This article is an onsite version of our The State of Britain newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good afternoon. The first week of the election campaign is nearly over and it’s already pretty clear there is limited insight to be gained from parsing the Conservative’s increasingly shrill attempts to be “heard”. They are aimed squarely at the base. As for Labour, the party seems determined to say as little as possible. Slim pickings.

My only broader observation thus far is a slightly sad one, which is to say that it’s a depressing indicator of the current “State of Britain” when the governing party is actively running down the reputation and value of its university sector.

The spectacle of a prime minister jubilant at the prospect of cutting access to degrees, rather than improving or expanding them, also sits uneasily with the UK’s long record of failing to provide for those who don’t want a traditional three-year university degree. (See today’s chart)

Which is why this week I wanted to leapfrog the campaign and look forward to how Labour, should it win on July 4, is promising to reboot the operation of government in order to deliver its “five missions”.

To recap, these are: to deliver the highest sustained growth in G7; turn the UK into a green energy superpower; make the NHS fit for the future; create safe streets; and deliver “opportunity for all”.

On one level, this is standard stuff. Pretty much every incoming government says it will boost spending by finding efficiencies while promising to fix Whitehall to improve delivery. It seems only yesterday that Dominic Cummings was writing his “misfits and weirdos” memo, and being taken seriously.

As you’d perhaps expect from the rather stodgier figure of Sir Keir Starmer, Labour’s pitch is less moonshot, more management speak. But ironically one of the oft-cited examples of “mission-led” government was former US president John F Kennedy setting the goal in 1962 of putting a man on the moon before 1970 — as this explainer from the Institute for Government recalls.

So while it’s easy to be sceptical of another new dawn in Whitehall, Peter Mandelson’s remark about the need for “convulsive and disruptive reorganisation” of government that I quoted a couple of weeks ago, has prompted me to consider what mission-led government might look like.

Labour promises it will soon start to flesh out the projects needed to achieve its very broad goals. Comparatively more detail is offered in the pre-flight information about governance and process.

Strip out the connective verbiage from Labour’s missions document, and you are left with something like this:

Cross-cutting mission boards . . . putting citizens centre stage . . . review the institutional landscape . . . hand powers to local leaders . . . publish the data . . . have long-term funding settlements.

According to Jill Rutter and Joe Owen at the IfG, a new government will have to eschew the traditional Cabinet committee approach, which tends to prioritise inward-looking compromises rather than external delivery.

As Rutter puts it:

Conventional cab committees lead to lowest common denominator policymaking. You have a lead department, others weigh in, in so far as they’re interested, knock a few bits off here and there, and you end up with a messy compromise.

The challenge, therefore, is to move from “lowest common denominator” policymaking, to what Rutter calls “seeking the highest common factor”, with ministers focused on what it takes to deliver something, rather than defending their own turf.

To do that, Owen says you could use mission boards in the centre to set high-level direction, but couple them with a separate committee to plan and monitor delivery and “crowd in” expertise from the private sector and local government. The Labour document promises to do this.

Or as one Labour insider puts it. “You need Cabinet committees to sit above the missions and a cross-Whitehall director-general or a minister in charge of each, but both have to be driven from No10 or the Cabinet Office, or nothing will happen.”

That is clearly a break from the recent past, where the past five years has seen government by press release and without strategy, driven often by internal factional disputes and ideological considerations, and frequently flying in the face of the private sector demands.

Among the lowlights were the plans to rip up all legacy EU law in a year; the essentially performative Rwanda legislation; the flip-flops on university expansion and immigration; the five-times delayed Brexit border; HS2 cancellation; and the utterly haphazard delivery of “levelling up”.

Even when it clearly stated an ambition, the government frequently failed to join the dots to deliver it. So it listed lab-grown proteins and novel foods as a key benefit of Brexit . . . but then failed to resource the regulator to make it happen.

It shouldn’t be hard to improve on that performance, but with an important caveat: tinkering with governance structures is really a second-order issue when it comes to delivering change.

The first-order issue is for the governing party to make decisions — and big decisions — early and then go very hard at delivering them. The delivery mechanism is obviously important, but it is ultimately secondary.

To take an example from the last government. It failed in one of its primary missions, levelling up, not because of Whitehall’s poor delivery structures (though those did fail and didn’t help) but first and foremost because Boris Johnson’s government ducked the council tax and local government funding formula reforms that were needed to make a transformational difference.

Applying that argument to Labour, the real transformation will come not from rejigging cabinet committee structures but taking big, brave decisions (on fiscal rules, public investment, planning reform, Europe and trade). Decisions which — as Tony Blair once observed — have to be made very early in the journey, when the political stock of a new government is at its highest.

A crucial corollary of that is establishing whether the Treasury is a team player in the government’s missions, or an obstructive gatekeeper whose job is to say “you can’t do that”.

