Dolores Naponse keeps a binder filled with memories both good and bad.

There are baby photos of her granddaughter Jayde, whom Dolores is proud to see own and operate an Ottawa cafe at Lansdowne Park alongside Dolores’ daughter Paula.

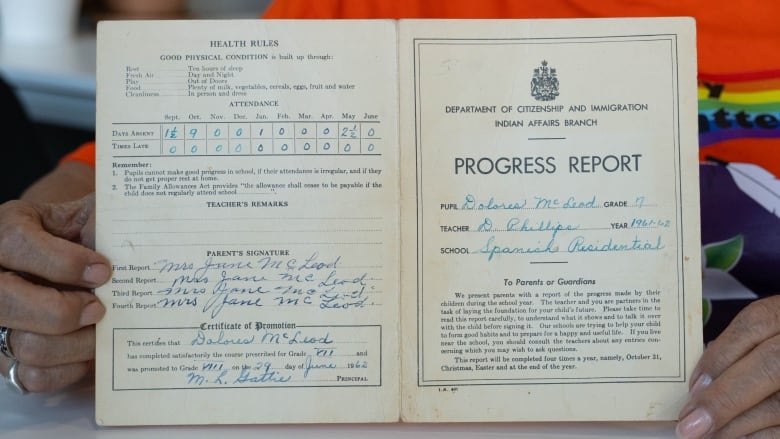

But there’s also a report card Dolores saved from her time at Spanish Girls School, a residential school south of the Naponse family’s Sudbury-area reserve, Atikameksheng Anishnawbek First Nation.

A tearful Dolores, 11 at the time, was bused to the school in 1959, not long after her mother had died. Dolores’ grandmother, who took over raising her, believed Dolores would get a proper education at the school.

Instead, she was lonely and “the [Anishinaabemowin] language was thrown out,” Dolores said.

Major Christian denominations operated federally funded residential schools in Canada beginning in the late 19th century. Separated from their communities and families, children were then subjected to various forms of neglect and abuse.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Spanish Girls School students were more involved in farm labour than at other residential schools, though, like other schools, overcrowding was a problem there too.

Many suffered even worse fates across the system. The centre estimates at least 4,100 children died at residential schools. The true number is likely much higher, according to Murray Sinclair, the former chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The effects of Dolores’ time at the school have been felt by her family for decades.

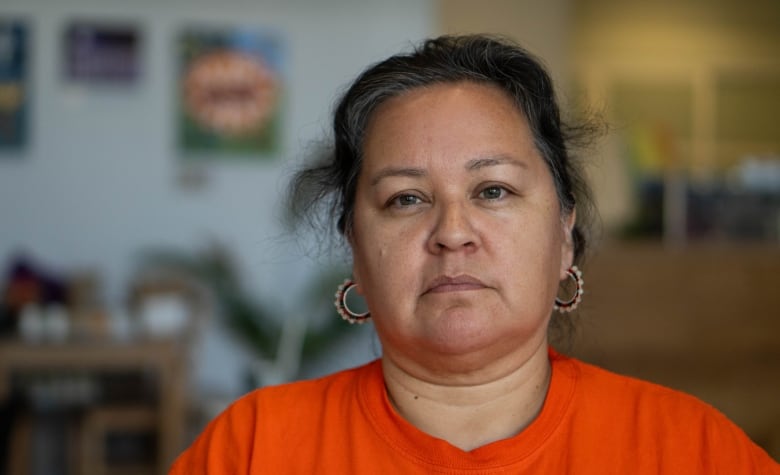

On Friday, the day before Canada’s third National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Dolores, Paula and Jayde spoke from the cafe about their experience of intergenerational trauma, their hopes for ongoing reconciliation — and the mix of commitment and exhaustion they feel due to the demands placed on them in the leadup to Saturday.

Dolores

Dolores’ aunt was also sent to Spanish Girls School. Her aunt ran away, only to be taken back by police, Dolores recalled.

When Dolores questioned why she had to go to the school too, she wondered: “Am I a bad girl?”

“That’s what I was thinking in my little head,” Dolores said.

Dolores “lost all confidence” in herself coming out of the school. She began drinking when she was 14 as a means of coping.

The birth of her granddaughter Jayde was a turning point.

“[Jayde] made me quit because I saw her as a little girl and I said ‘I don’t want her to live that kind of life,'” Dolores said. “I wanted to live for her.”

Dolores got her university degree and became a speaker about her time at residential school. She also pushed her children — including Paula, Jayde’s mother — to seek the education she was initially denied.

“I always encourage them to move and do something, but a lot of times we get lost in it all too. We have to be aware of how we were treated and….have to change ourselves on that thinking in our heads that ‘I’m no good.'”

While Dolores mentioned going to Spanish Girls School, it wasn’t until Paula attended university herself, and learned about the residential school system, that she realized what her mother went through.

