One flyer proposes building “a community of women” to create “alternatives to patriarchy.”

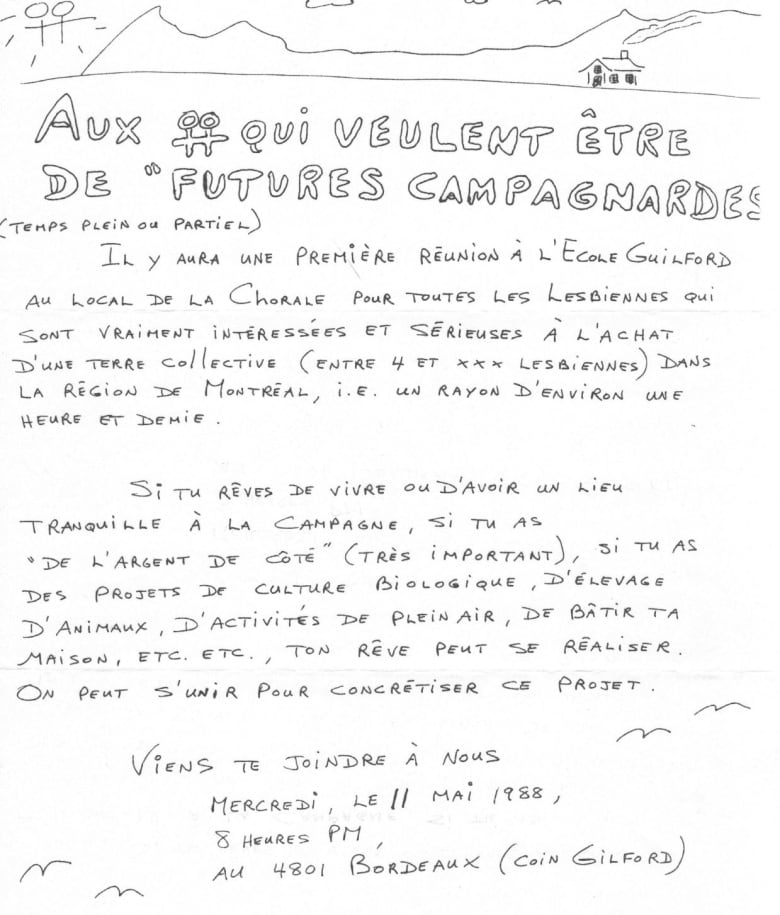

Another suggests “future country girls” attend a meeting in the Gilford School’s choir room if they’re interested in “buying collective land in the Montreal area.”

As early as 1981, communes owned and operated by lesbians have existed in rural Quebec — and some still exist today.

And it’s no coincidence these flyers for what became known as lesbian lands advertised meetings at the Gilford School.

Between 1985 and 1996, a group of lesbians leased the Plateau-Mont-Royal school and ran it as a community centre with a lesbian choir, self-defence courses, dances and other activities.

The school was also home to the Lesbian Archives of Quebec, which documents the history of lesbian life in the province.

Most Montrealers would never know these stories if it wasn’t for the archives, as queer history — especially queer women’s history — isn’t part of mainstream education.

Laure Neuville, the archives’ only paid employee, became interested in the Lesbian Archives of Quebec while studying lesbian authors in the ’90s. But she didn’t find the archives until much later.

“We hear about Sappho, Gertrude Stein, all these famous artists and writers, but what about ordinary lesbians in Quebec? Who were they, how did they live?” said Neuville.

“When you’re madame tout le monde it’s not always simple.”

Shedding light on hidden history

Archivists spend hours upon hours searching for traces of lesbian history through coded language or hidden stories in old documents. Many stories about homosexuality still aren’t indexed as such, like a wedding between two women in 1942.

Women passed themselves off as men during the Second World War to work in factories and earn a man’s wage — which was much higher than a woman’s — and in Sainte-Thérèse, Que., one such woman got married to another female colleague.

Six months after the wedding, her wife came out publicly and denounced their marriage as a sham, exposing her “husband” as a woman, who was then pursued in court for identity fraud.

“We aren’t sure how the story ended. There aren’t archives of the verdict,” said Neuville.

“All the big newspapers like La Presse were reporting on it at the time, but it was never written ‘two lesbians’ or ‘lesbian wedding in Sainte-Thérèse in 1942.’ When you’re doing research, you have to look at all the newspapers of that year and happen to stumble on the stories.”

Women’s history has long been suppressed, said Neuville, even more so for those marginalized like racialized, working-class and queer women. She said the first real studies of women’s history started in the 1960s, and gender studies only started being seen as a legitimate field in universities in the 1990s.

Neuville pointed out that it was once very difficult to live as an independent woman. They couldn’t have their own bank account or sign a lease until the ’60s — nevermind live with another woman when homosexuality was criminalized.

Even in feminist movements, lesbians often stayed in the closet as their sexuality was seen as a threat to the movement’s image, said Neuville, making it hard to track them.

“There were others before us and they succeeded in conditions that are more complicated than ours to survive and create a community, be in a couple, start a family even,” said Neuville.

“It helps us find our identity but it also helps us reflect on our current struggle and strategies for queer liberation.”

