Frontline health leaders are bracing for one of the NHS’s toughest winters as FT analysis of official data shows it entering the season with a deep gulf between demand and supply, threatening to put emergency services under intense pressure for the second year running.

Months after the government sought to take control of the crisis in the service by publishing an urgent and emergency care recovery plan, general and acute bed occupancy levels — a key barometer for strains on the system — remain far above levels many clinicians consider safe, and large numbers of patients are still waiting more than 12 hours for emergency treatment.

Strikes by consultants and junior doctors, who walked out for three days this week, have added an additional element to the cocktail of pressures that the NHS faces over the winter, such as rising rates of chronic respiratory illnesses, and infections such as flu, norovirus and, in recent years, Covid-19.

The strains point to the difficulties Rishi Sunak, prime minister, will face in meeting his pledge that waiting lists for non-urgent care should be falling by the next general election, expected in 2024. They have risen by about 500,000 since he made this one of his “people’s priorities” in January.

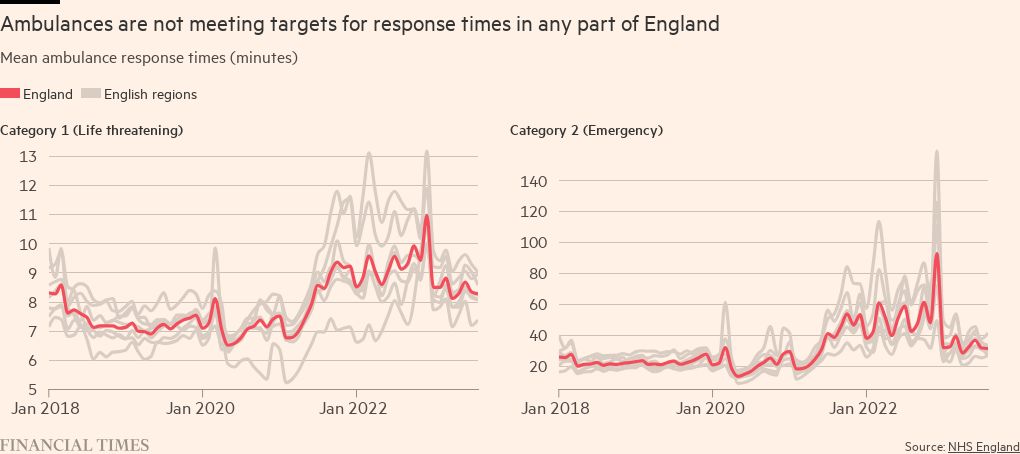

The NHS last year experienced near-unprecedented pressures last winter, with ambulance response times among the worst on record for the two most urgent categories of callouts. While these have improved from their nadir in December, they have since remained relatively flat and are still far above both pre-2021 levels and the healthcare service’s targets.

Adrian Boyle, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, warned: “The system is quite fragile and could fall over very badly, in the way we saw last year.”

Continued industrial action will make it even more difficult to tackle the delays. About 2,000 medics protested against the government’s refusal to negotiate over doctors’ pay at a rally close to the Tory party conference venue on Tuesday. Earlier Steve Barclay, health and social care secretary, said striking doctors posed “a serious threat to the NHS’s recovery from the pandemic”.

Mike Greenhalgh, deputy chair of the junior doctors’ branch of the British Medical Association, said Barclay’s claims were “frankly disingenuous” when his government had refused to negotiate with the union or present a credible pay offer for several months.

Matthew Taylor, chief executive of the NHS Confederation, said: “By the time we reach the deep winter months, the NHS will have experienced nearly a full year of industrial action.”

He added that while the government had announced earlier this year that it would provide winter-specific funding, “it pales into insignificance compared with the cost of ongoing strikes”, which is now estimated at £1.3bn.

In an apparent bright spot, Boyle said the length of time ambulances had to wait outside hospitals to decant their patients had fallen, suggesting some bottlenecks in emergency departments had eased. However, he suggested this had been achieved by increasing the number of patients being treated in corridors.

Boyle added there was little change in the high number waiting at least 12 hours for treatment once they arrived at A&E. “That number has stayed pretty constant over the summer — about 100,000 people each month are staying more than 12 hours,” he said.

In addition, the college’s own calculations had found that roughly 400,000 people had spent more than 24 hours in an A&E department in 2022-23, a length of stay he considered “unconscionable”.

The numbers involved were equivalent to “at least three-quarters, sometimes a whole medical ward, lodged in an emergency department”, Boyle said.

Warning that the fundamental problem in the NHS was a shortage of beds, he said it was “perfectly possible we could end up with the same problems that we saw last December and January”. Those months saw exceptional pressure on emergency services with a record number of 999 calls and ambulance callouts for the most serious emergencies.

Lack of social care provision has further added to pressure on bed availability. Across the country about 13,000 people were stuck in hospital waiting for some form of social care: “over 10 per cent of the bed base”, according to Boyle.

In its urgent and emergency care plan, published in January, the government promised an additional 5,000 beds in England for this winter, along with 800 new ambulances but health leaders are concerned that the additional beds may not be delivered in time to make a difference.

Some hospitals were also coming under pressure from cash-strapped integrated care boards, which plan and fund care for their local areas, to close so-called “escalation beds” — the temporary beds opened to cope with a surge in demand — in order to cut costs.

Funding issues have become a wider problem for the service, according to Siva Anandaciva, chief analyst at the King’s Fund. He said conversations with clinical and financial directors suggested that the NHS’s finances were “deteriorating really rapidly”.

NHS England has said “virtual beds” in which patients are monitored at home, ensuring they can be sent home earlier or do not need to be admitted at all, will help it treat more patients with current resources.

Among hospitals pioneering ‘virtual beds’ is West Hertfordshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, which on average cares for 100 patients a day remotely, freeing up the equivalent of two hospital wards, noted Matthew Coats, chief executive.

He argued that if expanded across the country as health leaders hope, the approach could be “a game-changer” for the NHS, releasing much-needed capacity to treat the most seriously ill in hospital. The initiative, delivered in collaboration with community nursing staff, and backed by the local authority, had contributed to a 20 per cent reduction in delayed discharges in the past year, he added.

But the Confederation’s Taylor said while virtual wards “undoubtedly have an important role to play . . . in and of themselves [they] don’t provide the solution — they still require staffing and capacity in the community” which remained “a significant challenge”.

He urged the government “to be bold” to break the cycle of the health service’s annual winter crises. This would mean “shifting resource and focus to out-of-hospital settings” and ensuring people could be cared for as close to home as possible, he said.

He added that the health service also needed capital investment to tackle an £11bn maintenance backlog, as well as funding to deliver the commitments in the NHS’s long-term workforce plan, published earlier this year.

The Department of Health and Social Care said. “We have started preparing for winter earlier than ever before to ensure patients can access the care they need.”

It added: “We are creating 5,000 permanent staffed hospital beds . . . and the NHS England’s urgent and emergency care recovery plan has seen improvements made in both A&E waits and ambulance response times compared to last year.”

The NHS said while recent data “clearly shows the pressures facing NHS staff”, it also showed measures in the urgent and emergency recovery plan “are starting to drive real improvements despite record demand”.

A total of 73 per cent of patients were seen in accident and emergency within four hours in August, up from 69 per cent in December, and responses to so-called “category two” ambulance call outs — which can include suspected heart attacks and strokes — were more than an hour faster than at the start of the year, added the NHS.