Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As votes from India’s six-week long general election were counted on Tuesday, it was quickly clear that Narendra Modi was on course for his third term as prime minister. That is where his satisfaction will end.

The early results also showed Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party set to lose its majority for the first time since 2014 — a stunning blow to the authority of India’s strongest leader in decades and one that would leave him dependent on junior partners in his National Democratic Alliance to govern.

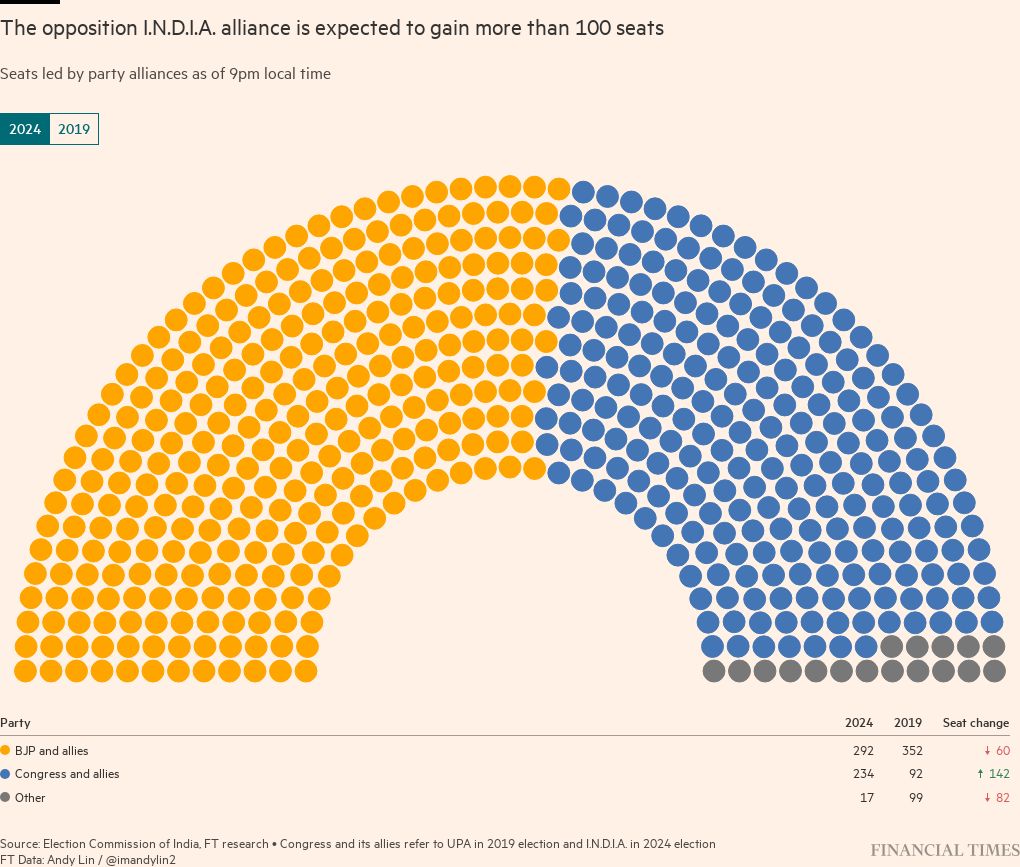

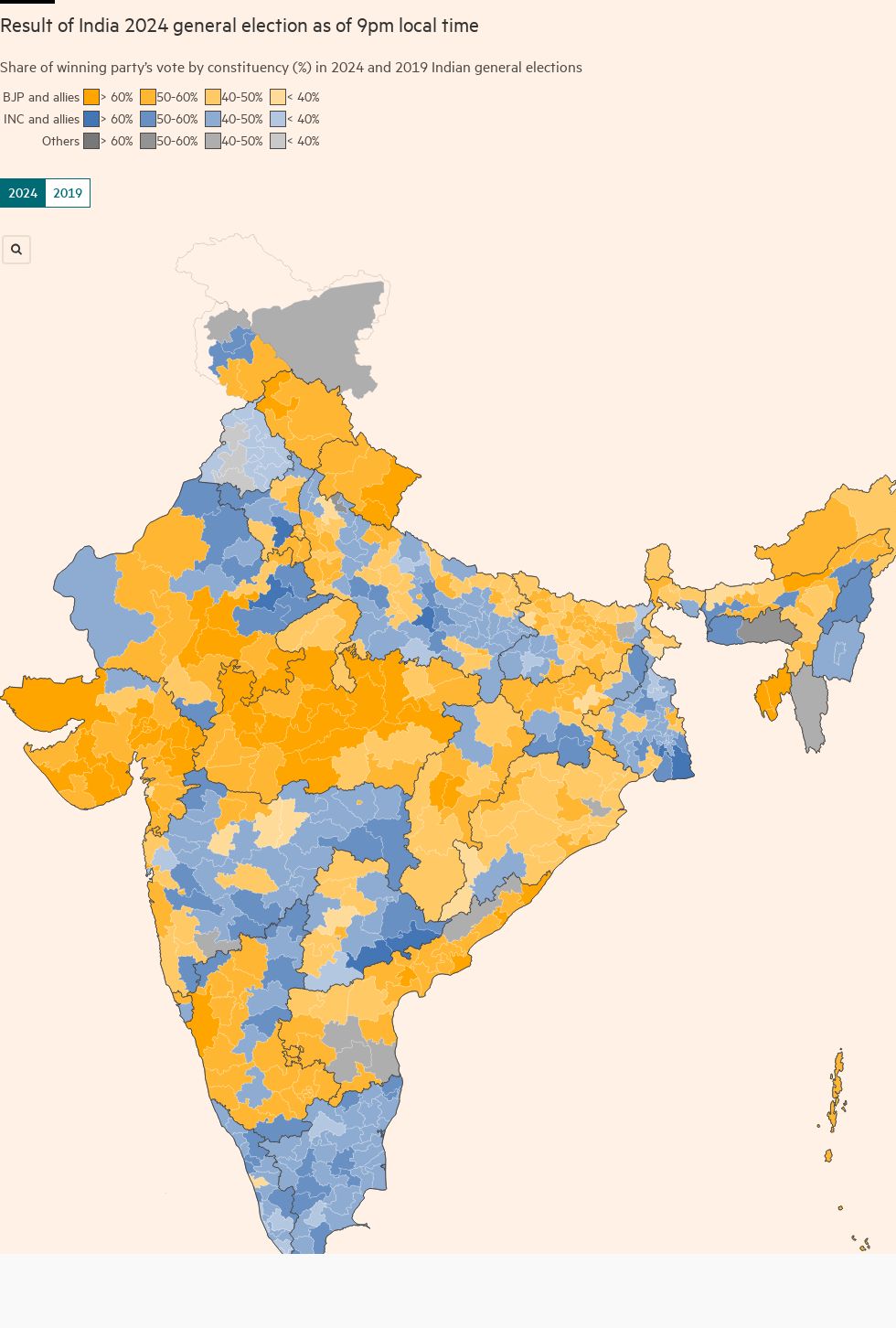

On Tuesday night, the NDA was ahead in 291 of 543 seats in India’s lower house of parliament, far below the more than 350 it held before the vote and the 400 that Modi had set as its target. A motley coalition of anti-BJP opposition parties, known by its acronym INDIA, was on track to nearly double its tally to 234.

Confirmation of the shock result would leave Modi in a weakened position from which to tackle the enormous economic challenges facing India and to undertake the difficult reforms needed to help the world’s most populous country secure its status as a rising global power.

Modi had lost his “aura of invincibility”, said Ronojoy Sen, a political scientist at the National University of Singapore.

“The knives won’t be out but . . . Modi’s standing within and outside the party [could] take a beating,” he said, adding that the BJP’s coalition partners would “take their pound of flesh”.

Before the results, Modi’s government had exuded confidence. At his final campaign rally last week, the prime minister crowed prematurely about scoring a “hat trick” of absolute majorities in three successive elections. Exit polls published at the weekend also predicted a resounding victory.

Modi brushed off concerns about the result on Tuesday night. “Our opponents together have not won as many seats as the BJP alone has won,” he told a crowd of supporters, referring to the roughly 240 seats where the ruling party was in the lead in partial counts. “The country will write a new chapter with many big decisions in the third term.”

International banks and investors, who have placed bets on India as a pivotal “China plus one” economy and growing consumer market, will be keenly watching how durable a coalition government Modi can build.

Modi has sold himself to both the Indian public and overseas investors as a strong, decisive leader capable of enacting tough reform and maintaining stable government. But analysts warned that reliance on its NDA partners, which include several smaller regional parties, could force the BJP into concessions such as offering them ministerial posts and dropping politically unpopular reforms.

