Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Activity on China’s equity capital markets on the mainland and beyond has slumped to multi-decade lows, highlighting how the loss of momentum in the world’s second-largest economy has weighed on investor confidence.

Chinese companies have raised just $6.4bn in mainland IPOs, follow-on and convertible share offerings so far this year — the lowest level on record, according to Dealogic data.

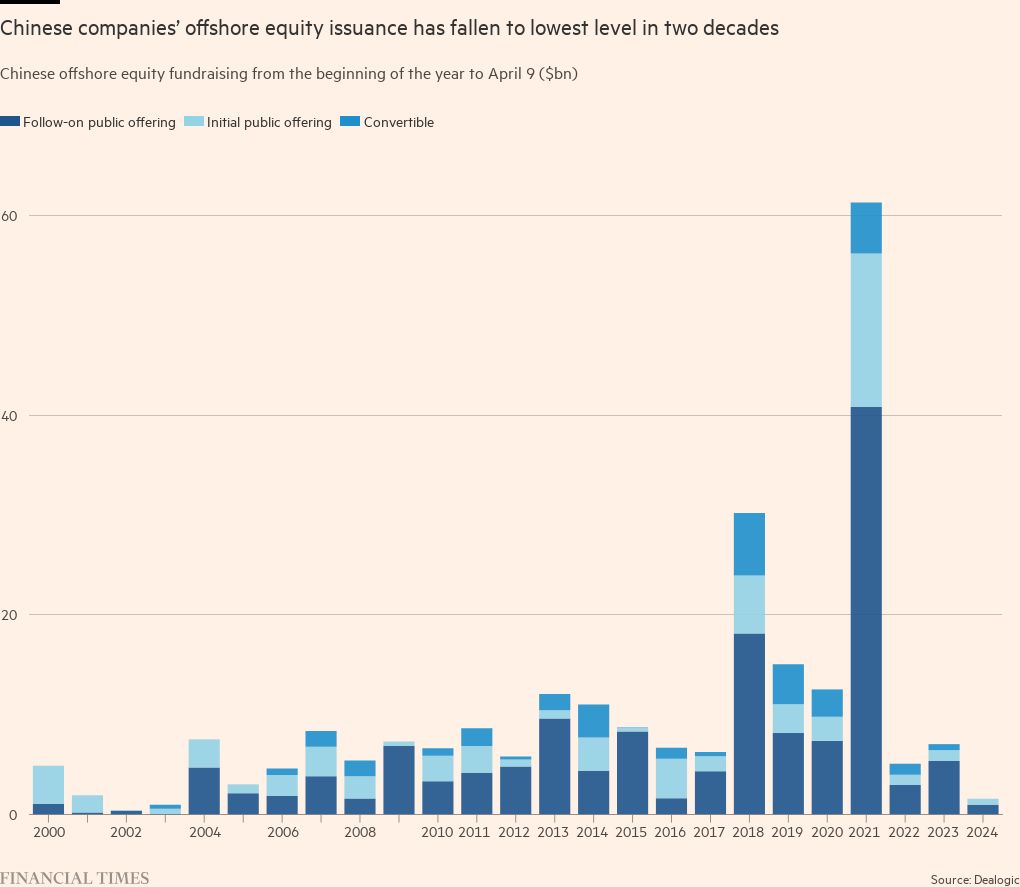

Their fundraising in offshore markets including Hong Kong is $1.6bn, the lowest year-to-date since 2003. China’s outbound M&A of $2.5bn is the lowest recorded amount over the same period since 2005.

