Good afternoon. After a couple of weeks away doing election coverage, I’m back and will be with you right through the first few weeks of the new government.

This time next week, the British electorate will be queueing at the polling stations to pass its verdict on 14 years of Tory party rule. Assuming we haven’t had the largest polling upset in history, that will also be the last day in which Labour politicians will be able to fail to answer questions without incurring mounting political costs.

During the campaign, the party has largely had a free pass. That’s down to a combination of deep public animus towards the ruling party and a tacit sense that Labour’s plans for the country — however hazy — must be an improvement on the Johnson-Truss years.

But the questions about what is going to happen next will crowd in pretty quickly once the new cabinet is sworn in.

Having read the entire Labour manifesto (don’t mention it, the pleasure was all mine), it’s striking how the policy programme is split between small-bore offers to the electorate on the NHS and schools and sweeping, long-term “supply side” measures such as planning reform, devolution and regulatory improvements which — while essential — will take time to bear fruit.

So, to recap the manifesto, there’s a . . . deep breath . . . :

Strategic Defence Review; a Covid Corruption Commissioner; a Universal Credit review; a Teacher Training Entitlement & School Support Staff Negotiating Body; an Industrial Strategy Council; a National Data Library; an NHS Innovation and Adoption Strategy; a Regulatory Innovation Office; an Independent Ethics and Integrity Commission; a Council of Nations and Regions; a National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority; a Police Efficiency and Collaboration Programme and an Expanded Fraud Strategy, to name but a few.

You get the picture. Concealed in that forest of capital letters are lots of good ideas such as the Regulatory Innovation Office, which should enhance the enabling function of regulators, as opposed to the purely watchdog side of their remit. That should, in time, be good for growth and attracting investment.

But, equally, there’s clearly a certain amount of deliberate obfuscation. The promised “review” of universal credit might be a way of kicking hard decisions into the long grass, or it could be code for removing the two-child cap on benefits. The electorate hasn’t been told.

The cap is a huge driver of the UK’s very poor record on child poverty, but fixing it would cost £3.4bn, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies — that’s the same as freezing fuel duties for the next parliament. It will soon be time to choose: one person’s “investing in the future of our children” is another’s “war on motorists”.

Similarly, on higher education. The manifesto says, quite bluntly, that the system is “in crisis” — which clearly implies that Labour must do something — but then provides zero information about how a Labour government intends to address the problem it has correctly identified.

Is the party prepared to put up the £9,250 tuition fee, which has been frozen for a decade? Or even let it increase in line with inflation — both of which have short-term implications for government outlay on student loans — or will it increase direct funding to universities? Or none of the above.

Doing nothing is not an option

It cannot do nothing. One well-connected former vice-chancellor posits a three-step approach: an immediate fee increase to £9,750; moves to reduce regulatory burdens on universities, and then another quick-fire “review” of the student loan repayment system to ease the burden on poorer students and lower-earning graduates.

“Let me be clear that reform is coming,” shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson said in a speech to the Universities UK conference in September last year, citing what she called “desperately unfair” changes to the student loan repayment system that landed harder on women and lower earners.

So we know something is coming. And very soon that “shadow” will be removed, and Phillipson, as education secretary, will go from making speeches to actually battling with the Treasury and Downing Street over implementing reforms that might cost money or risk causing political ruffles.

The most radical step — contemplated in some Labour circles — would be to introduce a form of “stepped repayments” that would see higher earners paying a lot more over their earning lifetimes than they borrowed — perhaps double the amount, according to illustrative modelling by London Economics.

That could be wildly unpopular — polls suggest most people don’t think it’s fair to pay more than they borrowed — and beg big questions about using the student loan system as a wealth redistribution mechanism, but to govern is to choose.

After 14 years in opposition — and 14 years in which the ruling party has largely been distracted by having a war with itself — this new era of choice-making should be an exciting prospect for Labour. But it is going to require a step change in approach from carrying the oft-mentioned “Ming vase” across the marble floor of the recent election campaign.

And even more than usual, given the deliberate vacuity of much of Labour’s policy platform, stepping across the threshold into government is, I suspect, going to be a shock.

It will not be aided by the fact that Rishi Sunak’s early election call meant the Labour decision-making machine was distracted by the instant campaign before some of the big decisions could be ironed out.

Or the fact that Labour’s most ambitious policies are those “supply side” reforms — fixing planning, deepening devolution, re-engaging with Europe — that will bear fruit on a different timeframe to the impending short-term departmental spending squeeze.

Labour will have to stay the course on its “big ideas” while trying to emphasise the value of what are essentially pop-gun policies: such as the 2mn extra hospital appointments in England that are equivalent to 2 per cent of the annual total; or a teaching recruitment drive for 6,500 teachers that amounts to one new teacher for every three state schools.

