Receive free UK economy updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest UK economy news every morning.

It’s a testament to the kind of 12 months the Bank of England has had that this is the second time we’ve recently used “squeaky bum time” in a heading.

When the Monetary Policy Committee takes its next rates decision on September 21st, it will mark almost exactly a year since the mini-Budget spawned one of our favourite-ever Wikipedia article tops:

It’s fair to say things have been moderately calmer since then, if not altogether more comfortable: a string of inflation overshoots have kept pressure on the MPC (while offering a bit of relief on the currency side).

Now, after 14 consecutive hikes, the end might finally be in sight. As Governor Andrew Bailey told MPs yesterday:

There was a period where it seems to me it was clear that rates needed to rise . . . and the question for us was how much and over what timeframe, but we’re not I think in that phase any more

I think we are much nearer now to the top of the [interest rate] cycle.

Markets seem to tentatively agree — at pixel time they were pricing in a roughly 80 per cent chance of a 25bps hike based on Bloomberg’s WIRP estimates:

…which indicates it’s September and then done.

The data context is interesting. Last Friday’s narrative-shifting Office for National Statistics GDP data revision has changed everything, and nothing.

Very amusing handwringing at the Treasury Committee with MPC members bemoaning not knowing at the time GDP would be revised up…

SHORT MEMORIES

It was higher at the time – was revised down and then up again. They had the right data (roughly) at the time

— Chris Giles (@ChrisGiles_) September 6, 2023

Based on what we’ve seen from the sellside since, there’s a general satisfaction that growth and the strong labour market are finally aligned, combined with a repeated warning: the (re) discovery of historic growth just means the present outlook is even more meh.

As TS Lombard’s Konstantinos Venetis puts it:

…the positive output “level effect” does not translate into a commensurate boost to the tax take and therefore does not make the UK’s increasingly difficult fiscal arithmetic any easier as the prospect of “high(er) for longer” interest rates exposes the public sector’s rising debt burden.

Nor does it alter what is a souring cyclical picture: the economy is losing momentum and real GDP is set to flatline this year as the lagged impact of this BoE hiking cycle inevitably starts to bite.

Recent PMI surveys have solidified the sense that the slope into contraction may finally have arrived:

It’s still pretty touch-and-go. Nomura’s economists, who are now calling a eurozone recession, see only a 40 per cent chance of the UK suffering the same fate. They write [our paragraph breaks]:

What could make the UK different? On the whole a number of factors mean the UK could be slightly better off, relative to the euro area:

(1) maybe most importantly, the BoE Credit Conditions Survey shows much more resilience for both firms and households in face of the UK monetary policy tightening cycle, with firm demand for lending reportedly barely hit.

(2) Excess savings in the UK are more elevated, meaning households could have a stronger buffer in face of the impact from higher rates. However, it is true that these savings could be in the hands of higher income groups with lower marginal propensities to consume.

(3) Private sector regular wage growth in the UK is much higher, potentially supporting consumption more.

(4) The UK’s budget outcomes of late have proved better than expected, and the UK government, ahead of a likely general election next year, has a more concrete fiscal loosening plan, versus in the euro area, where there remains a lot of uncertainty over the timing of disbursement and use of NGEU funding.

(5) Despite recent upward revisions to UK GDP growth during the pandemic, the UK’s post-pandemic performance remains weaker than many of its peers, suggesting UK GDP has greater potential to still catch-up.

(6) And finally, on a historical basis, the UK economy has tended to grow at a stronger rate than that of the euro area.

Weighing against these positives are the scale of tightening that has occurred, the UK’s higher inflation, the bigger apparent hit to the UK labour market from tightening and, of course, Brexit.

With this kind of backdrop, the MPC’s next move looks delicately balanced. If sterling is on the way down, that may sustain inflationary pressures longer than is currently expected, but sterling might be . . . OK? Here’s Rabobank’s Jane Foley:

Although it remains the case that UK data are far from strong, it has become plain that the UK economy has significantly outdone the forecasts that were prevalent last year.

A split is a certainty because of Swati Dhingra (whose annual report to the Treasury select committee, released yesterday, reads quite tragically). But Huw Pill and Ben Broadbent, both better bellwethers, have both given recent speeches in which they sounded relatively hawkish.

After all, there are reasons to be more positive about the UK’s economy outlook. Here’s Berenberg’s Kallum Pickering in a note published today:

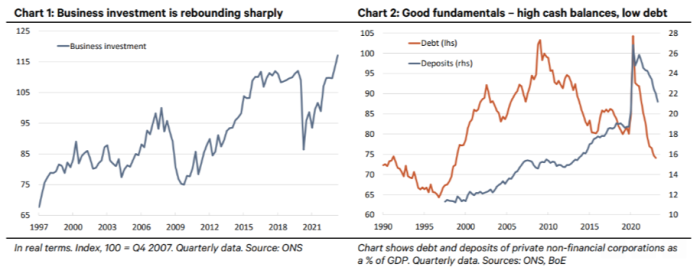

In sharp contrast to the general mood of gloom hanging over the UK economy, businesses are growing capital expenditure at a rapid pace. Business investment had slumped in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC) and then stalled after the Brexit vote amid paralysing political uncertainty. It then suffered another big hit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Weak capital investment hampers productivity, restrains supply potential and contributes to cost-push inflation.

But the situation is improving. As Chart 1 shows, business investment has surged by 35% from its Q2 2020 low. By Q2 2023 it was 6% above its pre-Brexit-vote high. Although the rebound cannot offset the costs of the post-2016 investment shortfall, capital spending is now back on its pre-GFC trend. With luck, the rebound to the old trend may be a sign that the UK’s growth potential is picking up after six years of deterioration.

Somewhat ironically, Pickering notes that one of the factors that could disrupt this positive trend concern about a recession — in other words, that UK growth might be in a “nothing to fear but fear itself” stage.

It’s yet another unenviable position for Bailey and the gang, who could be vindicated by their decisions — or damned by them — in the months ahead.

Given the circumstances, we think it’s pretty likely that the MPC will park the bus this month: go defensive with one last 25bps, then wait for this whole thing to blow over.

Further reading

— Some pointless charts about the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee