We peered over the top of a perfect-looking slope — sparkling, never-skied powder snow, rolling over the shoulder of the mountain, then dropping out of sight. Dan Loutrel, my guide, stamped his skis in the snow, then dug in his poles, trying to discern any weak layers that, combined with our weight, might trigger an avalanche. He moved forwards and back, obviously weighing up a decision on whether we should go ahead and ski the slope, or retreat.

The situation was, as they say in the mountaineering world, “consequential”. He and I were alone, on a glacier, on the flank of 3,000-metre Swiss peak called the Wendenhorn. Conditions were not ideal: in the previous week, 51 people had been caught in avalanches in Switzerland; six had died.

The minutes ticked past in silence — I was anxious not to say anything that might disturb or influence Dan’s thought process — but the siren call of the slope was loud in our ears. He was clearly conflicted. Below were 500 metres of powder that, if it stayed stuck to the mountain, would provide a descent we’d remember for years. If it did slide, a crack appearing in the snow and a vast slab accelerating downwards, “Well, your angels would be working triple time,” said Dan. “And they still wouldn’t save you.”

It was the final day of a week-long adventure, a haute route through the Alps. For most anglophone skiers, that phrase means the journey from Chamonix to Zermatt, a summer itinerary devised by members of Britain’s Alpine Club in 1861, then first skied in January 1903. Now undertaken by thousands each season, it offers great views of the Alps’ most famous peaks, Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn.

But the “Chamonix-Zermatt” can feel a bit like a procession and, though it’s rarely mentioned, the skiing can be a little mundane — much of the route is made up of long, fairly level traverses.

I had come to try one of the many less-celebrated alternatives, the Urner Haute Route, a journey between the off-piste meccas of Andermatt and Engelberg in the Uri Alps of central Switzerland. It has become known as “the skier’s haute route” because it includes a succession of steep north-facing descents, is far less frequently tackled, and passes through some of the Alps’ wildest terrain. From Andermatt to Engelberg, we didn’t see another skier.

I arrived in late March, at the end of one of the warmest, driest winters on record, to find huge banks of new snow all around. A big late-season storm had just passed through — good for our prospects of powder descents but, given the meagre weak layers below, a classic recipe for avalanches. Dan was already having to rethink the itinerary, to divert us on to gentler slopes until the new snow had settled.

We met at Andermatt station, sending our suitcases unaccompanied to Engelberg, leaving us with relatively light rucksacks. We were a group of five: a honeymooning couple from the US, a father and son from Finland and me, plus two guides, Dan and a Swiss colleague, Severin (Sevi) Karrer. You don’t need to be an extreme skier to take on the Urner, but you do need to be confident off piste, relatively fit and have some touring experience.

Andermatt sits on a high plateau at the meeting point of three key Alpine passes, a strategic position controlled from the late 19th century by a major army garrison. Arriving in 1912, DH Lawrence found “the whole place was so terribly raw” that he couldn’t bear to stay the night. “Everywhere were soldiers moving about the livid, desolate waste of this upper world . . . Darkness was coming on; the straggling, inconclusive street of Andermatt looked as if it were some accident — houses, hotels, barracks, lodging-places tumbled at random as the caravan of civilization crossed this high, cold, arid bridge of the European world.”

Times have changed. Most of the soldiers are gone and over the past decade £1.3bn has been invested to create a modern, upmarket ski and golf resort, a project overseen by the Egyptian-born billionaire Samih Sawiris. A five-star hotel, the Chedi, opened in 2013. Michelin stars followed, as did new lifts and a 650-seat concert hall. Last year, Vail Resorts, the largest ski resort operator in the US, bought a controlling stake in Andermatt’s lift company; this month sees the opening of an outpost of Ibiza’s Cotton Club.

But if the jet set has arrived in Andermatt, up in the surrounding peaks and valleys things felt as rugged as ever. We began by taking a little red rack-and-pinion train out of town, a 20-minute ride up to the Oberalp Pass (and in the opposite direction to Engelberg). We stepped off the platform straight on to the snow, fixed adhesive climbing skins to our skis, and set off up a peak called the Pazolastock, Sevi setting the slow, meditative pace of an expert ski tourer. From the top we could see the cable car station on the summit of the Klein Titlis, the high point of the Engelberg ski area, only 30km away as the crow flies, but through a tangle of ridges and valleys that would take days to navigate on foot.

Dropping back down, we pressed on south into a snowbound valley that could have been Antarctica — an all-white world, snow flurries lit by shafts of sunlight through the swirling clouds. Up ahead was our objective for the night, the Maighelshütte, a lonely mountain refuge at 2,310 metres.

Inside, over hot apple cake with swirls of whipped cream, we scanned weather and avalanche forecasts, and heard more about Dan’s life story. Originally from Massachusetts, he’d come to Andermatt as a powder-chasing ski bum in 2003 and never left, first setting up a boutique ski manufacturer, Birdos, then training as a guide and starting a family.

He now speaks English with a singsong Swiss-German cadence, a joke never far from his lips. In The Last Whale in Switzerland, a short ski film released online last month, he’s asked: what lies do you tell during a working day? Without missing a beat he comes back: “That it’s going to be fun, that you’re doing a good job, and that we’re almost there.”

In the morning, we climbed up to Piz Borel, crossed the Maighels Pass, then made a 10km descent to Andermatt, passing barns on the outskirts of the village that are the winter home of yaks, the farmers finding the Himalayan animals better able than cows to cope with the local terrain.

Just to the north of Andermatt is the small town of Göschenen, the gateway to the 17km-long Gotthard motorway tunnel, a key route between Milan and Zurich that is used by some 17,000 vehicles a day. But stretching up to the west is Göscheneralp, a long, pristine valley where the sense of isolation seems sharpened by the knowledge of the rushing traffic down below.

After a short taxi ride to Göschenen, we put on our skis again to climb to Göscheneralp’s only hamlet, about 1,600 metres above sea level. It’s popular with hikers and campers in summer, but in winter the road is closed and the community cut off — fewer than a dozen people remain.

We stayed at the Gastaus Göscheneralp, a picture-perfect eight-room guesthouse with bright red shutters and a flagpole outside. Since 2016, it has been run by Dan and his wife Seraina; we were its first guests of the year. After dinner — yak stroganoff — Dan and Sevi broke the bad news: the avalanche bulletin suggested it would still be too dangerous to press on with the Urner the next day. Instead, we’d have to sit tight, take a day’s ski tour around the valley and hope for an improvement. I was anxious — making it to Engelberg was seeming increasingly unlikely.

And yet the next day dawned bright and sunny, and being marooned in Göscheneralp began to feel more like a blessing than a frustration. We ate homemade bircher muesli with fresh bread, jam from last summer’s blueberries and honey from a neighbour, then headed out to explore, skiing along the street, the occasional villager coming to their door to shout hello. Apart from the rhythmic swish of our skis, it was as still and silent as anywhere I’ve known, the snow drifts and icicles glittering.

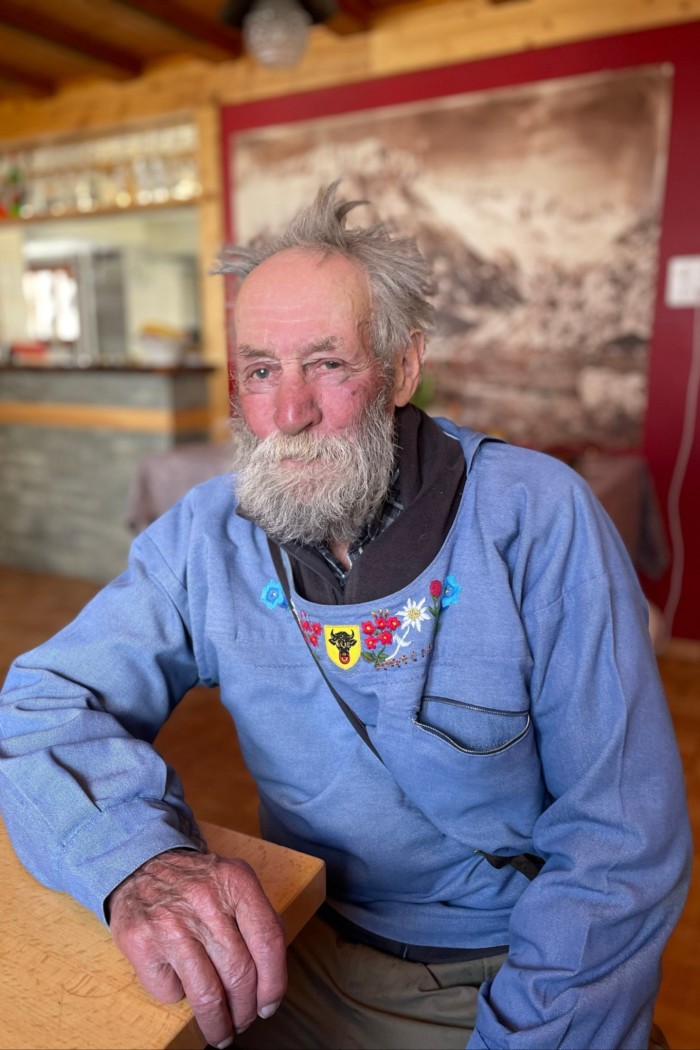

Later I had tea with Konrad Mattli, 92, who had grown up with his sister and four brothers in an older hamlet, higher up among fields on the flat valley floor. Alte Göscheneralp, a book and online oral history project, contains photographs from his childhood — as a baby on his mother’s lap, with his brothers carrying supplies through wildflower meadows on rough wooden rucksacks, and of the villagers coming together for choir practice on a chalet terrace, or for school trips to a nearby lake. “My father was a mountain guide, a hunter and a crystal collector — and we did everything together as a family,” said Konrad smiling.

The photos look pre-industrial and idyllic — no road reached here even in summer until the 1950s — but life must have been hard and people still talk about the avalanche that swept down in 1951, destroying two houses and going right through the ground floor of the school. Luckily, there were only a few children there that day, said Konrad, and so the teacher had taken them into his rooms upstairs, where it was warmer. No one was killed but after that, the families agreed to plans for a hydroelectric reservoir that was completed in 1962, submerging the old village.

That night brought more long discussions about routes and risks, then eventually a plan. If we put in a long day — an ascent of about 1,700 metres and 18km distance — we might be able to get back on track to Engelberg. We rose for breakfast at 4.30am, and clipped into our skis by the light of our headtorches. Christian Näf, the jovial goat farmer next door, had agreed to give us a tow on his snowmobile to get us up to the dam, saving us the first 40 minutes or so. He threw out a rope behind, we clung on and we were off, an unlikely trail of lights in a vast, dark valley.

By 2pm we had made it to the end of the valley and clambered over the ridge on to the dazzling expanse of the upper Stein glacier, the peak of the Sustenhorn to our right. Now it was downhill, gently at first, then steeper, the glacier cracking into a series of crevasses. We roped up to edge gingerly around them, Sevi gamely going first. It was just after 4pm when made it on to the terrace of the Berglodge Steinalp to toast a glorious, gruelling, day.

At dawn it was just Dan and me, scraping up an icy slope above the hotel. Struck down by blisters, the Finns had left us at Göscheneralp, and the honeymooners had opted for a slightly easier final day’s tour. There was no guarantee we’d make it through the last mountains to Engelberg but for now, with the sun gradually warming our backs, concentrating on the ascent and breathing hard, it was easy to be in the moment, relishing being alone on the mountain, a world away from the crowded pistes of a conventional ski trip.

At the top we could see the Titlis cable car station, but first came that slope on the Wendenhorn, and that decision.

In the end we turned back, instead choosing a much longer but gentler route down the Urat glacier, though still fabulous skiing in deep, untouched powder. On the way up to our final pass, where melting snow fell from the cliffs of Mount Titlis like waterfalls, we mulled over the choice and how appetite for risk decreases with age — “For sure, I think about my kids,” said Dan.

We said goodbye to him that night in Engelberg, which, down at 1,000 metres, was well into spring, surrounded by green fields, the verges filled with spring flowers, a shock after a week spent amid snow and ice.

The next day, with a few hours before my train, I took the cable car up to the Titlis. Inside the summit station, surrounded by year-round snow, there are cut-outs of Bollywood stars (several movies have been filmed in the area), a shop selling Lindor chocolates in numerous flavours, a prayer room, an ice-cream parlour and a photography studio complete with traditional Swiss costumes.

On the viewing platform I jostled for a space against the handrail and looked back to the shining white sweep of the Stein glacier and the steep slopes of the Wendenhorn, already finding it hard to believe how far we’d come. Then something caught my eye — a slab of snow had pulled out of the slope. I WhatsApped Dan a picture, and a thank you.

Details

Tom Robbins was a guest of Andermatt Guides (andermatt-guides.ch), the Swiss, Lucerne, Andermatt and Engelberg tourist boards (myswitzerland.com; luzern.com, andermatt.swiss and engelberg.ch) and Swiss International Air Lines (Swiss.com). The five-day Urner Haute Route with Andermatt Guides costs from SFr1,314 (£1,187)

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTWeekend on X and Instagram, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen