Brian Mulroney — who, as Canada’s 18th prime minister, steered the country through a tumultuous period in national and world affairs but left office deeply unpopular — has died. He was 84.

His daughter Caroline Mulroney shared the news Thursday afternoon on social media.

“On behalf of my mother and our family, it is with great sadness we announce the passing of my father, The Right Honourable Brian Mulroney, Canada’s 18th Prime Minister. He died peacefully, surrounded by family,” she said on X, formerly Twitter.

Mulroney was one of Canada’s most controversial prime ministers. Unafraid to tackle the most challenging issues of his era, Mulroney pursued politics in a way that earned him devoted supporters — and equally passionate critics.

1/3<br>On behalf of my mother and our family, it is with great sadness we announce the passing of my father, The Right Honourable Brian Mulroney, Canada’s 18th Prime Minister. He died peacefully, surrounded by family.

—@C_Mulroney

Mulroney was a gifted public speaker and a skilled politician. As prime minister, he brokered a free trade deal with the U.S. and pushed for constitutional reforms to secure Quebec’s signature on Canada’s supreme law — an effort that ultimately failed.

He introduced a national sales tax to raise funds against ballooning budget deficits, privatized some Crown corporations and stood strongly against racial apartheid in South Africa during one of the most eventful tenures of any Canadian prime minister.

“Whether one agrees with our solutions or not, none will accuse us of having chosen to evade our responsibilities by side-stepping the most controversial issues of our time,” Mulroney said in his February 1993 resignation address.

“I’ve done the very best for my country and my party.”

A fateful friendship

Mulroney was born to working class Irish-Canadian parents in the forestry town of Baie-Comeau in 1939. His father was a paper mill electrician in this hardscrabble outpost in Quebec’s northeast.

Mulroney grew up with a bicultural world view in an isolated community split between French and English speakers — an upbringing that would prove to be politically useful later.

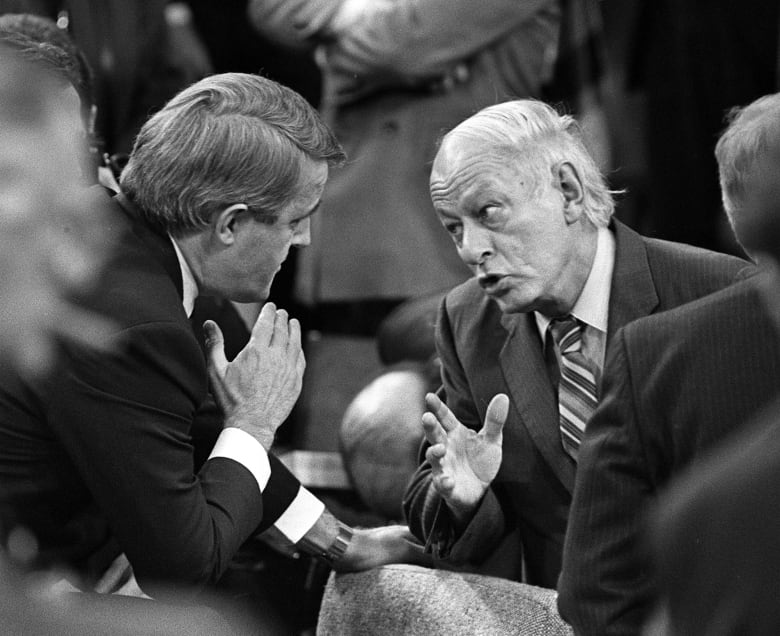

Mulroney became interested in Conservative politics through a fateful friendship with Lowell Murray, a future senator and cabinet minister in his government. Murray convinced his charismatic classmate to join the Progressive Conservative campus club at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, N.S.

A lawyer by training, Mulroney made a name for himself in his home province as an anti-corruption crusader. After violence erupted at the James Bay hydroelectric dam construction site, Mulroney was brought in to investigate Mafia ties as the lead member of the Cliche commission reviewing the bungled project.

