Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Few data points create as much excitement in markets as America’s non-farm payrolls. As a vital indicator of the health of the US economy, it features heavily in the Fed and investors’ assessments of the future path of interest rates.

But, it may be dodgy. When the numbers — showing a still red-hot labour market, churning out jobs — do not match the economics, high interest rates, low SME hiring plans, and weakening growth momentum, it is always worth digging for any potential data quirks. (Alphaville has already touched on how a significant share of US job creation has been driven by the health and social care sector).

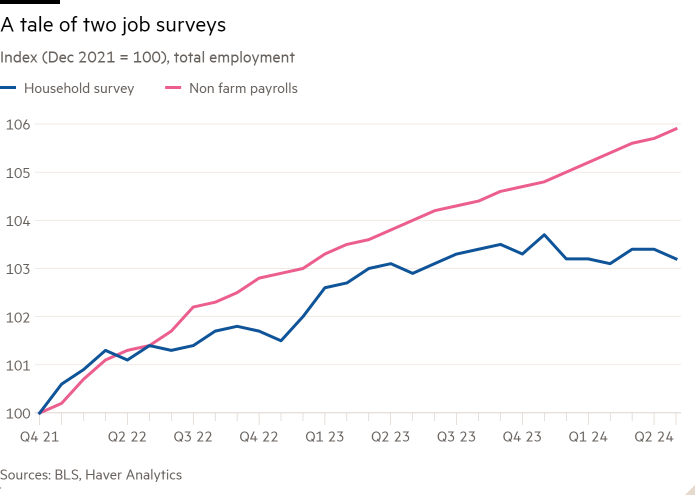

What’s happening? America’s non-farm payroll numbers, via the Establishment Survey, suggest relentless job creation — it reported 272k new jobs in May. The Household Survey data implies employment is slowly trending down, last month it registered a 408k drop.

Both surveys have different samples and scopes so differences are to be expected, the problem is that their current trajectories tell different stories.

So what are the main differences between the surveys?

The establishment survey samples over 650k employers. The household survey samples 60k households. Multiple job holders are counted multiple times in the establishment survey, but just once in the household survey, which also includes the agriculture sector.

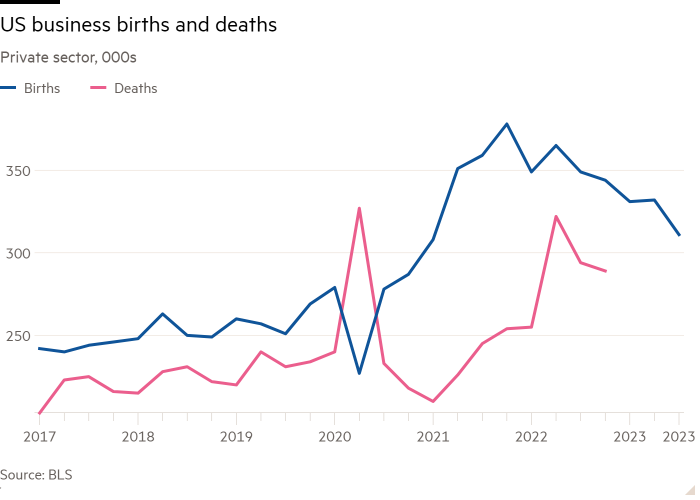

Due to their different samples, each relies on different models to aggregate-up to an estimate for the country. The establishment survey does this via estimates of business births and deaths data. The household one bases it on population projections.

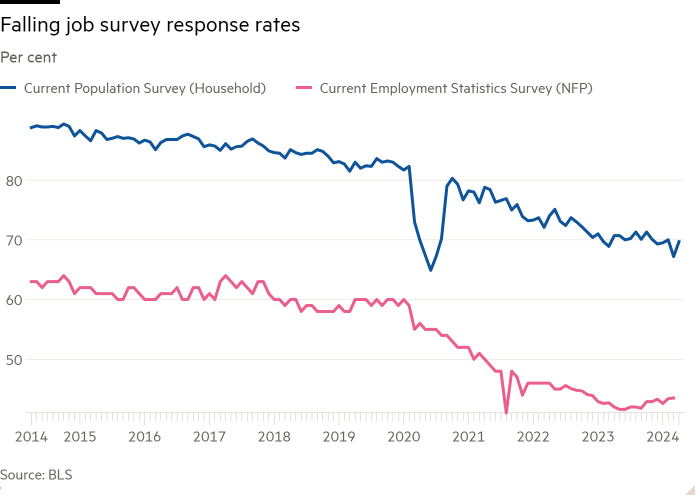

In Britain, there is plenty of focus on the response rate for its Labour Force Survey. But America has similar problems. Response rates for the establishment survey in particular have dropped markedly since the pandemic. As a starting point, that may be impacting its accuracy somewhat.

Essentially, then, there are four sources for the difference:

1. Bias in the base sample

2. Definitional variations

3. Errors in scaling-up the household survey, based on population estimates

4. Errors in scaling-up the established survey, based on business birth/death estimates

The first is difficult to quantify. But we can assess the rest.

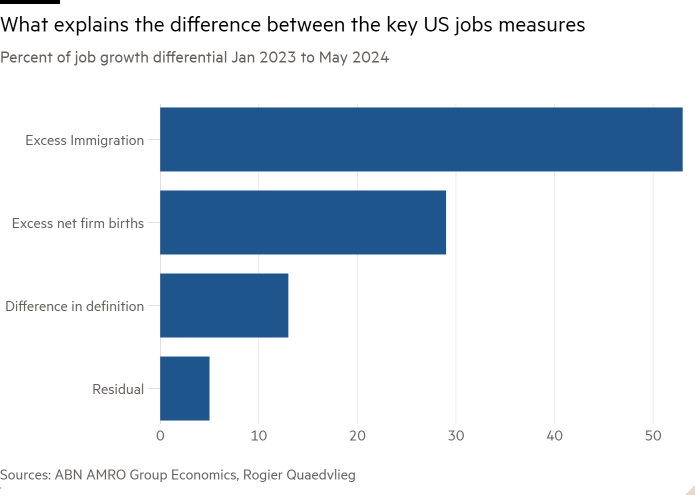

Rogier Quaedvlieg, a senior economist at ABN Amro, has done a deep dive into the US “labour market puzzle”. On the second, correcting for differences in definitions, he finds that “the levels of the two series largely line up until 2022, but . . . have diverged since.”

Now for three and four. Aggregating-up to population and business population has been particularly challenging post-pandemic.

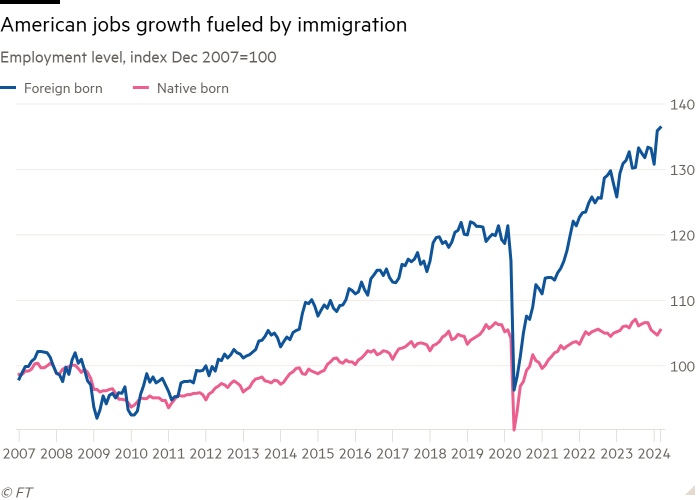

It is possible that the household survey has been unable to fully account for the large inflow of foreign workers into the US in recent years (which may have been easier to capture in employer surveys for the NFP). Higher estimates of immigration bridge a considerable amount of the remaining difference between the two series, according to Quaedvlieg.

Next, estimating the birth/death rate of businesses — and thus the impact on employment — has been harder post-pandemic due partly to changes in working styles and the rise of new business models. The BLS has assumed a higher net birth rate relative to pre-pandemic.

“If we rather assume a similar rate to the pre-pandemic period — a conservative assumption given the recent rise in bankruptcy filings — job growth is adjusted downwards” adds Quaedvlieg.

Totting it all up, ABN Amro finds that the gap between the two series is driven largely by underestimating immigration, and overestimating business births, and then definitions.

The upshot is that we can perhaps expect hefty revisions to the US employment data — as we have become used to — when the actual population and business population data come in (they lag considerably, which is why the BLS needs to make the forecasts).

The conclusion? The labour market is probably softer than the non-farm payrolls are conveying, but perhaps not as weak as the household survey is showing either. The Fed and markets may want to look at other economic data points more closely for clues on the jobs market, including jobless claims, hiring surveys, and the (rising) unemployment rate (where the above population issues should effectively cancel out).

And, with news earlier this month that the BLS will need to cut sample sizes in light of budget constraints, the next occupant of the White House should probably think about doing more to support the nation’s most vital statistics.