A year ago, UK brickmakers could not produce enough to keep up with racing demand. Now, they have the opposite problem: brickyards are not big enough to hold the mounting stacks of unsold stock.

With high interest rates putting many housebuilding projects on hold “for the foreseeable future”, Forterra, a listed brickmaker, is cutting manpower and mothballing sites — including one, in Lancashire, where a gravity-fed ropeway has carried clay to the kilns for a century.

“These are good, well-paid, unionised jobs,” said Charlotte Childs, a national officer at the GMB union. About 200 staff will be affected, including many in roles such as kiln or machine operators that would typically attract salaries above £35,000.

The construction sector — hit by the housing market downturn, squeezed mortgage holders scrapping home extensions and the potential scaling- back of big public projects such as the HS2 rail line — is bearing the brunt of a wider labour market slowdown.

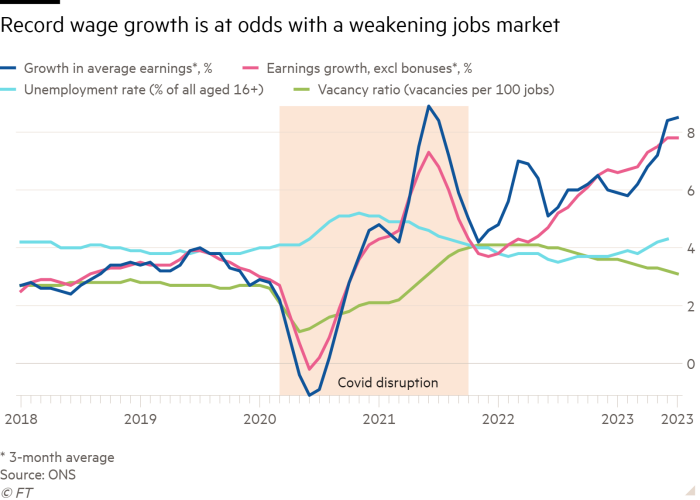

Vacancies, which rocketed in the post-coronavirus pandemic upswing, have been falling for more than a year. The latest official data showed unemployment up sharply from 3.8 per cent on the quarter to 4.3 per cent and employment down, even though average wages were still rising at a record pace.

But these figures only cover the period up to July and analysts have questioned whether they can be relied on — as the Office for National Statistics is in the process of overhauling its labour market survey following a sharp drop in response rates since the pandemic.

Gauging just how much the jobs market has weakened since the summer is crucial for policymakers at the Bank of England as they assess how long to keep interest rates high. The monetary policy committee thinks unemployment will have to rise, and wage growth slow, for inflation to return sustainably to its 2 per cent target. But if it keeps policy too tight for too long, it could trigger unnecessary and painful job losses.

With banks, law firms and consultancies seeing a drop in mergers and acquisitions; big tech companies scaling back their presence in the UK and consumer-facing industries feeling the effects of squeezed household budgets, jobseekers are now in a very different environment than in 2021 and 2022, when employers entered bidding wars to fill gaps.

“People coming back from the holidays are putting their heads down, staying put and are just thankful they have a job,” said Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG, who has found employers around the UK to be much less concerned about staff churn and wage pressures.

Others also said the labour market could now be weaker — and wage growth slower — than the official data suggested.

“We are in a different place from 12 months ago . . . [Employees feel that] if you have a record and tenure, maybe it’s better to stay where you are,” said Chris Gray, director at the recruiter ManpowerGroup UK, describing the overall jobs market as mixed, with variation between sectors, but “probably more ebb than flow”.

However, most analysts think that while wage growth is slowing, job losses are likely to be more limited than in previous downturns — because the UK workforce is already depleted by demographics, the departure of EU workers and high rates of long-term sickness.

Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment & Employment Confederation, said that although employers were taking longer to commit to new hires, confidence was nevertheless improving. “The impact of a long period of slow growth is less than it would have been in the past,” he said, adding that many companies would be able to attract candidates on lower salaries if they were willing to continue offering flexibility on homeworking.

The benign overall picture masks big differences between sectors, with construction and retail suffering, while areas such as social care still struggle to recruit. But even in sectors that have seen high-profile lay-offs, recruiters say there are still pockets of strong demand.

Rhona Carmichael, chief commercial officer at the specialist tech recruiter Nash Squared, said many regional companies had been unable to compete on pay at the height of the post-Covid hiring frenzy, as remote working allowed the US groups to recruit from a wider pool.

“They were getting gazumped when the market was out of control . . . Now there is a degree of normality,” she said, adding that more than half of companies still aimed to expand IT teams.

As workers become more wary of leaving a secure job, some recruiters say they are in a paradoxical situation where employers are not looking to add to headcount, but are still struggling to keep staffing at full strength.

Gray said that although job ads were now attracting more applicants, it was “like walking through treacle”, with businesses constantly recruiting to replace staff who left or fell ill, rather than to expand.

Even in the sectors hardest hit, industry figures worry more about struggling to recruit when demand bounces back than they do about job losses now.

Greg Shaw, a regional director for Randstad’s construction team, said the recruitment agency was looking to fill just 350 vacancies in the sector, down from 1,850 a year ago, and that there was a big risk skilled workers would “melt away into the rest of the UK economy” during the downturn.

“The government has to act now before people start drifting away into different industries,” he said, arguing that work to fix unsafe school buildings could help use slack in the sector.

Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association, said the sector’s workforce had shrunk by 273,000 since 2019, due to early retirement among the self-employed, EU workers leaving and the more recent downturn. This would make it impossible for the government to hit its goals on building affordable housing, making existing housing more energy-efficient or levelling up, he argued.

“Once you lose workers to early retirement or other sectors, they don’t tend to come back.”