Following a failed Progressive Conservative leadership bid in 1976, Mulroney took the reins of the party after organizing opposition to then-leader Joe Clark at the 1983 leadership convention. Mulroney — who had never previously held elected office — unseated the former prime minister from the leadership on the strength of his support among delegates from Quebec.

With the Liberals faltering in the polls, Mulroney led the PCs to a majority victory in the 1984 campaign — one of the largest election landslides in Canadian history. While Pierre Elliott Trudeau had been replaced by John Turner as Liberal leader by the time the 1984 campaign began, the election was widely seen as a referendum on Trudeau’s sometimes turbulent time in office.

Mulroney would win again in 1988 after voters backed his plan to sign a free trade agreement with the U.S. — easily the most consequential policy of the Mulroney era.

‘Irish Eyes are Smiling’

Mulroney was elected to office in 1984 promising to “refurbish” the Canada-U.S. relationship after years of tension. He fended off claims from the Turner-led Liberal Party that a free trade deal with the U.S. would diminish Canada’s sovereignty and turn the country into a ”51st state.”

During a widely watched televised leaders’ debate in 1988, Turner accused Mulroney of selling out Canada. “You don’t have a monopoly on patriotism — and I resent the fact, your implication that only you are a Canadian,” Mulroney fired back.

Mulroney would be re-elected with another majority government — the first time a conservative prime minister had won two consecutive majorities since Sir John A. Macdonald.

Trade between the two countries grew dramatically after the free trade deal was ratified and the economies became even more intertwined after nearly 100 years of protectionism came to an end.

“Our message is clear here and around the world — Canada is open for business again,” Mulroney said at the 1985 “Shamrock Summit” alongside U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

The two men, both of Irish extraction, famously sang lines from the folk song When Irish Eyes are Smiling at that Quebec City meeting. The musical interlude was celebrated by some as a sign of thawing relations between the two countries — and derided by others as a sign of Canada kowtowing to its powerful neighbour.

Mulroney improved Canada’s relationship with the U.S and pushed Reagan to sign the acid rain treaty to curb sulfur dioxide emissions that were destroying waterways. He also signed a North American air defence modernization agreement to better protect the continent from a ballistic missile attack.

Former U.S. president George H.W. Bush considered Mulroney a close personal friend — Mulroney was Bush’s last guest at Camp David, the presidential retreat — and often sought his counsel on Cold War-related matters as an alliance of western nations negotiated an end to the Soviet Union with Mikhail Gorbachev.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would tap Mulroney’s deep U.S. connections in 2017-18 as the NAFTA renegotiation efforts started to go sideways. Mulroney, who owned a home in Palm Beach, Fla. — not far from then-president Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago — was a useful intermediary between Trudeau’s Liberal government and the Republican administration.

A delicate dance with Quebec and a failed accord

During his time in federal politics, Mulroney assembled an electoral coalition of western populists, Quebec nationalists and traditional Tories — an alliance that succeeded in keeping the Liberals out of power for nearly 10 years.

Mulroney’s first landslide majority win — the PCs captured 211 of 282 seats in the Commons in the 1984 vote — gave him the leeway to make fundamental reforms to the Canadian state. Under Mulroney’s leadership, dozens of Crown corporations were sold to private interests, including Air Canada. He also scrapped Trudeau’s much-maligned National Energy Program, a decision welcomed by many westerners.

That electoral coalition eventually would collapse after the emergence of the Bloc Québécois and the Reform Party — groups that capitalized on regional grievances that grew even more stark during Mulroney’s time in office.

Mulroney — who stressed the importance of Quebec to a successful conservative movement during his party leadership bid — trounced his Liberal opponents in the province with a promise to bring Quebec onside with the Constitution.

In 1981-82, the separatist Quebec government led by René Lévesque and the Parti Québécois refused to sign Trudeau’s repatriated Constitution Act, fearing the Charter of Rights and Freedoms would centralize power in Ottawa and dilute provincial influence.

