Our planet is changing. So is our journalism. Keep up with the latest news on our Climate and Environment page.

Sign up here to get this newsletter in your inbox every Thursday.

This week:

- A new EV hitting the streets? Electric ice cream trikes

- An iceberg the size of Las Vegas breaks off in Antarctica

- This Ontario winery is testing new tech to fight age-old threat to grapes

A new EV hitting the streets? Electric ice cream trikes

On hot days at the park, children scramble with glee when they hear the carnival jingle of an approaching ice cream truck. I do have a soft spot for a twist cone on a hot day, but I’m put off by the black smoke and diesel fumes that spew from many aging ice cream trucks in Toronto.

Of course, there are greener alternatives.

Many Canadians remember the Dickie Dee ice cream carts full of Fudgesicles and Drumsticks that teenage vendors pedalled through streets and parks across the country in decades past, ringing their bells as they went.

It’s what Perry McGeough did for a summer job as a young teen in Saskatoon in the early 1970s.

“I ate a lot of my profits, to be honest,” said McGeough. “I don’t think I was in it for the money.”

The technology did have some downsides. The carts used dry ice and ice packs to keep the treats cold, and McGeough said some days his hands would be burned raw (dry ice is –78 C).

The single-speed tricycle front-loaded with a huge freezer full of ice cream did fine on flat terrain, but hills were challenging.

WATCH | Young teens peddle ice cream in the 1980s:

Sean O’Shea reports on the young ice cream peddlers of Saskatchewan in the summer of 1985.

Unilever bought Dickie Dee in 1992 and shut down the ice cream trike business in the early 2000s. Some vintage carts still exist. Even recently, they’ve been pedalled around by independent operators or rented out for events. Companies such as The POPcycle in Fredericton have even had new tricycle ice cream carts custom-built.

Meanwhile, McGeough grew up to build, import and sell food trucks and food carts through his company McGeough Consulting, now based in Windsor, Ont. Some years ago, he noticed a new technology: electric ice cream trikes, which were being built in China.

A lithium-ion battery helps the rider pedal up hills, while a lead-acid battery powers the freezer — no need for the pollution-spewing diesel engines and generators used by ice cream trucks. And the cart can plug into a wall socket for recharging if needed.

“I’m like, ‘That’s a pretty cool idea,'” McGeough said. “It eliminates dry ice, it eliminates freezer packs … it just makes it really simple.”

After trying the cart out himself, he started selling it about four years ago. He said he’s sold about 50 across Canada.

Aied Muhareb of Edmonton and his business partner bought three. “It’s just something different — electric, friendly to the environment, it’s easy to use,” he said.

Muhareb dreamed of using them to sell ice cream in Edmonton parks. “It’s a good business … if they give us a permit,” he said. “Makes people happy, you know.”

But it hasn’t been a smooth ride. After four years of trying to get a permit from the City of Edmonton, he’s all but given up and sold two of the three trikes.

The city told CBC News that under its mobile food vendor regulations, carts can’t roam from park to park as Muhareb and his partner envisioned (and as Dickie Dee carts used to). The city also only permits non-motorized carts.

In the meantime, Muhareb is focusing on his dessert shop in the West Edmonton Mall called Choco-Dip.

McGeough said city regulations can be challenging, and other vendors have had better luck taking the trikes to private events, such as festivals or weddings. He took one to his son’s school for an end-of-year celebration last year.

As for me, I hope to see a pedal-powered ice cream cart in local parks someday so my family and I can enjoy ice cream and fresh air at the same time.

— Emily Chung

Old issues of What on Earth? are here. The CBC News climate page is here.

Check out our podcast and radio show. In our newest episode: In our newest episode: Water is scarce — especially in Gaza, because of war and climate change. We speak to the executive director of the Arava Institute of Environmental Studies about how climate solutions can help build peace in a climate hotspot like the Middle East. And, the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea delivered a historic opinion this week about climate impacts on small island states. We hear an update from a Tuvaluan lawyer.

What On Earth16:02How Palestinians and Israelis are connecting over climate

What On Earth drops new podcast episodes every Wednesday and Saturday. You can find them on your favourite podcast app, or on demand at CBC Listen. The radio show airs Sundays at 11 a.m. ET, 11:30 a.m. in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Check the CBC News Climate Dashboard for live updates on wildfire smoke and active fires across the country. Set your location for information on air quality and to find out how today’s temperatures compare to historical trends.

