This article is an on-site version of our Britain after Brexit newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

Good afternoon. This week’s notable intervention in Brexitland came from European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, who told a live event in Brussels that the EU and the UK had “goofed up” over Brexit.

Here’s the full quote to Politico:

And then I must say, I keep telling my children, you have to fix it. We goofed it up. You have to fix it. So I think here, too, the direction of travel, my personal opinion is clear.

To my ears, that was a deliberately generous use of “we” by von der Leyen. She was trying to be positive, not pointing fingers but rightly crediting Rishi Sunak for doing February’s Windsor framework deal on Northern Ireland that restored relations between London and Brussels.

I also didn’t hear an EU overture for the UK to “rejoin” — as the Sun and the Telegraph did — but rather a recognition that, given this isn’t going to happen any time soon, both sides need to work harder at normalising relations in order to “fix it” — Brexit, that is.

That doesn’t mean rejoining, but taking practical steps outside institutional membership to deepen ties on climate, security, science (we have done Horizon) and perhaps most importantly the freedom for young people in the UK and Europe to travel, work and study together.

It was therefore dispiriting, in a week of diplomatic clumsiness over the Parthenon sculptures, to see how defensively Sunak reacted to von der Leyen’s remarks. He opted to soothe the Brexit-supporting press rather than open a broader conversation. After all, even David Frost has said he wants better mobility arrangements.

Instead, the prime minister’s spokesman rushed to reassure everyone the UK wouldn’t be rejoining the EU and crow (without irony) about the “benefits” of Brexit, such as controlling immigration and getting faster access to medicines.

The Sun’s leading article rehearsed hackneyed arguments about being shot of the “crumbling” EU, with Germany, a “high-polluting basket case”, at its heart, but as ever missed the main point: basket case or not, the UK has to learn to live with the EU.

Stuck in these old ruts, it looks politically impossible for Sunak to take serious steps to “fix” those damaged ties, most obviously by doing an EU-wide Youth Mobility Agreement to restore some of what Boris Johnson called the “va et vient” of daily life. (Something he lazily promised Brexit would not disrupt).

EU states are very keen for such a deal — they miss the days when EU students could attend UK universities for domestic fee rates, go easily on school trips to London or Stratford, or work a bar job in London for a summer to brush up their English.

The UK has such deals for 18-30 year olds with a host of other countries, but not its nearest neighbours in Europe, which is clearly wrong-headed — something the government has tacitly acknowledged by trying to broker such deals bilaterally with EU countries like Spain.

The Commission has headed off the UK’s attempts at brokering individual deals, convincing member states that they will get a better outcome by sticking together, negating what they see as a British play to attract young EU labour, selectively, and on the cheap.

It has therefore begun to “scope out” — as one official puts it — what an EU-wide UK mobility deal might look like, but has found a nervous partner in London that has warned that the UK political climate on immigration makes any such deal very tricky.

Indeed. But this government has had a hand in creating such an atmosphere, lionising the UK’s research universities and the “science superpower” in one breath, yet in the next attacking the international students that in effect fund the higher education sector.

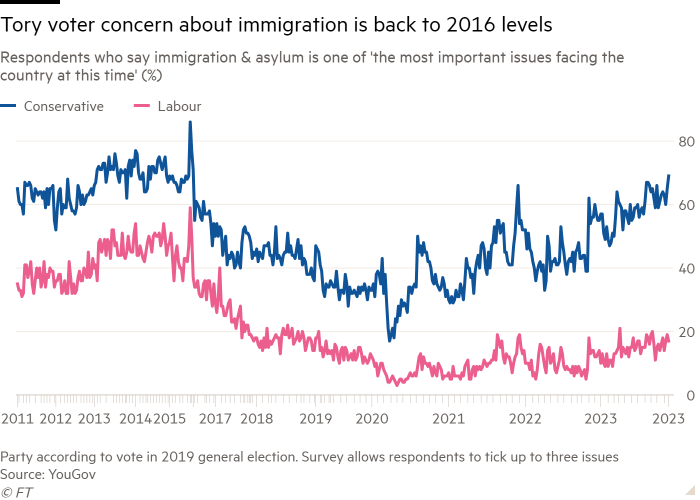

The Commission is apolitical about the colour of the UK government with which it concludes an EU-wide mobility deal. But a Labour administration should have more political space (see today’s chart, below) with which to make an EU-wide agreement.

That doesn’t mean it will be easy. Von der Leyen speaks in sweeping terms about repairing Brexit for the next generation, but the nitty-gritty of the discussion will not be without hurdles for Labour.

Talking to EU diplomats, I’m struck by how ambitious their mobility shopping list is — not just rejoining Erasmus+, the student exchange scheme, but also returning to the days when EU students paid “home fees” and could access student loans, as well as reciprocal routes for trainees and apprentices.

Rejoining the next round of Erasmus negotiations in 2027 makes sense, but Labour ministers can expect to encounter the same Treasury objections that torpedoed any prospect of the UK taking up post-Brexit Erasmus membership during the 2020 negotiations.

The fact that Erasmus saw 35,000 EU higher eduction students coming to the UK — but only about half that number going the other way — meant that the net “cost” to the UK exchequer from its £600mn contribution was around £350mn-£400mn.

The UK has “saved” itself some money, but at the cost of loosening ties with the neighbourhood and exacerbating the UK’s very poor record in teaching and speaking foreign languages.

Rejoining Erasmus might therefore be a price worth paying in order for Sir Keir Starmer to demonstrate his commitment to the wider EU neighbourhood, but you can also see how a Tory party in opposition might make mischief with subsidising EU students. Bravery will be required.

Returning to “home fees” for students and reciprocal exchange for apprentices will be much harder.

Given that UK universities are projected, per Russell Group analysis, to make a £4,000 “loss” on each UK student paying the £9,250 tuition fee by 2024/25, you can see how the sector is going to struggle with welcoming back EU students on those lossmaking terms.

UK universities have seen the annual intake of EU students halved since Brexit, falling from about 67,000 to 31,000 a year — something many university vice-chancellors regret.

But at a time when international students are providing vital financial subsidy to the sector, returning to “home fees” — something that cost the UK treasury about £500mn a year in student loan costs — would be a very big ask from the EU side.

Similarly, a reciprocal route on apprentices is also tricky, since any “special visa” regime risks creating a layer of bureaucracy that becomes self-defeating, as the point of such a scheme is for trainees to easily do placements in each others’ countries.

To be clear, none of this is an argument for not doing a youth mobility deal. One of the silliest underlying conceits of the current Brexit deal is that Europe should be treated identically to any other country, however distant. Size and proximity matter.

A future British government less hamstrung by anti-immigration politics of its own making should engage swiftly with Brussels to make it happen, but both sides need to be realistic about the finances and complexities and avoid negotiations sinking back into acrimony.

First and foremost, that means creating an atmosphere of trust where such negotiations don’t become zero-sum games. Von der Leyen seemed to be trying to speak to that goal. It’s a shame that Sunak, despite the Windsor framework, was unable to embrace it.

Brexit in numbers

This week’s chart is a real fascinator that comes courtesy of Alan Wager at the Tony Blair institute. It shows how sharply attitudes to migration among Tory and Labour voters have diverged since the Brexit deal came into force.

Concerns over migration levels between Labour and Tory voters have ebbed and flowed over the years, but those concerns (while consistently more elevated among Tories) have always broadly shadowed each other. Until 2021.

During the first two post-Brexit years in which the UK introduced a points-based immigration system, net migration has hit a record 745,000 in 2022, raising questions among many Brexiters about whether referendum promises to “take back control” are being fulfilled.

This has also coincided with a rise in cross-channel migration (but much smaller numbers, with 45,000 crossings in 2022), which has led Tory ministers to fixate on repeatedly promising to ‘stop the boats’.

Unfortunately the serious policy responses (reducing claim backlogs, deals with EU Frontex) have received less attention than the performative ones, like offshoring asylum claims to Rwanda, which have failed to deliver, and brought ministers into conflict with both UK courts and international law.

As Rob Ford at Manchester University pointed out in his Sir Roger Jowell Memorial Lecture this hardening of Tory attitudes to immigration runs contrary to the broader trend of UK voters taking an increasingly liberal attitude to migration over the past decade or so.

Wager posits that the more recent divergence in UK public attitudes is linked in part to the ending of free movement, which had the effect of defanging the immigration issue politically for the majority, even as it continues to exercise the right.

Ending free movement, he surmises, has created overall space for a more nuanced understanding of migration among most people: swing voters actively differentiate between the relative merits of asylum seekers, social care workers and students, for example.

This new dichotomy presents a challenge for Sunak trying to protect his right flank from the Farage-founded Reform UK party, but also potential room for Starmer to maintain a liberal immigration policy for the sake of the economy, including a youth mobility agreement with the EU.

As Wager puts it: “The politics of immigration has reversed. Previously the Conservative party’s ace card, it has become a party management headache for Sunak. Meanwhile, the data on overall attitudes to levels of migration and support for migrants in key sectors creates space for a more nuanced approach from a future Labour government.”

Britain after Brexit is edited by Georgina Quach today. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Inside Politics — Follow what you need to know in UK politics. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here