Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Thursday

Last week I asked if US politics was still about “the economy, stupid”, highlighting the mismatch between solid real wage growth among the lower paid and the weak economic sentiment/support for President Joe Biden. Since then, James Mackintosh (formerly of this parish) wrote to me to point out that poorer groups spend more of their money on food and rent, and their costs rose more than overall consumer prices. Using inflation rates specific to income groups may show a lower real wage rise than the numbers I highlighted last week.

In the same vein, a new research paper co-authored by Lawrence Summers returns to an old debate by pointing out that higher interest rates are themselves a part of the cost of living. The authors show that if we use alternative inflation measures that incorporate borrowing costs better, the dissatisfaction of consumers is more understandable. The exposure to rising rates, too, may vary by income level.

The question these observations raise is a difficult one: which inflation rates should monetary policy try to keep low and stable? The answer must depend on why we care about inflation in the first place. That’s a question for another column, for today I look at another issue where decomposing the aggregate data matters a lot for how to think about conclusions: the productivity divergence between the two sides of the Atlantic.

Both the US and EU economies have performed much better than expected in the recovery from the pandemic, despite the energy crisis, geopolitical risk and monetary tightening. But their achievements are very different. In the US, overall growth has powered ahead, but labour force participation has not recovered to the pre-pandemic rate (the rise in raw jobs numbers comes down to population growth). In the EU, the employment rate is at record highs, including in countries often seen as chronic failures in getting people into work — but growth has stagnated.

Together, these describe a productivity divergence. Labour productivity in the US has grown much faster than in the EU. Why has this happened? The answer matters for how you judge the policy choices on both sides of the Atlantic — in particular, Washington’s much bigger fiscal stimulus and ongoing deficit spending, as well as its tolerance of high unemployment in the pandemic (coupled with historically high unemployment benefits) as against the European preference to subsidise temporary leave schemes that maintained employment relationships.

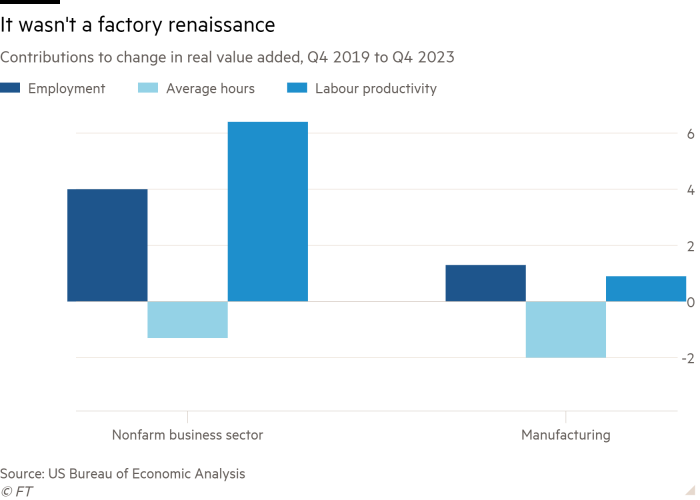

But to be in a position to ask why, we better look first under the bonnet of the US productivity mini-miracle. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis produces quarterly labour productivity data — real output per hour worked — for the major economic sectors. These figures show that in the four years from the end of 2019, real output per hour worked in the US non-farm business sector rose 6.4 per cent. Employment increased 4 per cent, while average hours fell 1.3 per cent — for a total expansion in output of 9.2 per cent and output per worker rising by about 5 per cent.

How much of this was due to manufacturing, the sector that gets so much attention? Factories only employ one-tenth of the whole non-farm business sector, so they need outsized productivity growth to move the aggregate needle. But as it happens, manufacturing has been no success story in the post-pandemic recovery. Labour productivity only grew 0.9 per cent in four years, and even that meagre gain was offset by a fall in total hours worked. (Durable manufacturing performed worse — with an outright fall in productivity, albeit from a higher level — than non-durables.)

The magic, then, must largely have happened in services. It’s harder to find fine-grained and up-to-date data on output per hour worked for narrower sectors. But we can combine the BEA’s more detailed sector-level real value added data (which goes up to the third quarter of 2023) and sector-level employment numbers to measure output per worker (not per hour) in the four years to September 2023. The numbers below refer to productivity in that sense.

How much of the productivity boom is down to reallocation from less productive to more productive sectors, as many of us hoped that the “Great Resignation” would spur? Not much, it turns out — at least in terms of shifts between large sectors. The chart below shows the shift in employment shares (in percentage points of total employment) of each large sector arranged from most to least productive. While there was a small movement into the highly productive financial activities sector, there were also shifts into less-than-average output per worker sectors such as educational and health services. Overall output per worker was, however, boosted by shifts out of low-productivity sectors, such as retail trade and leisure and hospitality. But it didn’t help that employment shares also fell in above-average productive sectors such as manufacturing and rose in below-average ones such as construction.

On my back-of-the-envelope estimate, these sectoral shifts only boosted output per worker by a quarter of a per cent or so. So at a broad sector level, the hopes of a productivity-enhancing reallocation are not borne out. But that tells us little about reallocation between companies in the same sector (and between subsectors), so the jury is still out. Free Lunch readers may already have drilled down to more detailed numbers — send any research my way.

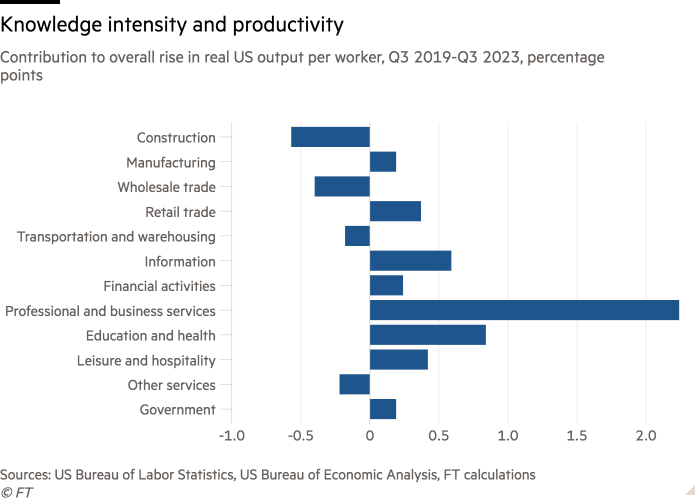

I have charted the within-sector productivity improvements (measured as output per worker) below. The biggest productivity jumps took place in information services (media, telecoms, data processing) and professional services, where real value added per worker leapt by 30 and 15 per cent respectively. Most other service sectors largely held up the all-economy productivity growth rate, with significant exceptions in wholesale trade and transportation/warehousing. These were, of course, the sectors that went on hiring sprees as the home delivery boom took off — and have clearly struggled to put their new workers to work productively.

The sector with the fastest output-per-worker growth may not, of course, be the greatest contributor to the overall productivity performance, if the sector is not very big: information services employ less than 2 per cent of workers. So the final chart shows the absolute contribution of each large sector to the US’s four-year productivity growth.

The picture is unequivocal. The productivity surge happened above all in knowledge-intensive industries: professional and business services, education and health, and information services. These are, of course, the ones that can most easily exploit remote-working technologies. They also seem to be the ones that have added the most to their physical capital stock. So investment works and markets respond to demand. Who would have thought?

Other readables

Numbers news

Billions in annual profits generated by immobilised Russian foreign exchange reserves should be used to buy weapons for Ukraine, says European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen.

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here