places where there would be no asylum scheme, such as Vietnam, India and Albania, one party official said.

Solomon, from the Refugee Council, disagrees, pointing to thousands of refugees from Iran, Iraq, Syria and Sudan, who have no safe avenues to claim asylum from overseas. “You’ve got to address why people flee — the push and pull factors. There will have to be a recognition that there’s no magic bullet, there’s no point in overpromising and underdelivering by giving the impression there’s a quick fix to stop the boats.”

Blunkett says Labour, if elected, needs to take advantage of its first 12 months to enact its most radical policies, but also counselled against looking for quick-fix answers: “If it were easy, even this lot would have done it.”

Some names have been changed. Thanks to Refugees at Home, the Refugee Council, Refugee Women, Praxis.