roars and whispers from the finest living painter of animals

In October 1933, a few months after the establishment of an early Nazi concentration camp at Dachau, a black panther broke out of the Zurich zoo. The tropical creature sneaked through wintry Alps and Swiss suburbs, unsure what to do with her freedom. For 10 weeks, she rambled, leaving not a single pawprint in the snow. Her adventure ended unheroically: a hungry farmer found the weakened creature hiding under a barn — and ate her.

Scenes from that great escape irradiate the Morgan Library in New York’s mini retrospective of Walton Ford, our finest living painter of animals. He presented the Morgan with a portfolio of 63 studies that come together, supplemented by a few of his huge, hyper-realistic watercolours, in a crackling composite portrait of the artist’s mind, Walton Ford: Birds and Beasts of the Studio. Though the show is compressed into a small suite of galleries, it ranges over a vast terrain of mythology, melancholy and virtuosity.

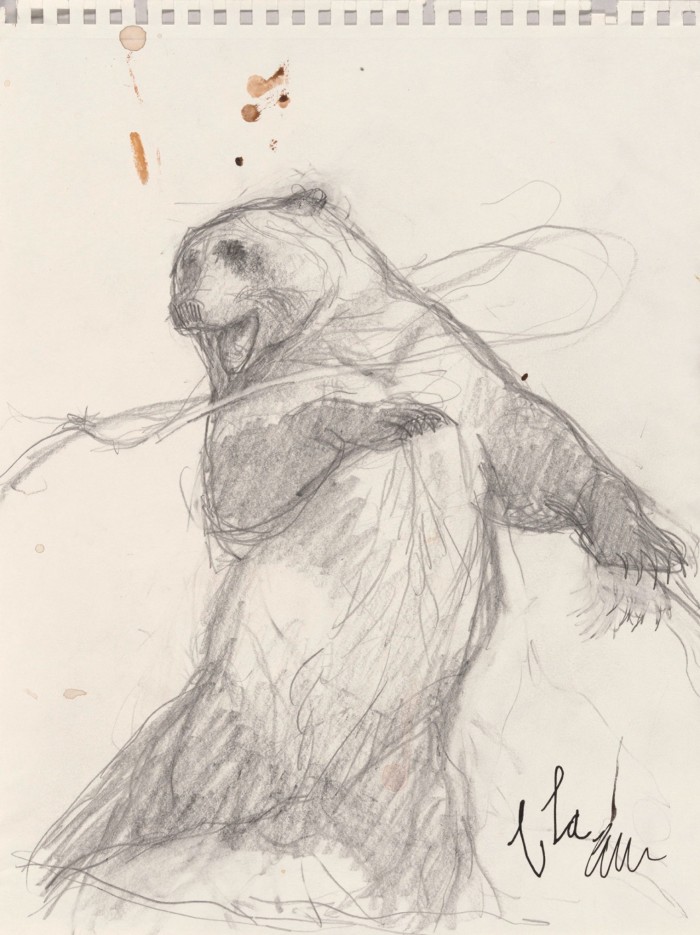

The story of the panther’s life on the lam came to him from the dry second-hand account of Heini Hediger, Zurich’s postwar zookeeper, which Ford fleshed out with his own fantasies. He saw the panther as “an inky spectre, floating above the powder, leaving no spoor; striding through the air”. That vision yielded drawings of a spirit animal perched aloft on a column of smoke. Other sketches form a sequence like a movie storyboard, sometimes from the perspective of frightened villagers, often, from her point of view.

The studies build to the series’ most perfect picture, a large-scale watercolour glistening with expressive detail. Just after her escape, the panther lopes towards the viewer across a frozen lake with the Zurich skyline looming on the low horizon. Her eyes glow gold, her lips part to reveal a pink maw and a glimpse of deadly incisors, but she’s a figure of vulnerability and temporary liberty, rather than menace, a lone escapee driven by terror and exhilaration. The painting isn’t an allegory, but it does evoke the flight of a plantation slave heading north, or a Jewish person on the run from the Gestapo.

Ford doesn’t visit zoos or go on safari; rather, he encounters his bestiary in books, finding inspiration in naturalists’ accounts, legends and fairy tales. “I search for stories of how animals live,” he says, “not only how animals live in nature, but also how they live in the human imagination. I try to distil what I’ve learned into images — to paint very large paintings of beasts, beasts carrying these literary burdens.”

Art informs his perception of nature too. His list of formative experiences includes a visit to Giotto’s frescoes at the Church of St Francis in Assisi, with their graphic-novel-like illustration of the friar’s life. Ford was reared on comic books, which impressed him with their narrative concision and dramatic use of detail.

To prepare for the current show, the Morgan sent him rummaging through its collection in search of his favourite animal art. He emerged with enough prints and drawings to stock a superlative final gallery, alive with Delacroix cats, lions by Rosa Bonheur and a Rembrandt etching of a slumbering boar. (He is less interested in nature photography, which he feels rarely does justice to the texture of a hide or the twitch and shine of a snout. “Photos never really show fur properly,” he has said. “They blur it out for whatever reason.”)

His most important imaginarium is the American Museum of Natural History, which he visited regularly as a child and where he gathered a cortege of taxidermied companions. He still returns to plumb archives and study embalmed specimens, which can be more satisfying than living creatures. “They don’t move, they don’t go to sleep, they don’t hide like they would at the zoo,” he explains.

A coyote with its head thrown back, jaw cracking into a howl, looks not only animate but realer than the preserved original in the American Museum of Natural History, which sits before a painted tableau of Yosemite national park. Ford is a fan of those meticulously realistic dioramas, which he apparently believes outdo anything at the Met: “You will not find any landscape painting in New York better than these backgrounds,” he has said.

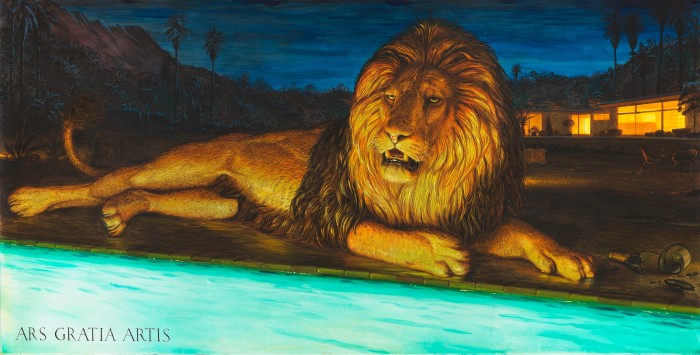

He has adapted the dioramas’ theatrical aesthetic with a satirical eye towards humans and immense sympathy for the animals that cross our paths, especially those we imbue with symbolic significance. In “Ars Gratia Artis”, its title borrowed from the MGM motto, he dreams about how the lion in the studio’s logo might live after his roaring days are done. The retired feline sprawls indolently by a pool next to a glass-walled Modernist mansion. The Hollywood Hills rise at his tawny shoulders as the sun sets behind the palms.

This magnificent creature, spotlit and ready for his close-up, is a leonine Norma Desmond: pampered, washed up and undoubtedly drunk. (A champagne bottle lies smashed in the foreground.) Once the embodiment of showbiz pride, he’s now an emblem of luxurious endurance, eyes gleaming yellow like the inside of his vast house.

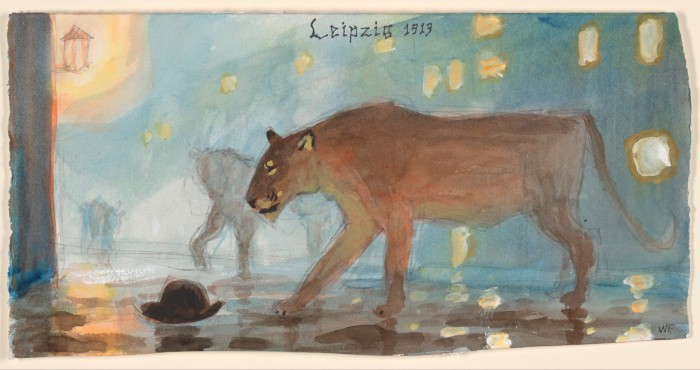

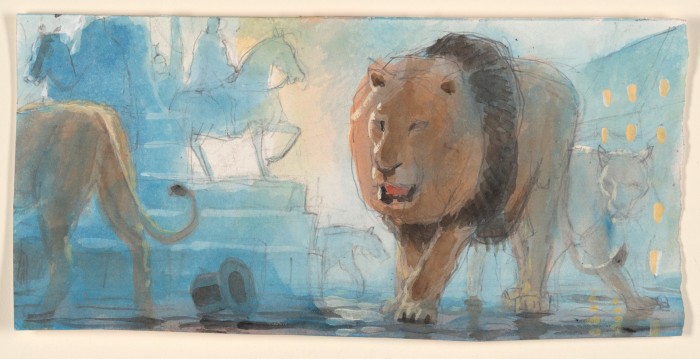

Lions are plentiful at the Morgan, perhaps because they are so regal in their own habitat and so pathetic beyond it. Ford used his sketchpad to revisit the story of a foggy night in 1913, when a city tram collided with a circus caravan, allowing eight lions to amble out on to the streets of Leipzig in Germany.

Researching the case, the artist found newspaper accounts illustrated with scenes of instant mayhem. Animals erupt from cages. Men scurry and women scream. Chaos prevails. Ford took a more nuanced approach, visualising events from the animals’ standpoint and letting them unfold over time. Lions wander through the early-20th-century city, which is hazed and brightened by the contrapuntal illumination of gas lamps. They try to get their bearings, unaware that they might be sowing fear.

His subject is not rage but confusion, the animals’ sheer mystification in the face of urban life: “I imagined one of the hats that had been left behind: the lions approach it like a strange object, like a turtle or something.” Those scattered items — a bowler here, an umbrella there — look weird to us, too. They are totems of Europe on the precipice of the first world war, a civilisation that failed to reckon with its own savagery.

The real story ended in predictable carnage: six of the lions were killed in a barrage of bullets. The remaining two were recaptured and sent back to lives of labour in the circus. It’s part of Ford’s mastery that he was able to elevate a sensational and sordid tale into grand and beautiful tragedy.

To October 20, themorgan.org

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen