A private foster home operator that gave cannabis to kids in Child and Family Services care is blasting the province’s decision to break ties with the company, arguing the real issue is the lack of support for vulnerable teens who face addiction.

A CBC News investigation found Spirit Rising House was giving some foster kids in its care marijuana daily as a form of harm reduction, which was confirmed when the provincial government launched its own investigation and found unauthorized cannabis was being given to the teens.

The province said it would cut ties with the foster home operator and has asked police to investigate.

In a memo sent to staff Wednesday morning, Spirit Rising House management said they were devastated by the province’s decision, saying they cannot “express how misled we feel by all levels of government and the agencies we work with.”

“We have done our best to work inside a system fraught with denial and turning a blind eye to the trauma and real epidemic of addiction these kids face,” said the memo from executive director John Bennett.

“We did not receive proper support from guardian agencies, medical and psychiatric care, from law enforcement, from crisis supports.”

CBC’s investigation found staff were told by upper management it was better to have workers at the home provide cannabis than risk teens going elsewhere and using harder drugs, such as methamphetamine and opioids.

The Winnipeg-based for-profit company, which has been around since 2021, runs nine foster homes and two specialized group homes for 34 high-risk youth in Child and Family Services care.

The foster homes are in charge of Level 5 CFS children in care — youth with high, complex care needs deemed at risk of sexual exploitation, drug use and self-harm.

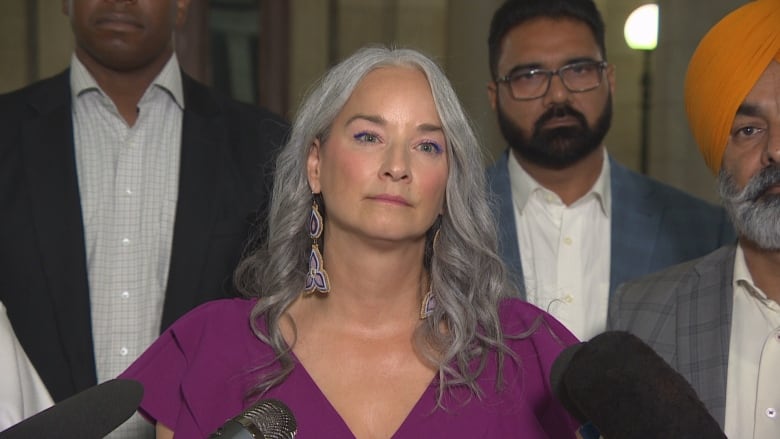

Following the province’s investigation, Families Minister Nahanni Fontaine said her department immediately stopped all placements and informed the necessary CFS agencies of the findings.

Company told of decision Tuesday

Spirit Rising House says it was told on Tuesday the province would no longer place kids in its care and the youths it is currently housing would be transitioned out of their homes. That could take months, the company said.

The memo called the province’s decision “extremely unfortunate” and argued Spirit Rising House was being publicly sacrificed, saying the failures that exist in child welfare go beyond one grassroots provider.

Bennett said the province could have worked with his company to correct the conditions and keep the youth in their homes.

“We were very open about strategies in every piece of literature we have shared with agencies,” Bennett wrote in the memo.

Bennett stressed abstinence from drug use is his company’s ultimate goal for kids in its care, but said Spirit Rising House does not shame kids if they chose to use marijuana instead of more harmful drugs.

In response to the memo, Fontaine said the province stands by its decision, stating the company took shortcuts when it came to harm reduction that put vulnerable youth at risk.

“I refuse to believe offering unprescribed drugs as a way to keep children placated is the best we can do as a province,” she said.

“It’s not good enough for my children. It’s not good enough for your children. And we can’t expect it to be good enough for any children in Manitoba.”

Kids in care need love, patience: foster mom

One longtime foster mom said while she agrees foster parents and those in charge of kids in care lack supports, she applauds the province’s decision to end its relationship with the company.

“[If] it was a harm reduction approach, maybe it should have gone through the channels of child protection services,” said Jamie Pfau, who is president of the Manitoba Foster Parent Association.

“I guarantee no social workers of these children would have approved the mode of the transactions taking place,” she said.

“I think it sends a really dangerous message when you are essentially becoming these children’s drug dealers.”

Pfau says what Level 5 kids need is a stable home, rather than a group setting like Spirit Rising House.

“They don’t need staff in and out of their lives. They need love and they need patience. And they need adults in their lives who know them very well,” she said.

Acknowledging there is a shortage of foster homes, Pfau said the government needs to invest more funds and resources to attract foster parents.

A 2019 auditor general’s report found Manitoba pays the second-lowest rates to foster parents in the country.

“It’s expensive to run a home,” said Pfau.

“Really good and well-meaning and well-intentioned foster parents are closing their homes … just because they have no support.”