From basement to basement

The lesbian archives got their start at La Kahéna restaurant in 1983, when the women running it started collecting documents. They later moved to the Gilford School.

But when the school was turned into a co-op in the ’90s, the archives were kept in various lesbians’ homes.

They were dormant until the Montreal LGBTQ+ Community Centre gave them a room — “more like a closet,” said Neuville — to keep the boxes.

“This is pretty typical for queer archives,” said Julie Podmore, an LGBT researcher who sits on the archives’ board of directors.

For one, it’s often difficult to find institutional space and secure funding for an archive, she said.

“And then there’s that tension, of course, with not wanting to give it over to institutions like universities or libraries and to keep it within the community,” said Podmore.

The Lesbian Archives of Quebec have a lot of typical archival materials like posters, news clippings, old magazines and videos but also unconventional items like clothes, banners, buttons and other cultural artifacts.

Almost every copy of the Quebec lesbian magazine Treize — of which Neuville was once editor-in-chief — are kept in neatly labelled boxes, along with other publications and scrapbooks full of posters.

Last spring, the archives moved to the Cité-des-Hospitalières monastery right by Jeanne-Mance Park.

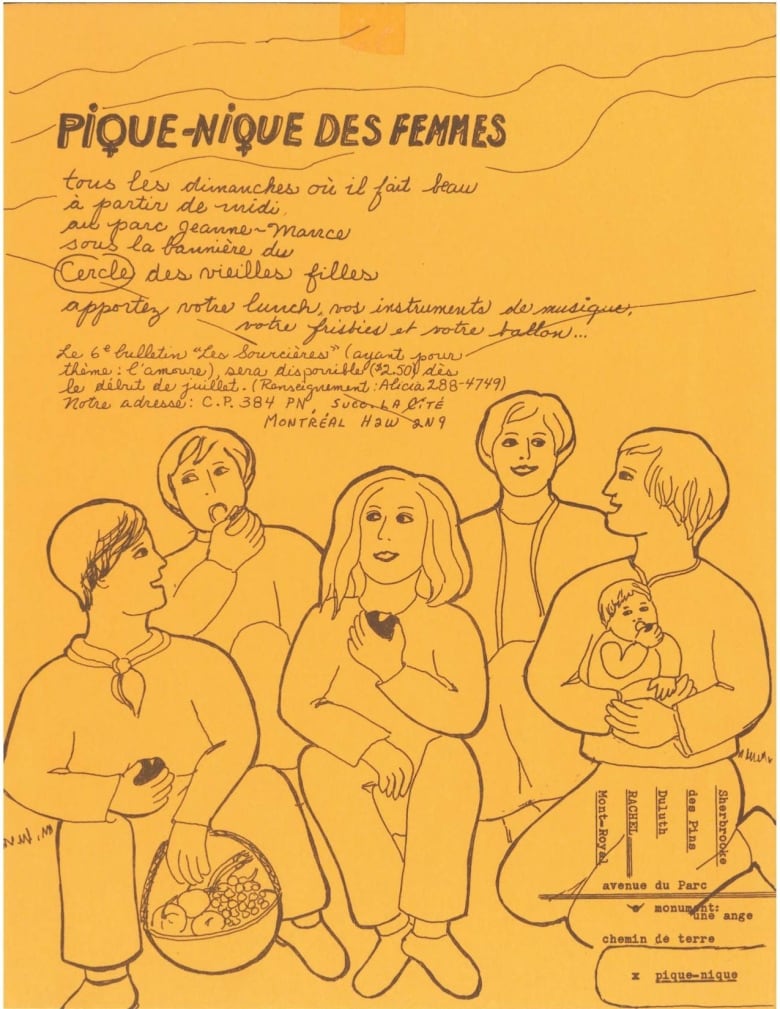

“It’s funny to be near Jeanne-Mance Park, considering its history,” said Neuville.

Many lesbians lived in the Plateau-Mont-Royal area in the ’80s — where the city’s first lesbian bars opened, all of which have since closed — and would have picnics at the park every Sunday.

Posters would be pasted around the city that included a small map to find the group that would gather under a banner for le cercle des vieilles filles (the circle of old girls).

Passing on knowledge

Now that the archives have found a proper home, Podmore said the collective wants to work on more community initiatives. It now offers internships for library and archiving students and welcomes researchers, for example.

“That’s what we really want to do, because I think community-based archives need a community to support them and to make them relevant,” said Podmore.

Neuville and volunteers are working on indexing and digitizing the archives — though most won’t go online due to copyright and privacy concerns.

They also hope to incorporate the archives, develop protocols to acquire new material and continue receiving operating grants.

Neuville and Podmore want the next generation of queer people who identify with the lesbian experience to have access to these historical materials, feel connected to those who came before them and maintain a continuity of activism in the community.

“Queer history is not mainstream.… We don’t know stories about things like Sex Garage or the Gilford School. And that’s because, of course, queer history has been marginalized from mainstream history, like a lot of other histories,” said Podmore.

Neuville agrees.

“I would like for younger lesbians to not have to reinvent the wheel with every generation.… That’s not to say that we shouldn’t keep reflecting and evolving with time, but there’s something important in not starting at square one,” she said.