Behind the closed doors of a classroom in Russia, an English teacher tries to weave in open and honest discussions about what’s happening in Ukraine into daily lessons.

She even dares to talk about the roots of fascism and the signs she says she sees of it in Russian society, but only when she trusts that her students won’t turn around and report her to their parents or the principal.

“If I feel uncertain about some of the students … I will never start such a talk,” she said to CBC News during a video call.

“But I do not want to be involved in these streams of lies.”

CBC News has agreed not to identify the teacher for her own safety because her classroom chats could be seen as criminal disobedience to the state, at a time when people have been fined or thrown in prison for much less.

Her attempt to have objective, free-flowing discussions comes as Russia ramps up the amount of state propaganda children are exposed to in schools. History textbooks have been rewritten to echo the Kremlin’s talking points when it comes to Ukraine, and its distrust of the West.

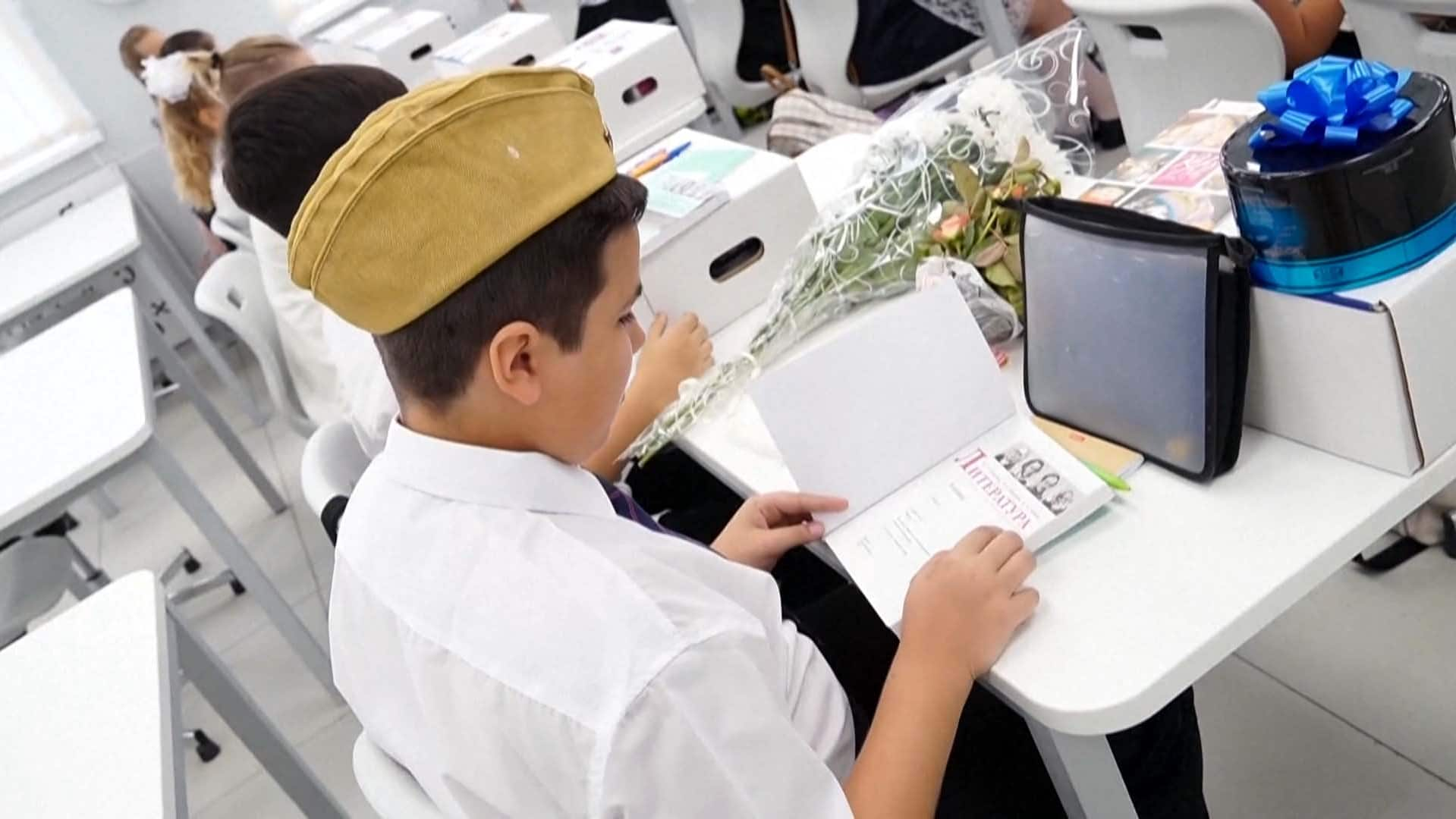

With examples of heroism of Russian soldiers in Ukraine and righteous justification for the invasion, the new Russian school curriculum brings Kremlin talking points to the classroom.

Curriculum changes

In classrooms, desks have been turned into shrines for the “heroes” killed in Ukraine, while students in Grade 10 and 11 will start receiving basic military training starting this month as part of the curriculum.

“When the war started, I could predict that they would introduce certain changes in the school program because they needed to brainwash the new generation,” said the teacher.

The changes made since Feb. 24, 2022, appear designed to breed support for the country’s war in Ukraine, and prepare students who may eventually have to fight in it.

For some teachers who are against the invasion, or even just the state-directed learning materials, there is little recourse, according to Daniil Ken, the head of Russia’s Alliance of Teachers, an independent union.

“They are really depressed,” he said in an interview with CBC News.

“It’s hard for them to leave because almost all education in Russia is under state monopoly.”

Ken, who used to teach and work as a school psychologist in St. Petersburg, fled the country after being arrested shortly after the start of Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine.

The Alliance of Teachers is a group that was set up and funded by Alexei Navalny’s anti-corruption foundation as a way to educate teachers about their legal rights.

Before the war, more than 90 per cent of the inquiries his group received were from teachers, he said, but now half of the messages they receive are from parents seeking contacts for private, out-of-school education for their children.

Ken acknowledges that his group isn’t representative of all of Russian society as the teachers he’s in contact with are against the war. It’s hard to ascertain how widespread that attitude is given that many fear speaking out, he added.

Arrests and fines

There have been a number of reports of teachers being fired or fined for criticizing the government and the war.

One father was sent to prison for two years for anti-war comments he made online.

They surfaced during an investigation that began after a teacher alerted authorities to a drawing his 12 year-old daughter made in school that depicted Russian missiles raining down on a Ukrainian mother and child, and the words “Glory to Ukraine” alongside it.

“The problem is that all the people who are against war are forced to be silent because the punishment is cruel,” said Ken.

He says the return of basic military training to high school, after it was removed from the curriculum during the 1990s, is significant.

A course guidebook viewed by CBC News says the training will help students understand military duty and service to “the Motherland.” It will also teach them first aid and how to protect themselves in dangerous situations.

Ken says the course is not just a copy of the soviet model of military training that was previously offered in schools because now there is “a real war and Putin needs the whole society” to support it.

Re-written textbooks

Last year, Russian schools rolled out a weekly lecture called “Conversations about Important Things,” and to kick off the school year, Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered a lesson to a handpicked group of students on Sept. 1.

He recounted a story about the Second World War before telling students “we were absolutely invincible, just as we are now.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke to a group of students on Sept. 1, known as Knowledge Day in the country, as part of an initiative aimed at boosting patriotic sentiment in schools.

Putin’s perspective on history, from the collapse of the Soviet Union to what Russia calls its special military operation in Ukraine, is laid bare in four texbooks that were recently written by a Kremlin aid.

CBC News received a PDF version of one of the textbooks, which chronicles Russian history from 1945 to present day. It describes Ukraine as an “ultra-nationalist state” where the opposition is banned and “everything Russian, declared hostile.”

The book says the West helped move anti-Russian politics into the Ukrainian government which destroyed the country’s economic and cultural ties with Russia. The text reads that the West’s ultimate goal is “the dismemberment of Russia and control over its resources.”

As for the launch of the “special military operation,” the book quotes Putin, who frequently says that Ukrainian nationalists started it. It adds that Russian soldiers who have “liberated” Ukrainian cities have found evidence of “abuse of civilians and torture.”

Not included in the book is the widespread concern expressed by several human rights groups, along with the UN, about Russia’s widespread the torture and abuses carried about by its military.

‘Poisonous’

Tamara Eidelman, a Russian historian who now lives abroad, read the nearly 500-page textbook and describes it as “poisonous.”

“It puts together all the terrible ideas that Russian propaganda has been using for the last several years,” she said.

Eidelman was previously head of the history department at a Moscow school, but left the country in 2022 after publicly criticizing the war. She is now delivering history lectures to audiences in Europe.

She says her old school is currently without a history teacher because one of her colleagues resigned and left the country a few months ago. The school has been unable to recruit another, she said.

She says the teachers she knows feel like they are in a terrible position, but so are some of her former students whom she communicates with through a Facebook group. They ask her advice about whether it’s worth it to study history at a university in Russia, and she says she’s at a loss on what to tell them.

“Either you fight and have big problems … or you sit in class and say nothing,” she said.