Reader feedback

Bianca Braga de Carvalho:

“I’ve been a reader of the What on Earth? newsletter for years now, and I’m intrigued about the story on fireproofing Whitehorse. I wonder what a biologist’s opinion would be about the conservation matter (and at this point, I’m only talking about nature). Suppressing a whole forest while planting a different species wouldn’t take a toll on the species of animals that have lived there forever? It’s a genuine question!”

Thanks for your question, Bianca. The fire break isn’t the entire forest. It’s a strip ranging from a few hundred metres to two kilometres wide that’s being cleared of fast-burning conifers. It will be largely replanted with aspen, a slower-burning species. Concerns about the impact on wildlife were brought up during the project’s environmental assessment by groups such as Ta’an Kwӓch’ӓn Council and Environment Canada. The final decision from the Yukon Environmental and Socio-Economic Assessment Board requires work on the fire break to stop when caribou are detected until they have passed through, and the project needs to comply with the Migratory Birds Convention Act and Regulations because this is a bird nesting area.

During the public comment period for the Copper Haul Road Fuelbreak, the Ta’an Kwӓch’ӓn Council noted “the potential for impacts to wildlife through habitat reduction, changes in migration, disturbance from heavy machinery and increased traffic, as well as the potential for increased sedimentation within streams flowing through the project area.”

TKC added that it “wishes to ensure that the proposed mitigations as outlined in the Copper Haul Road Fuelbreak [proposal] are implemented. This includes the restriction of clearing to times outside the window for breeding bird activity, the buffering of creeks, the storage of fuel and an adequate spill response plan.”

Have you tried buying a small car in recent years? Has it been difficult? We are working on a feature about the ubiquity of SUVs in Canada, and would love to hear your stories about trying to purchase something other than an SUV or truck (new or used).

Write us at [email protected].

Have a compelling personal story about climate change you want to share with CBC News? Pitch a First Person column here.

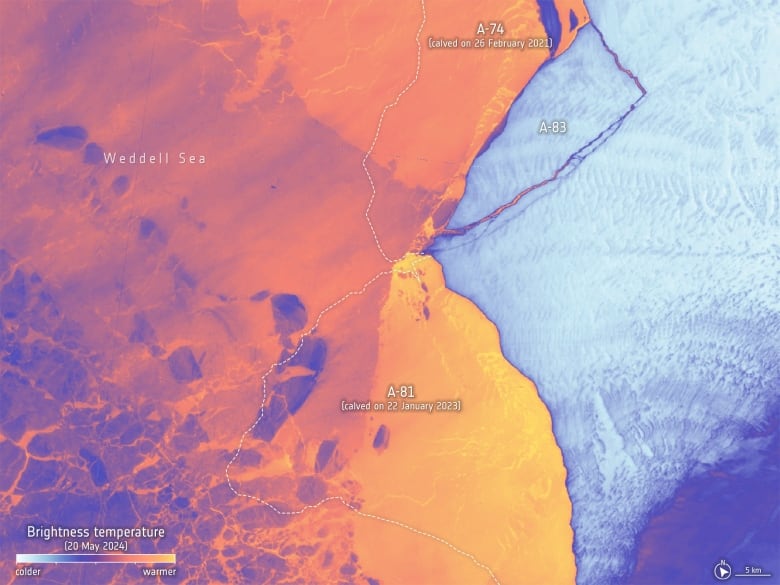

The Big Picture: An iceberg the size of Las Vegas breaks off in Antarctic

Iceberg calving events — when a massive chunk of ice breaks off a once-stable shelf — are some of the most visible and worrying signs of climate change. On May 20, we got another one: an iceberg larger than the city of Las Vegas broke free from the Brunt Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

The spectacular break was captured by satellites in orbit, such as in the above image combining shots taken by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite and NASA’s Landsat 8. The berg, dubbed A-83, is the third major calving event to affect Brunt in the last four years. The culprit is a fracture ominously named the Halloween Crack, since it was first detected on Oct. 31, 2016.

Floating bergs don’t directly contribute to sea-level rise, but deteriorating ice shelves do.