The early results triggered a sharp sell-off in Indian equities on Tuesday, with the benchmark Nifty 50 stock index falling 6 per cent.

Emkay Global, a brokerage, warned in a client note that key parts of the BJP’s reform agenda, including privatisation and the kinds of labour and land market reforms demanded by foreign manufacturers, would be “off the table” if the loss of its majority was confirmed.

Shumita Deveshwar, an economist at GlobalData.TSLombard, warned that coalition politics could force the BJP — which has touted its responsible fiscal policies to foreign investors — into “competitive populism”.

“Any whiff of political volatility makes the markets nervous,” she said. “The markets see that if the BJP doesn’t have a majority then passing reforms through parliament will be harder”.

Both the BJP and the INDIA alliance may now seek to shift the balance of power by inducing rival members of parliament to defect to their sides.

“It will be back to pre-2014 . . . There will be the compulsions of coalition politics,” said Seshadri Chari, a pro-BJP commentator. But he added that the prime minister knew the “art of management”

“Politics is all about management. I don’t see any difficulty as far as Modi is concerned in handling the situation,” Chari said.

Modi went into the election, which ran from April to June 1, enjoying high popularity thanks to his potent blend of Hindu nationalist politics, economic reforms supportive of big business, and development spending.

His government has spoken of building a $10tn economy by the mid-2030s, more than twice its current size, and vowed to lift the country to developed-economy status by 2047.

But analysts said Modi appeared to have miscalculated the depth of anti-incumbency feeling and economic dissatisfaction. The BJP seemed to struggle on the campaign trail as the opposition seized on India’s widening inequality.

Modi, who has been unable to effectively address widespread joblessness despite rapid economic growth, responded by doubling down on polarising religious rhetoric about India’s Muslim minority. But the margin of the prime minister’s victory even in his own constituency of Varanasi was on Tuesday on track to fall from past elections.

The Indian National Congress, the BJP’s main rival, ran on a platform of boosting welfare spending and creating more government jobs.

“I am happy with the verdict,” said Sumit Kumar, a 22-year-old jobseeker in Delhi. “I did not vote for Modi because he could not give jobs to the youth.”

But some foreign investors were optimistic about Modi’s prospects. “I do not expect Modi to change his policies,” said Alessia Berardi, head of emerging macro strategy at the research arm of European asset manager Amundi. “Even continuing with what we had so far, I think that is good for investors, and for business.”