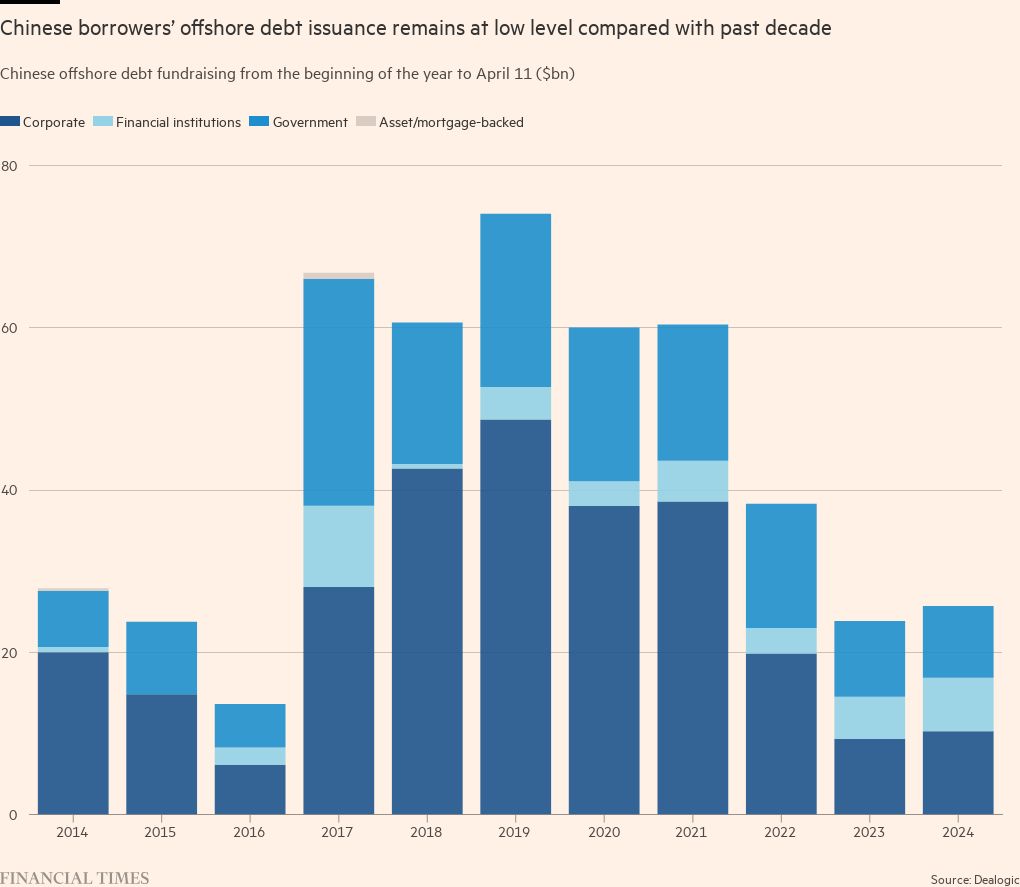

On international bond markets, Chinese companies, banks and government borrowers have issued $26bn so far this year, slightly above last year’s $24bn but otherwise the lowest level since 2016. On the mainland, borrowing of $246bn is up 17 per cent on last year.

“In terms of global investor interest in China, it’s definitely the worst I’ve seen in my career,” said Wang Qi, chief investment officer at UOB KayHian in Hong Kong, who began working in finance in the 1990s.

“It doesn’t matter what type of investor you are, it still looks murky,” said one person involved in China’s financial markets who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The economic uncertainties haven’t yet dissipated.”

China’s economy grew by 5.2 per cent last year, but an anticipated strong rebound failed to materialise after the lifting of strict three-year Covid-19 pandemic measures at the start of 2023. Consumer prices last month rose 0.1 per cent, but have been mired in deflationary territory for much of the past year.

The capital markets data reflect a climate where China’s financial system has become increasingly isolated, despite the ending of the pandemic. At this stage in 2021, Chinese companies had issued $61bn of equity outside the country, 39 times more than the volumes so far in 2024. Corporates had issued $39bn of bonds, almost four times the current rate.

International banks, which for years sought to make inroads into China’s vast financial system, have had to grapple with shrinking levels of activity. Swiss agrichemicals group Syngenta last month withdrew its long-standing plans to list in Shanghai, while increased scrutiny of listings from the country’s securities regulator has seen other plans cancelled. New equity issuance onshore is down 83 per cent year-to-date.

International firms have also had to navigate mounting geopolitical tensions between Beijing and Washington, where a select committee has scrutinised American business on the mainland.

Tensions weighed on outbound M&A activity last year, but by this stage of 2023, volumes were more than three times higher than the current rate.

On international bond markets, a rise in borrowing costs has made it relatively more expensive for Chinese issuers to borrow outside the country, bankers say. In contrast to central banks in North America and Europe, China has cut key borrowing rates over recent years.

“For China or China-related companies, they are more focused on core business and more disciplined capex,” said Mandy Zhu, China head of global banking at UBS.

Property developers, formerly the mainstay of Asia’s high-yield bond market, have in effect stopped borrowing internationally for the past two years after a government crackdown on leverage derailed their business models.

China’s CSI 300 index of Shanghai- and Shenzhen-listed stocks is up 3 per cent this year, but is down around 40 per cent since a peak in 2021.