The details in the Facebook post were shocking.

It said nine women in northwestern Ontario were abducted and taken toward the border between Fort Frances, Ont., and International Falls, Minn., at the border, it added, they cried for help and were rescued by border officers.

The post went viral and was shared widely on the internet over the last few days.

But there was one big problem — Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) investigated and found no such kidnapping.

“We wanted to assure the public that the incident did not occur and that there’s no concern for public safety,” said Autumn Eadie, an OPP communications officer

Eadie said the OPP consulted with the U.S. and Canadian border service agencies, and both confirmed the alleged kidnapping didn’t happen. There also weren’t any kidnappings reported to the Rainy River District OPP detachment.

“We do use other investigative techniques, so that would be conducting interviews, patrolling areas where the offence was claimed to have occurred, reviewing security camera footage,” said Eadie.

CBC News has reviewed a screenshot of the original post. The screenshot has since been deleted. The post was an image of block of text, detailing the alleged events. There was no original publication date and the original poster’s profile picture is blurred out.

“My daughter got abducted last night along with eight other women,” read the screenshot of the post, which included an offensive term to describe people from India.

“When they crossed the border and were at the customs, all the abducted women cried for help. That’s how they managed to get help from the customs officers and were freed,” said the post, which also claimed the abductors were arrested.

OPP put out a public notice Wednesday saying the viral post was a hoax.

Later, Borderland Pride, a 2SLGBTQIA+ organization, posted a statement to social media that said: “It was obviously malicious gossip that was intended to cause moral panic and outrage targeting members of a minority group.

“That this message was allowed to spread in our community without question — and was signal-boosted by others so willingly — speaks to the undercurrent of bigotry, prejudice and hatred that we and others continue to push back against on a daily basis.”

Misinformation and disinformation narratives often centre on health or safety concerns, prompting people to reshare them urgently, said Kara Brisson-Boivin, director of research for MediaSmarts, a non-profit organization based in Ottawa that focuses on digital and media literacy programs.

“When we’re operating from those kinds of emotions — fear, anxiety, anger — our ability to authenticate and verify, and our ability to use those critical rational thinking skills, sort of declines,” Brisson-Boivin said.

She said she has seen other instances of inaccurate or false information entered around fear of perceived outsiders circulate quickly on social media.

“A thread through a lot of these types of posts are that oftentimes perpetrators are framed as racialized,” said Brisson-Boivin.

How to spot misinformation online

Brisson-Boivin recommended fact checking posts that make these kind of allegations, by cross-referencing official sources of information such as police, governments and credible news media.

“When we see content that is shared by neighbours, friends and family, we can implicitly trust them as sources because we have a kind of interpersonal trust with them,” she said. “However, in the context of information, they are not necessarily a trusted source in the sense that a news outlet or, or journalists are in that they have a code of conduct and professional practices that they have to uphold in sharing information online.”

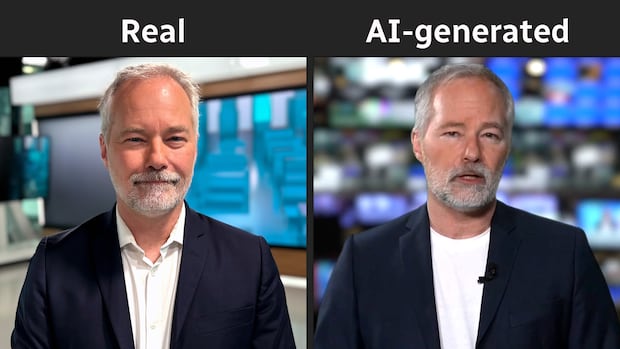

A 24-hour news channel startup based in southern California comes with a twist: all of the reporters and production are AI-generated. CBC’s Jean-François Bélanger explores what Channel 1 is promising and why some are concerned about what it could mean for the news industry.

While the alleged kidnapping in the recent viral Facebook post didn’t happened, people in northern Ontario and beyond have real reasons to be wary of dangers like abduction and human trafficking.

Indigenous women are particularly at risk. According to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls’ final report, Indigenous women and girls are 16 times more likely to be murdered or to disappear than white women.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada maintains a list of nearly 600 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people across the country, spanning 20 years.

Some communities may have a justified distrust of police information, said Brisson-Boivin. In situations where communities aren’t comfortable relying on the police as official news sources, fact checking can still be done on the community level to prevent misinformation.

“It’s about connecting with the people who you do trust, if that is your neighbours in this context, especially in small tight-knit communities and saying, ‘OK, this is circulating. What can we do to verify whether this has actually happened?'”

Sometimes it’s hard to tell what’s real and what’s false online, said Brisson-Boivin. If you do accidentally share something that ends up being false, she said, correcting it is usually better than deleting it.

“We also have a due diligence to say: ‘Hey, I shared something, but it actually didn’t happen.’ I’m not really seeing that.” Brisson-Boivin said. “That kind of intellectual humility would be really important and really helpful.”