Sheree Fertuck’s disappearance, the ensuing investigation and Greg Fertuck’s trial are the focus of the CBC podcast The Pit. Listen to all the episodes here.

Warning: this story contains distressing details.

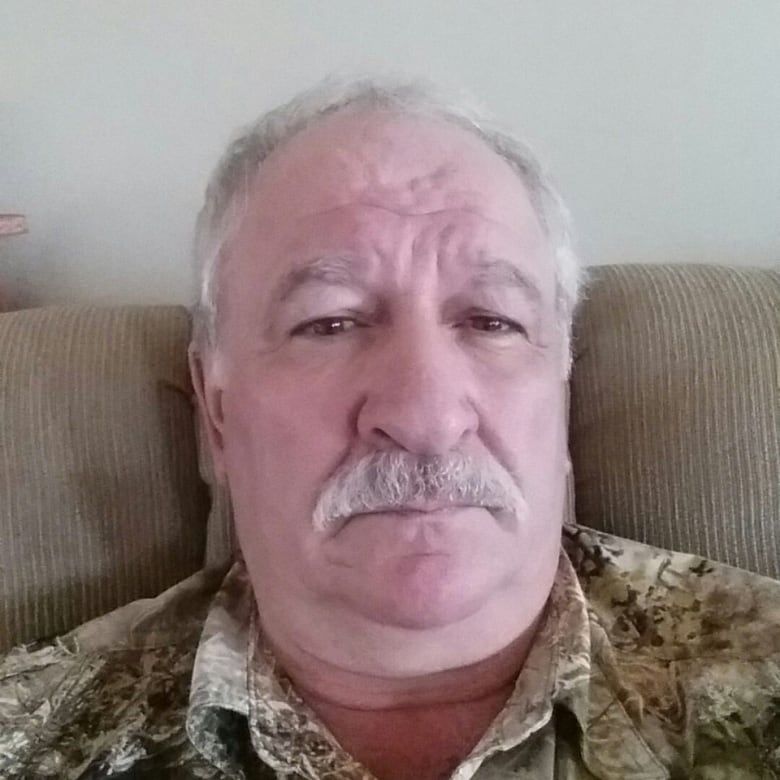

Greg Fertuck was the type of man who solved his problems through “intimidation, threats and violence.”

Evidence at his murder trial showed he had to have his way — or else.

“When [his wife Sheree] would not comply by his own admission he went to his truck, got his rifle, shot her in the shoulder, then coldly shot her in the head. He killed her in cold blood,” wrote Justice Richard Danyliuk in his trial decision.

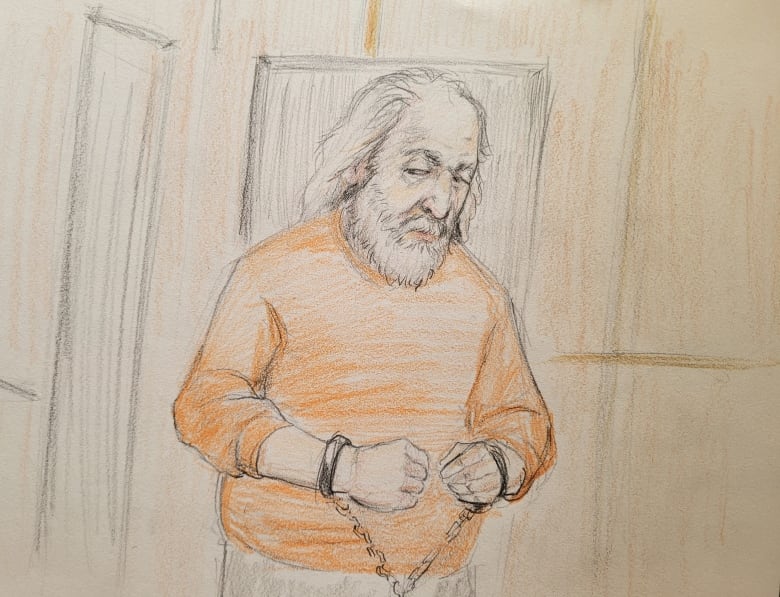

Danyliuk found Greg guilty of first-degree murder on June 14, 2024, after a lengthy and complicated trial at Saskatoon’s Court of King’s Bench.

Greg was also found guilty of indecently interfering with Sheree’s remains because he hid her body in a secluded area near some poplar trees after the murder. Her remains have never been found.

Justice Danyliuk wrote about how this denied Sheree’s loved ones the chance to say a proper goodbye.