Because in the end, once core spending is accounted for, if there isn’t money for the additional missions they won’t happen. The way Whitehall currently functions, when things get tight, a 25-year-old from the Treasury will pop up and put a red line through it.

Put another way, it is about seeing the wood for the trees. Whitehall is indeed battered and bruised from the past eight years. The bureaucracy has grown flabby; talent has haemorrhaged to the private sector.

But if Starmer’s Labour, innately cautious and incrementalist as it appears to be, thinks that fixing Whitehall is a proxy for fixing Britain, it will have engaged in a kind of distraction therapy, rather than confronted the root causes.

Britain by numbers

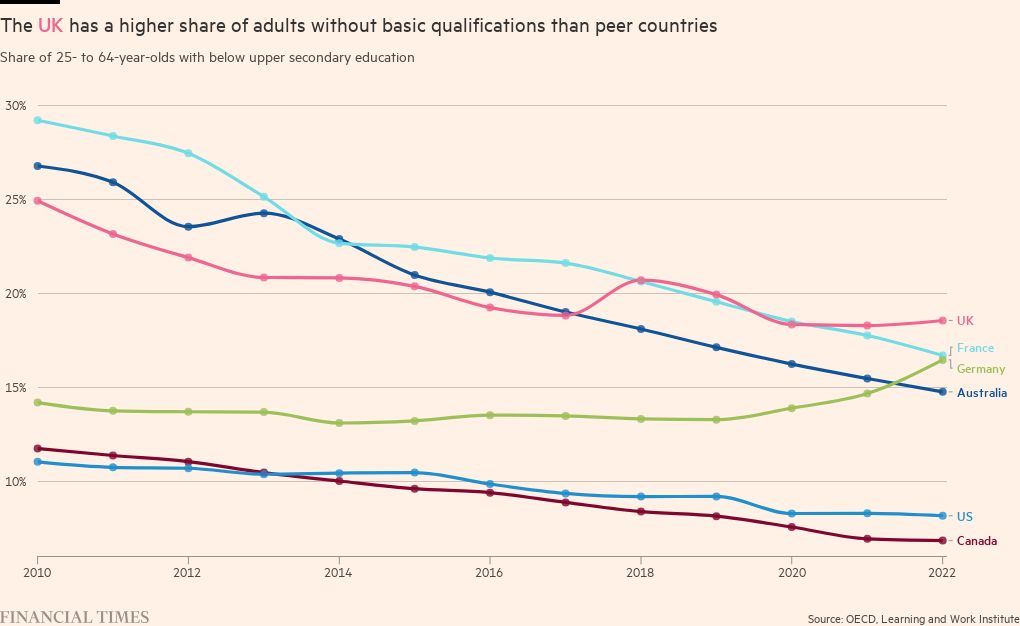

This week’s chart comes from a new report from the Learning and Work Institute, a think-tank, which reveals the UK’s poor record on skills training, Amy Borrett writes.

Almost a fifth of working-age adults in the UK do not have basic qualifications, more than twice the share in the US and Canada.

While there has been some improvement over the past decade, the UK has not kept pace with peer countries, falling behind the likes of France and Australia in recent years.

The UK’s slow progress is the result of punitive cuts to the adult education budget, with government funding per person down more than a quarter and employer funding falling by a fifth in real terms since 2010.

Meanwhile, other countries have shown that — with investment — rapid progress is possible. France has almost halved the share of the population leaving school without basic qualifications since 2010 using targeted policies such as individual training budgets and cost-of-living support for adults in training.

In the UK, apprenticeships form the cornerstone of adult skills training but the system has underperformed since it was introduced in 2017.

Currently funded by a levy on large employers, apprenticeships have been criticised by education leaders for distorting incentives and channelling money away from younger workers.

An FT opinion article earlier this year by former government education adviser Alison Wolf argues that fixing the apprenticeship system would be a vote winner, but the current system “completely fails to tackle the yawning skills gaps” and Labour’s plans “risk making things worse”.

Rishi Sunak announced plans this week to create 100,000 more high-skill apprenticeships a year by shutting down “rip-off” degree courses, but fell short of promising to reform the levy.

Addressing the skills divide will be critical to unlocking economic growth in the next parliament. Skills shortages are expected to cost the UK £120bn by 2030 as the number of professional jobs grows and technological change drives up the qualifications needed in existing jobs.

Ramping up employer investment in skills is also key. For an incoming government, this is as much about improving economic growth and providing political stability as it is as about apprenticeship reforms.

On the current trajectory, one in eight UK workers will have no basic qualifications in 2035, according to the Learning and Work Institute. An improvement, but still a far cry from the one in 20 workers projected in France and Canada.

The State of Britain is edited today by Georgina Quach. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Inside Politics — Follow what you need to know in UK politics. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here