Paula

Hearing about her mother’s experience has been a journey, Paula said. She’s still learning new things.

Asked how intergenerational trauma has manifested itself, Paula said the family’s parenting skills were affected, citing feelings of anger and depression.

“You go do other things besides telling people what you feel,” Paula said. “You may go into the room and shut the door instead of actually talking to people and telling them what’s going on.”

“Those are things that I’ve carried with me,” she added.

The owners of an Ottawa cafe say the necessary work of educating the public about Canada’s history with residential schools weighs heavily on families still struggling with generational trauma.

On Saturday at 12 p.m., the family is inviting the general public to Beandigen Cafe, which Paula and Jayde opened in 2021, to learn about Dolores’ first-hand experience of residential school.

“I want to show you this because this is proof I went there,” Dolores said on Friday, pointing to her report card. “This is not a made-up story. This is true. And denial is very strong in our cities and even in [Sudbury].”

Paula agreed the ongoing work of educating the public is vital, but added it comes with a cost to those at the centre of the story.

“A lot of these interviews we have to do, we want to do [them] and we love to do [them] and we love to tell our stories,” she said.

“But it’s exhausting. It’s really exhausting.”

Jayde

As the co-owner of a prominent business, Jayde said she also feels that pressure — even though Indigenous people have been commemorating survivors for decades.

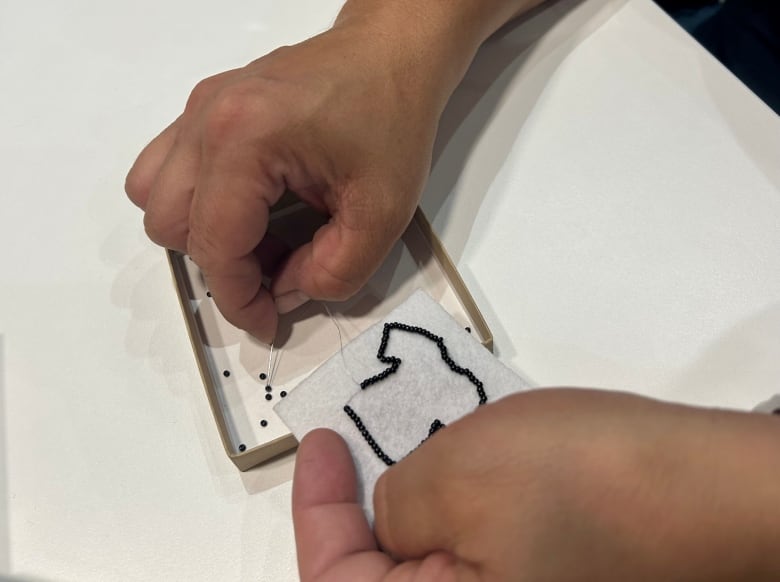

Jayde recently hosted two workshops at the cafe to teach people how to bead orange T-shirt pins. A mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people attended each session, with Jayde encouraging discussions on the ongoing effects of residential schools.

“It’s really important to have a face-to-face, person-to-person interaction that really brings it into focus for people [that the] things that happened at these schools were not to imaginary people that you’ll never meet,” Jayde said of the workshops and Saturday’s talk with Dolores.

“There are people in our communities that have dealt with this and their family members that are still dealing with a lot of the after-effects.”

The aim of the workshops was also to highlight the talent of Indigenous people — “not only the trauma that we’ve dealt with, but the good things and the happy things,” Jayde added.

Jayde said much still needs to be done to inform people not just about residential schools but the longer list of injustices perpetrated against Indigenous people, including the Sixties Scoop, the forced sterilization of women, and the ongoing search for justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Jayde cited the growing calls for a committed search for missing First Nations women’s bodies at a Winnipeg-area landfill as a more recent concern that’s top of mind as Canada marks its third truth and reconciliation day.

“That’s really important to be able to bring that respect to those people that are suffering,” she said. “It’s not just Winnipeg. It’s every single First Nations community.”

Ottawa Morning12:56Three generations of the Naponse family talk about the impact of residential schools

Residential school survivor Dolores Naponse shares her experience and her daughter Paula and granddaughter Jayde join the conversation. They’re inviting people to pull up a chair at their Beandigen Cafe and listen on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

After Saturday’s talk featuring Dolores, the family will take a breather and attend the Ottawa Redblacks game just steps away at TD Place — Paula’s first time seeing the team.

The family enjoyed a similar respite during last year’s truth and reconciliation day when Dolores got to throw the first pitch during a Toronto Blue Jays game.

“That was probably one of the best experiences for all of us,” Paula said. “She was down on the field with my two little boys. It was so fun, such a celebration. We love doing those things, but we don’t get a chance all the time.”