”Greg once said he loved Sheree. They built a life together. They had three children together. While it all fell apart, to try to solve financial and personal issues through the most extreme form of violence and then unthinkingly dispose of Sheree as if she was a nuisance is a form of spousal abuse. It is the highest form of such abuse.”

Sheree’s death was a preventable tragedy, according to Jo-Anne Dusel, a provincial expert on abuse in relationships and intimate partner homicide.

Other innocent women will suffer the same fate unless changes are made, Dusel said.

Sheree was 51 when Greg killed her. She has been described as a tough woman and devoted mother of three who loved her dog, her family and her work — hauling crushed rock from a rural gravel pit near Kenaston, Sask.

“She was an absolutely 100 per cent loyal friend. She would do anything for you if it was within her power to do. She was so full of life and fun to be around,” said her friend, Heather Mitchell.

“People just need to understand that this is just so unfair what happened to her. It was just absolutely devastating.”

The murder was Greg’s final act of cruelty toward Sheree, but it was far from the first.

A history of violence

Greg abused Sheree for years before he killed her.

Court evidence showed he was a mean man who insulted Sheree constantly. Verbal abuse escalated to physical abuse and death threats.

Before Greg and Sheree separated, he was twice convicted of abusing her.

In November 2010, Greg pleaded guilty to uttering a death threat against Sheree and possessing a prohibited weapon. He had threatened to shoot Sheree between the eyes.

Greg participated in a domestic violence treatment court option, which meant he underwent rehabilitative counselling in exchange for a reduced sentence.

The judge dismissed the prosecutor’s request for a five-year firearms ban and, during sentencing in April 2011, described Greg as someone who had been a “successful person in the community for quite a long time.”

It wasn’t long before Greg was back in court for assaulting Sheree. He had grabbed Sheree by the head and neck — dragging her out of a room during an argument.

When police went to their home, they found Greg had more prohibited guns — including an illegal machine gun and other unregistered rifles and magazines.

The Crown argued Greg should face a year in jail and a lifetime weapons ban, but the judge who ruled on the matter said that, compared to the kinds of assaults she routinely heard about in court, what Fertuck had done was at the “low end.” He was given a six-month sentence in the community.

That was about three-and-a-half years before Greg killed Sheree.

Jo-Anne Dusel said that when an abuser is allowed to escalate their behaviour with few consequences, they become emboldened.

“If Sheree had come to me back in the day when I was a shelter worker and told me her story, I would have been extremely concerned for her,” said Dusel, who worked on the front line for 20 years and now leads the Provincial Association of Transition Houses of Saskatchewan.

“I would have suggested that she probably relocate for her own safety if there was not some sort of criminal or legal remedy to keep him as far away from her as possible.”

Instead, Sheree kept Greg close.

The catalyst

As the end of 2015 approached, Sheree and Greg were still struggling to work out the terms of their divorce. Tension was brewing.

Sheree didn’t believe they should split their assets down the middle. She wanted to make sure their kids were looked after and Greg owed Sheree more than $25,000 in unpaid child support.

However, Sheree told her family lawyer that she wanted to work things out with Greg directly because she was concerned about costs.

During this time, Greg was struggling financially with outstanding debt and accounts in overdraft. He wanted to access a lump sum of money from a locked-in retirement account, but required his wife’s permission to do so.

She denied his requests.

As this dispute simmered, Greg was working some shifts for Sheree at the gravel pit.

She was wrapping up for the season just before the murder. Greg was licensed to drive a semi, and knew the area and equipment well.

The working arrangement turned sour when Sheree discovered Greg was claiming more hours than he had worked.

Sheree’s mom, Juliann, had already written him a cheque for that time. Sheree wanted to cancel the payment.

Sheree called the bank on the morning of Dec. 7, 2015.

She also called Greg.

The killing

For years, Greg denied killing Sheree. He likely would have gotten away with it, had he not confessed the details to multiple undercover police officers at the conclusion of a months-long, elaborate sting operation.

Greg told undercover officers he drove to the pit, parked his truck where Sheree could not see it and surprised her after her routine lunch break.

He said he wanted to talk to Sheree about money and their property. He became unhappy with the conversation’s direction, so he walked back to his truck and grabbed his unregistered semi-automatic rifle, shot her in the shoulder, then shot her in the back of the head.

Dusel said Sheree’s decision to hold Greg accountable was a dangerous move given his abusive tendencies.

