The decision to close all English school buildings built using potentially collapse-prone lightweight concrete just days before the start of the academic year has caused a political firestorm in the UK.

While fewer than 1 per cent of schools and colleges are affected, the possibility that other public buildings — including hospitals, courts and prisons — might contain the material has led the opposition Labour party to accuse the Tory government of presiding over a decade of austerity-driven neglect of UK public infrastructure.

The true extent of the problem caused by reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete, or Raac, in the public and private sector is still to be determined, and the Financial Times looks at the facts behind the furore.

What is Raac?

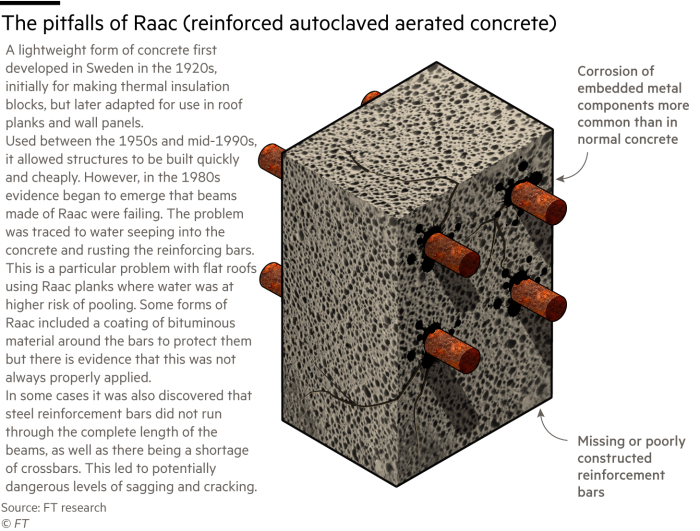

Reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete is a lightweight alternative to traditional reinforced concrete with good fire resistance and thermal insulation properties.

It was principally used between the 1960s and 1980s to make roof planks and walls. Its flaws — including a vulnerability to water seepage — have been known for decades. Roof collapses in the 1980s were followed by a UK government paper on its problems in 1996. In 1999 the Standing Committee on Structural Safety, an expert group, issued warnings about its use.

In 2018, the sudden collapse of a Raac roof in a school led the Department for Education to alert educational authorities to the material’s potential problems. In a subsequent bulletin, Scoss warned that “pre-1980 Raac planks are now past their expected service life and it is recommended that consideration is given to their replacement”.

Why are England’s schools so badly affected?

According to a National Audit Office report in June, the DfE had identified 572 schools with a potential Raac problem, a legacy of England’s particular education policy history.

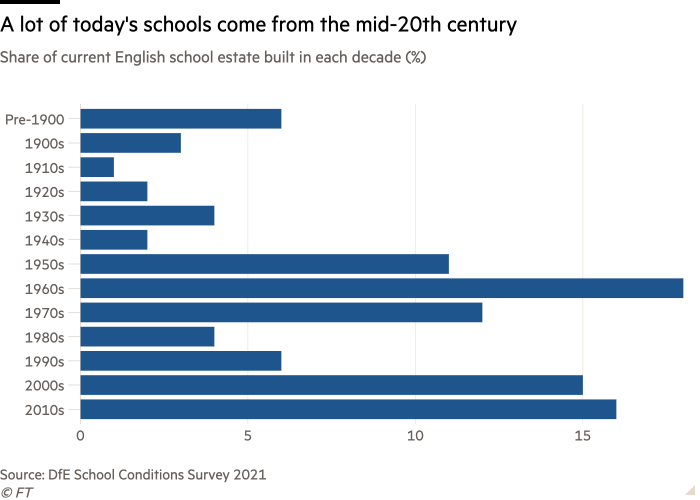

The English school estate expanded dramatically in the mid 20th-century, driven by the need to find places for children following the UK’s two post- war baby booms, which peaked in 1947 and 1964, and the raising of the school-leaving age to 15 in 1947 and 16 in 1972. About a third of current school floorspace was built between 1950 and 1979.

Whose fault is it?

The last Labour government’s Building Schools for the Future programme, which was announced in 2004, might have dealt with a large part of the problem: it was intended to rebuild or renovate the secondary school estate. However, it was cancelled by the Conservative-led coalition government in 2010.

Since then, the budget for rebuilding schools has been squeezed further. The Institute for Government think-tank estimates that the overall DfE capital budget fell by more than a third between 2007-08 and 2020-21, from £7.9bn to £5.1bn in real terms.

The demand for new places (including “free schools”, the government’s programme for opening new schools) has meant that money has been spent on expanding stock, leading to more than a decade of extreme underspend on maintenance.

How much will it cost to fix?

The DfE will need to bring forward plans to replace or repair buildings with Raac. Repair may not require rebuilding, however. Scoss noted that there are cases where “the planks have been replaced with alternative structural roofs or the spans have been shortened by the introduction of secondary supports”.

If the department replaced all ageing Raac buildings, the cost would likely rise into the billions. The DfE’s last estimates, published in 2022, implied that rebuilding a single average-sized 1950s block at each of the 572 schools would total about £3.1bn.

However, schools may have more than a single block in need of rebuilding and costs would rise further depending on the availability of temporary accommodation.

Can ministers put the crisis behind them?

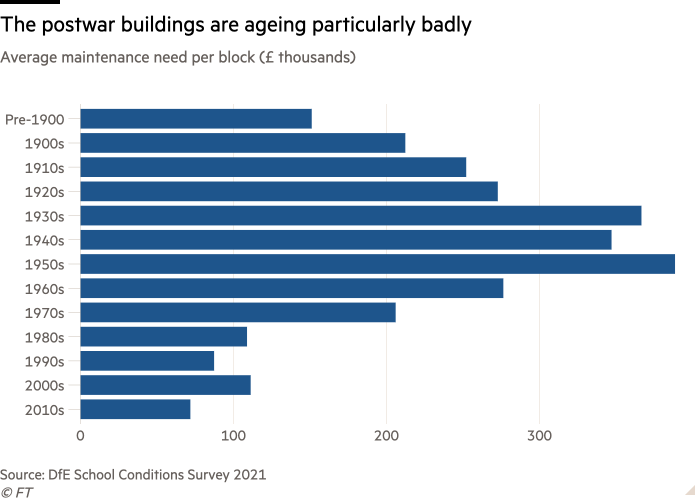

Maybe not. Raac is only one element of an even larger school repairs problem. The DfE’s own annual report warns of the “risk of collapse of one or more blocks in some schools which are at or approaching the end of their designed life expectancy and structural integrity is impaired”.

In 2021, the DfE estimated it needed about £6bn for repairs of buildings put up in the 1950s-1970s. These account for half of the school repair bill of £11.4bn. The average 1950s school building needs almost £400,000 of maintenance work.

Because of these ageing buildings, the school estate is in more need of work than the NHS, which has an estimated £10bn maintenance backlog.

Beyond the general condition of the estate, “system-built” schools — made from pre-assembled parts put together on-site — built between 1945-1970 are ageing badly and are a particular worry. The potential cost of replacing them dwarfs any potential Raac problems. The DfE has concerns about 3,800 blocks.

Do other sectors have a Raac problem?

Nobody is sure, which is part of the problem for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak as he seeks to change the political narrative around “crumbling Britain”.

According to the DfE, only 156 of the 14,900 schools that were sent questionnaires about Raac found the material; of these, only four were forced to close fully, with pupils switching to remote learning.

However, Whitehall insiders said the DfE’s initial decision to vacate all areas containing Raac, rather than follow existing guidance of structural engineers to first monitor and then prop up affected areas, had put pressure on other departments.

A cross-Whitehall exercise is under way to assess the extent of Raac in other buildings, including hospitals, courts and prisons. The responsible authorities have said that in most cases they have the space and flexibility to manage the problem.

NHS England said on Tuesday that Raac had been identified on 27 sites in 23 hospital trusts since 2019. It has since been eliminated in three. NHSE said more sites could be identified when additional assessments were completed this week.

The Ministry of Justice has found Raac in seven courts built between the 1960s and 1980s but the sites have since been deemed safe after being assessed and tested. Harrow Crown Court in outer London has been closed for at least six months after the substance was discovered there, but cases have been transferred to other courts.

Are other countries affected?

Patrick Hayes, technical director of the Institution of Structural Engineers, said the UK is ahead of other countries in identifying the problems with Raac because it has a system in place that allows confidential reporting of structural problems with buildings.

Hayes said that his teams are being contacted by engineers from across Europe who are seeking to better understand the problems identified in the UK.

British government officials say that after problems emerged in UK schools they were instructed to find out what other countries were doing. “We couldn’t find any other country with a comprehensive Raac action plan,” said one.

Reporting by Peter Foster, Anna Gross, Jane Croft, Sarah Neville, Chris Cook and George Parker