In the dozen years she’s worked with the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, executive director Brittany Graham has lost count of the people she’s seen succumb to British Columbia’s toxic drug crisis.

Sunday marked eight years to the day since the province declared a public health emergency related to the deadly toxic drug crisis, and Graham said it’s a sombre anniversary as she and others in public health reflect on the thousands of deaths.

“Last time I did a count it was somewhere in the 65 to 75 person range of people, and to give that perspective to people, that’s more than a yellow school bus full,” Graham said in an interview Sunday, referring to deaths of people she’s known in her dozen years working with the support network.

“That’s a lot of people that no longer exist, who were kind and thoughtful and just really lovely people.”

The B.C. government and public health officer declared the emergency on April 14, 2016, and since then more than 14,000 people have died, most of them from the highly potent opioid fentanyl.

Toxic drugs are now the leading cause of death for people aged 10 to 59 in B.C., according to the B.C. Coroners’ Service, accounting for more deaths than homicides, suicides, accidents, and natural disease combined.

Two First Nations have also declared local states of emergency over drug poisoning deaths in the last several weeks, with the First Nations Health Authority warning that First Nations people are dying at nearly six times the rate of other B.C. residents.

In a statement released Sunday, Premier David Eby said the toxic drug crisis has had a “catastrophic impact” on families and communities.

“There is much more to do,” Eby said. “And together, we can end a crisis that has taken far too many of our neighbours, friends and family members.”

Advocates ask for regulations similar to alcohol

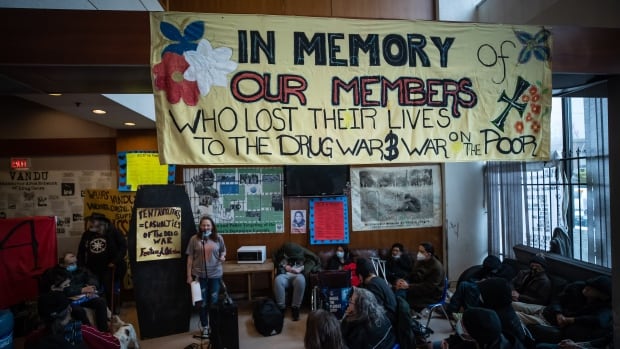

Graham said a community town hall on the anniversary of the declaration will allow members of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside community to “grieve collectively” and discuss how to “build their way forward.”

But with both provincial and federal elections looming, Graham fears “the toxic politics is what’s going to be killing people next,” as politicians vie to win votes touting what she says are ineffective solutions to the deadly crisis.

She said what’s needed are regulations for drugs that are similar to those for alcohol.

“In many ways, alcohol is one of the most toxic substances you can consume,” she said.

“But because we give people education, we have minimum pricing standards because we have regulations on where you can access it and where you can drink it, those are all ways in which harm reduction and public health are being utilized towards that specific substance,” she added.

“We don’t have any of that happening towards illicit substances at the moment. This is a toxic drug crisis, so unless we have regulation, we’re always going to have a higher and higher amount of drug deaths.”

Eby noted that toxic drug deaths have taken a toll on friends and loved ones of those who’ve been lost, and also on front-line workers who deal with the ongoing damage done by addiction and drug deaths.

He said the situation needs to be recognized as a “health crisis,” adding his government is trying to build and improve the province’s mental health and addictions care systems.

Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said in the province’s statement that drug users come from “all walks of life,” often dealing with trauma, and those who try to free themselves from addiction have to go through a recovery process that isn’t “linear” or hinged upon total abstinence, she said.

“We must continue to have courage and to be innovative in our approach to this public health crisis that continues taking the lives of our friends and families in B.C. daily,” Henry said.

Graham said all governments need to rethink their approach to drug users by recognizing the ways support systems fall short and leave those seeking help unable to get treatment when they decide to seek it.

At the same time, she said many city governments have pushed for laws to ban public drug use, pushing users further to the margins with nowhere to go.

“In the middle of this overdose crisis, we’ve decided to have public use legislation to say, ‘now you can’t be outside,”’ she said.

“These municipalities do not want to fix anything. They just want people to go away — and these are real people with real families, with real lives, with real jobs,” she added. “The further you push people away, the bigger this crisis will get.”