“Often when a situation like this — where there’s an ongoing pattern of abuse — is going to trigger a shift into more serious violence, femicide, there is a catalyst. And in this case, it appears to me that the catalyst was that financial situation.”

Dusel wonders if Sheree would still be alive had the justice system prepared her for the possibility that Greg would go through with his threats.

She said the risk factors in Sheree’s situation were clear: the tumultuous separation, Greg’s patterns of threats and abuse, the police reports and his guilty pleas, Sheree and others being afraid, Greg’s breach of court conditions and his unregistered guns, to name a few.

However, Dusel said it doesn’t appear that these risk factors were assessed as a whole or acted upon.

“Unfortunately in our current legal system, it’s set up based on individual incidents and very seldom do all the pieces come together in terms of determinations that are being made for the safety of victims.”

Sheree Fertuck, a 51-year-old mother of three, vanished on Dec. 7, 2015. More than eight years later, a King’s Bench judge has found Sheree’s estranged husband guilty of first-degree murder, despite her body never being found. The host of CBC’s podcast The Pit, Kendall Latimer, lays out the twists and turns of the case.

Many people — family members, police officers, family law workers — knew bits and pieces of how Greg abused Sheree, but they were never brought together to connect the dots.

Other provinces have law enforcement teams dedicated to working on high-risk intimate partner violence cases, Dusel said.

“One of the things that happens in other jurisdictions, that we don’t do here, is to have information-sharing agreements among different government systems and [advocates],” Dusel said.

“I can point at Alberta and B.C. that both have teams that deal with high-risk situations where all of the information is on the table and then risk management takes place.”

That risk management can involve a more stringent follow up with perpetrators after the court process, Dusel said. It could also include helping victims make safety plans and understand what might trigger the perpetrator — like a fight over finances.

“If the players were to come together to look at these risks and our legal system was actually responding in a way that was putting the safety of women first —I think there could have been a different outcome in [Sheree’s] case and in others like it.”

A Saskatchewan problem

Sheree’s story is unique, but shares unfortunate details with others.

“It’s no secret that Saskatchewan has the highest rate of police-reported intimate partner violence among the provinces in Canada,” Dusel said. “Saskatchewan also has the highest per capita rate of intimate partner homicides.”

There are many factors that contribute to the high rates of abuse, including the gun culture and the prevalence of rural communities, which can lack services and confidentiality. Boom-and-bust economies go hand-in-hand with violence, Dusel said, as it often increases when financial stress rises.

But there’s an attitude problem at the heart of it all.

“We need to make sure that young people don’t grow up with attitudes that diminish women. I think we need to support boys and young men in being emotionally healthy.”

She said there are deeply ingrained beliefs of misogyny, traditional gender roles and disrespect toward women in this province.

It’s a place where sexist or vulgar slogans, jokes and remarks are normalized. Dusel said these attitudes pave the path toward more serious violence against women.

Greg Fertuck was no exception.

When dark thoughts become dark deeds

Justice Danyliuk’s decision was a meticulous and thorough journey through evidence, but also through Greg’s character.

“Greg did have a dark side. He was a misogynist, regarding women as ‘only good for one thing.’ He clearly saw women as inferior. He clearly believed women should obey men. His comments about women with the undercover operatives were beyond rude; they were vulgar and often disgusting. He harboured violent thoughts.”

Not only did Greg berate, belittle, threaten and beat Sheree, he also was abusive toward his children and other romantic partners.

“A person’s view of gender relations certainly does not make him a murderer. However, Greg’s thoughts turned into deeds.”

When Greg ended Sheree’s life, he also created ripples of pain in the lives of many others.

Sheree’s friend, Heather Mitchell, has been trying her best to keep Sheree alive in her memories by holding onto their good times.

“I don’t like to think about her as a murder victim. That hurts when I think like that.”

Mitchell also thinks a lot about the moments and milestones Sheree has missed — including the chance to witness her family grow.

“I think mostly about the children and the grandbabies, and I’m just praying that somehow, some way, they can get beyond this and move on, but never, ever, forgetting who their mom was and how much she loved them,” Mitchell said.

Greg Fertuck’s sentencing hearing is scheduled in Saskatoon for July 4. He faces an automatic life-sentence in prison for the first-degree murder conviction.

“Justice has finally been served,” said Sheree’s sister Glenda Sorotski.

“We weren’t able to give a proper send off and say a proper goodbye to Sheree, but this is some sort of closure for us and we just firmly believe that Sheree can now rest in peace.”