Without money to throw at the problems that daily confront a dispirited electorate, it is going to take considerable political skill on the part of the Labour leadership to keep up a sense of momentum that change is possible — and, ultimately, keep the country on board.

Would you like UK election updates straight to your phone? The FT has a WhatsApp channel dedicated to our UK political coverage. Subscribe here and receive one story a day.

And don’t miss our election webinar unpacking the results on July 5. Stephen Bush, author of the Inside Politics newsletter, will be joined by Political Fix podcast host Lucy Fisher, political editor George Parker, and columnists Robert Shrimsley and Miranda Green (register here to join the Q&A for free).

Britain in numbers

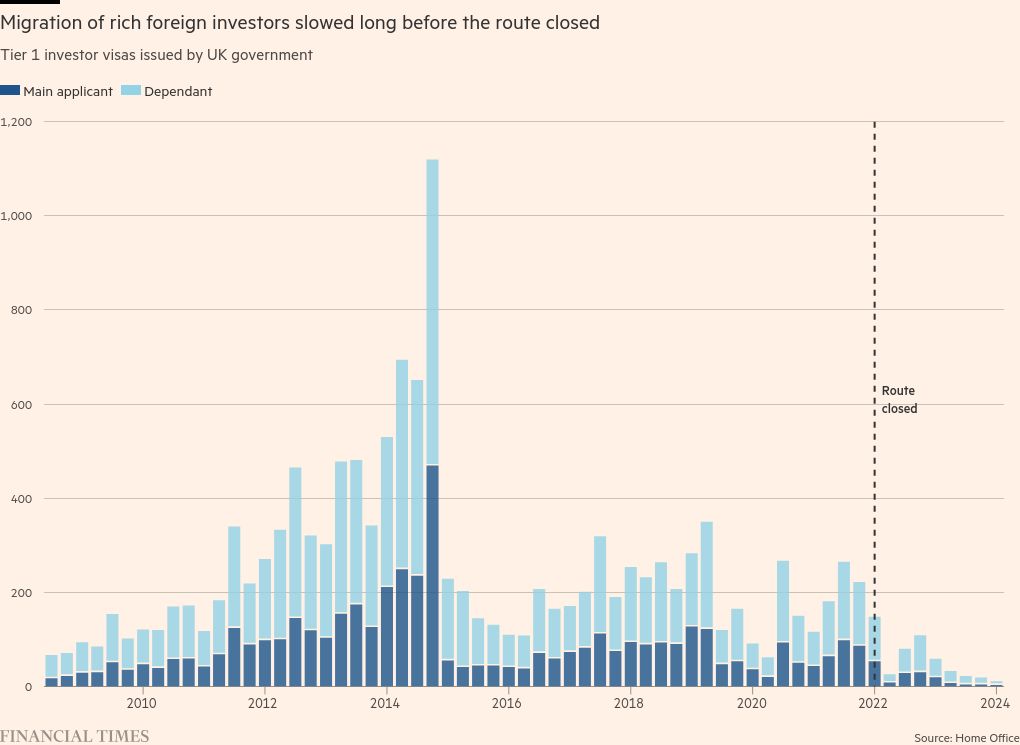

This week’s chart comes from the latest Home Office visa statistics, which show that the UK lost its appeal to rich foreigners long before the overhaul of “non-dom” status was announced, Amy Borrett writes.

Jeremy Hunt revealed in his March budget that wealthy foreigners will be forced to pay tax on overseas income from April 2025, with Labour threatening an even tougher regime if elected on July 4.

The move is expected to cause an exodus of ultra-wealthy individuals who think the UK is no longer an attractive place to live and fear further punitive tax changes under a future Labour government.

But Home Office data reveals that Britain has struggled to attract foreign millionaires for almost a decade.

Since 2015, fewer than 400 investors have arrived each year on a Tier 1 investor visa — a scheme introduced in 2008 to attract millionaires with the promise of expedited British citizenship.

This is a precipitous decline from the peak of almost 1,200 in 2014 when there was a rush of applications after the Home Office announced plans to double the investment threshold to £2mn following a review by the Migration Advisory Committee. It found that Tier 1 investor visas offered little economic benefit.

Before the route officially closed in February 2022, even tighter restrictions, Brexit and growing concerns over street crime damped demand for the visa, according to consultants who advise millionaires about migration.

The UK is not the only country closing its doors to the ultra-wealthy. Spain, Portugal and Ireland have all scrapped property investor visas in recent years over concerns about security, corruption and money laundering.

But despite the crackdown in some countries, demand for golden visas remains high, with wealth migration forecast to rise a further 15 per cent this year.