In an attempt to heal those wounds, Mulroney brokered the 1987 Meech Lake constitutional accord with Quebec — then led by federalist Liberal Premier Robert Bourassa — and the other provinces. The accord would have recognized Quebec as a “distinct society” within Canada and would have extended greater powers to the provinces to nominate people for federal institutions like the Senate and the Supreme Court of Canada.

The accord also would have bolstered the provinces’ role in the immigration system and made changes to how social programs were to be funded — allowing provinces to opt out of some programs and accept federal funding to create their own.

While initially popular with voters — many English Canadians believed this overture to Quebec would silence separatism and prevent a repeat of the 1980 sovereignty referendum — the deal crumbled after Trudeau emerged from retirement to oppose it. The former PM accused Mulroney of conceding too much to the provinces and argued the accord would “render the Canadian state totally impotent.”

Many in English Canada also grew leery of recognizing Quebec as a “distinct society.” Ultimately, the provinces failed to ratify the deal by its deadline, with Newfoundland and Labrador and Manitoba as notable holdouts.

“It’s a sad day for Canada. This was all about Canada, about the unity of our country,” Mulroney said of the accord’s defeat.

Lucien Bouchard, Mulroney’s Quebec lieutenant and a former colleague at the Cliche anti-corruption commission, angrily left the PC government after the accord failed and formed the Bloc, a party devoted to Quebec’s interests. Bouchard, widely respected in Quebec, torpedoed Mulroney’s support in that province.

Another Mulroney-led attempt at constitutional reform, the Charlottetown Accord of 1992, was later defeated in a national referendum.

A deeply unpopular tax

Amid the constitutional fracas and after the introduction of the deeply unpopular Goods and Services Tax (GST), Mulroney’s popularity declined dramatically. He posted record-low approval ratings at the end of his second term.

After negotiating the free trade deal with the U.S., Mulroney sought to reform the existing manufacturers’ sales tax (MST) system that, he said, put Canada’s exporters at a disadvantage.

That 13.5 per cent tax was largely invisible to the consumer, while the consumption-based GST that would replace it — a 7 per cent levy on all goods and services purchased in Canada — was to be paid directly at the cash register.

With the Queen’s approval, Mulroney stacked the Senate with supporters to get the deeply unpopular bill through the Liberal-dominated upper house.

“It is clearly not popular, but we’re doing it because it’s right for Canada. It must be done,” Mulroney said of the tax in 1990.

In the 1993 election campaign following Mulroney’s departure from the federal scene, then Liberal leader Jean Chretien — hoping to capitalize on voter frustration — made “Axe the Tax” his campaign mantra.

Chretien easily beat Mulroney’s successor, Kim Campbell, but never followed through on his promise to scrap the tax as it raked in billions of dollars in government revenue — money used to pay down Canada’s substantial national debt.

“Quite frankly, it’s interesting to me to sit back many years later, having had to endure the abuse and recriminations and the pounding, and to see that it’s turned out well for Canada. That’s all I wanted,” Mulroney said in 2010.

A break with allies on apartheid

While often associated with two other leading conservative figures of the era — Reagan and former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher — Mulroney broke ranks with some of his closest allies on one issue: apartheid and sanctions against the South African white minority regime.

Reagan and Thatcher were both vehemently anti-communist. They feared that South African black leaders like Nelson Mandela were Marxists intent on turning the country away from liberal democracy. Mulroney, who had long admired John Diefenbaker’s anti-apartheid stance decades ago, saw the state’s system of racist repression as fundamentally unjust.

After his election, Mulroney launched an aggressive Canadian push within the Commonwealth for sanctions to pressure the South African government to dismantle its racist caste system and release Mandela from prison, where he had been locked up for a quarter century.

Upon his release, Mandela spoke with Mulroney by phone to thank him for his advocacy.

“We regard you as one of our great friends because of the solid support we have received from you and Canada over the years,” Mandela told Mulroney, according to the prime minister’s book, Memoirs. “When I was in jail, having friends like you in Canada gave me more joy and support than I can say.”