“Owing to climate change, Antarctica’s ice shelves are weakening, leading to greater risks of more land ice ending up in the oceans and thereby adding to sea-level rise, something arguably more frightening than Halloween,” the ESA explained in a 2022 blog on the Halloween Crack.

— Jordan Pearson

Hot and bothered: Provocative ideas from around the web

This Ontario winery is testing new tech to fight age-old threat to grapes

Over the rumbling engine of a harvester, a high-pitched hiss emerges: hydrogen peroxide misting into the air. The mist is lit by the ethereal sky-blue glow of ultraviolet lights, housed in giant panels that form a tunnel.

It all looks like it belongs in a biohazard facility, but it’s a new technological solution being tested at Vineland Estates Winery in Ontario’s Niagara region to deal with one of winemaking’s oldest foes: powdery mildew.

“Powdery mildew can be disastrous. We can lose entire crops if not managed properly,” said veteran winemaker Brian Schmidt. The white mould affects the leaves and berries, eventually coating them and destroying the fruit.

For a province that produced more than 75,000 tonnes of grapes last year, a bad year of mildew could waste more than 5,000 tonnes of grapes. And as the climate warms, experts warn these fungal pathogens could grow and spread.

Mildew has been a problem for winemakers for nearly 200 years. A fungus native to the U.S., it ravaged European grape crops in the 1850s before being controlled with sulphur and other methods.

These days, it’s managed with fungicides sprayed throughout the growing season. The chemicals are expensive for wine growers, require strict safety protocols and need to be managed so fungi don’t develop a resistance.

The new system — developed and patented by St. Catharines, Ont., company Clean Works and being tested at Vineland Estates, which grows 40 hectares of grapes — attacks the fungus on the surface of the vine, unlike fungicides, which generally block the fungus from reproducing. The harvester moves over rows of vines and subjects them to hydrogen peroxide, ozone and UV-C light, which is a known disinfectant.

“That combination allows us to be able to rid ourselves of any pathogens in the vineyard, such as downy mildew, powdery mildew, black rot,” Schmidt said, calling it a new tool in the winery’s arsenal to manage these problems more sustainably.

Experts say while this new approach could be effective, key questions remain about how it will affect the plant and deal with internal fungi.

“I think it has promise just because of the layering of those three strategies,” said Megan Fisher, a lab instructor in the biology department at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax.

UV light, hydrogen peroxide and ozone are useful individually, she said, but together they create a short-lived reaction that could have “an even more marked impact on microorganisms.”

That reaction breaks down into oxygen and water, which means no chemicals are left behind.

But Fisher warns that more research is needed to determine if prolonged exposure to this treatment will affect the genetics of the grape crop, which comes back every year from a woody stalk.

For Wayne Wilcox, professor emeritus at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., who has been studying mildew and fruit diseases since the mid-1990s, the method seems “very effective in basically surface sterilizing.” But he said these methods don’t work as well when fungal pathogens strike deeper down.

“The spore germinates and it goes down into the berry or into the leaf and does its feeding down where it’s protected from surface [treatments].”

So far, Schmidt said, a year of trials with the new system has shown that mildew was kept in check when compared with traditional fungicidal spraying — even with last year’s particularly rainy season making conditions more favourable for fungi to thrive.

The system will continue to be tested on two hectares of vines, monitored and measured by scientists at the University of Guelph in southwestern Ontario.

With Earth’s climate warming, experts say fungi will have more opportunities to grow and expand their range. Although wine regions exist across climates, warmer air holds more moisture, which are two key environmental parameters for the spread of fungal pathogens.

“The more our climate shifts, the more likely we are to experience novel pathogens in our own growing environments,” Fisher said. “Having ways to pivot and respond to that kind of threat is good.”

For Allan Schmidt, Brian’s brother and president of Vineland Estates, the system helps reduce waste. Beyond that, the Schmidts see the new system as providing a legacy in sustainable winemaking. They plan to invite colleagues from other wineries to come and see the modified harvester in action this summer.

“We want to share it with the rest of Canada, and ultimately the rest of the world,” Allan Schmidt said.

— Anand Ram

Stay in touch!

Thanks for reading. Are there issues you’d like us to cover? Questions you want answered? Do you just want to share a kind word? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at [email protected].

Sign up here to get What on Earth? in your inbox every Thursday.

Editors: Emily Chung and Hannah Hoag | Logo design: Sködt McNalty