The Current23:26Storm Fiona’s lingering impact in Newfoundland

It’s been a year since Peggy Savery’s home was ripped into the sea by post-tropical storm Fiona, but she’s still finding her old belongings washed up on the Newfoundland shore.

“I just found these; that was a Christmas plate I had … this one had a candle on it,” said the Channel-Port aux Basques resident.

She’s also found old coins and cutlery, and shards of her mother’s fine china. There are toys that once distracted her cats, and even a part of her old microwave.

“That’s the hard part, I think, is finding all those things and knowing it’s still sitting around,” she told The Current’s Matt Galloway.

“[I’m] just maybe hopeful that maybe one time I might find something of sentimental value that’s still hanging on.”

Fiona made landfall on Sept. 24 last year, creating an enormous storm surge that destroyed 100 homes and killed one woman in Channel-Port aux Basques. Jutting out into the ocean on the tip of southwestern Newfoundland, the fishing community is home to around 4,000 people. Almost a year later, some residents are grappling with whether to rebuild or move away — a question tied to whether they can ever feel safe again so close to the ocean.

The now-iconic picture of Josh Savery’s family home in Port aux Basque, N.L., teetering on the edge of a cliff captured the terror of post-tropical storm Fiona in a single image. While the famous picture reminds the family of what they lost, it also attracted an outpouring of sympathy and kindness.

As the storm receded last year, news reports around the world carried a picture of Peggy’s house, already battered by the storm and slouching toward the churning ocean below. Moments after that photo was taken, a wave came over the top of the house and pulled it from the rocks it was built on.

It’s not how Peggy likes to remember what she calls her “dream home,” with ocean views and a deck that stretched out over the water. She prefers to think of evenings on that deck with her husband Lloyd, stargazing and listening to the dark water lapping the shore below.

She visits the site a few times a week to see what the ocean has spat back, and try to wrap her mind around everything they’ve lost.

The couple and their son, Josh, have since moved into a new house, albeit one that doesn’t quite feel like home yet. Their new place is further inland, away from the ocean that “used to lull me to sleep at night,” she said.

“Now I just look at it differently … I can’t imagine sleeping here at night, sleeping this close to it. That’d be a little scary.”

‘Panic in his voice’

Peggy and Lloyd had intended to stay home and wait out the storm last year — until Lloyd went outside briefly to get timber, and noticed the roiling sea was higher than he’d ever seen it.

He rushed back inside to tell Peggy they had to leave.

“There was a bit of panic in his voice, but I still didn’t take it serious and I said, ‘Well, I’m going for a shower first,'” Peggy said.

“And he just said, ‘You don’t have time. We have to go.'”

Peggy grabbed their cats, but Lloyd didn’t stop to take even his wallet or his glasses. They went to his brother Ben’s house, where the two men decided to check in on Ben’s son Scott Savory, who lives right across the cove from his Aunt Peggy and Uncle Lloyd.

Footage shot over Port aux Basques, N.L., shows the damage caused by post-tropical storm Fiona.

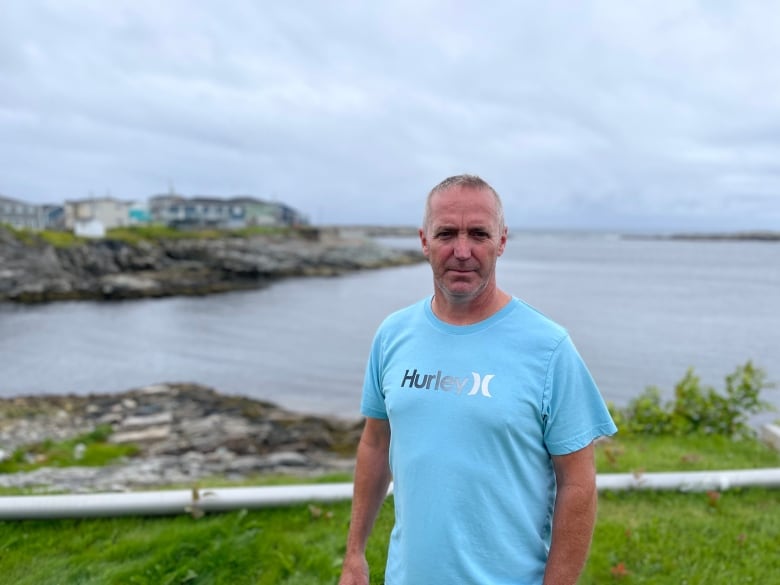

Scott’s house is about 10 metres above sea level and 30 metres from the shoreline, but waves were already hitting it. The younger man was trying to get his motorcycle out of his garage, and enlisted his father’s help.

“We weren’t here for 10 seconds, and another wave hit and caved my garage door in and pretty much pinned myself and my dad back in a corner,” said Scott.

The water was waist high but they managed to push off the debris and make for the exit.

“We got out front and we noticed that Uncle Lloyd was standing just on top of the hill there watching towards his house — and his house was getting demolished.”

Demolition adds to heartbreak

Fiona washed away Scott’s backyard, as well as much of his work equipment. There’s a watermark half a metre up his walls, yet the house itself is still standing.

But his home is one of 60 buildings that have been marked for demolition, in an impact zone close to the ocean. The provincial government has ruled it’s just not safe for anyone to live there.

Scott has to be out by spring.

“It’s going to be heartbreaking to give up what I worked so hard for over the last ten, 12 years,” he said.

He intends to stay in the community, but he too struggles with being close to the ocean. He watches weather reports for storm warnings, and feels Fiona took away his “peace of mind.”

He said the bigger loss is not having his aunt and uncle just across the way. Before the storm, he would often pop in after work to sit on their deck and enjoy a beer together.

Not being able to “look over and yell at Lloyd and Peg … it just changed everything,” he said.

The emotional fallout and “intangible costs of climate change are things that we often forget about,” said Kelly Vodden, a professor in the environmental policy institute at Grenfell Campus at Memorial University.

“To have to move away from the coast where they have their identity and connections and histories, certainly there’s an incredible cost there,” she said.

Andrew Parsons, Channel-Port aux Basques’s representative in provincial parliament, said ongoing mental health support is available to people whose homes are due for demolition — as well as the wider community.

“The impact wasn’t just those who lost homes … it’s really been a cumulative effect on the entire community. But supports have been provided,” said Parsons, who is member of the house of assembly for Burgeo-La Poile and also the province’s minister of industry, energy and technology.

To stay or go

Peggy’s other nephew, Shawn Savery, also suffered extensive damage to his home in Channel-Port aux Basques — but his house isn’t in the demolition zone, which means no buy-out.

“The foundation has cracked, the siding has cracked. My sewer system was demolished, my basement was flooded out with probably three feet of water,” he said.

Shawn said his family was thinking about moving before the storm hit, but he doubts he’d find a buyer now and isn’t even sure he’d be comfortable selling.

“I wouldn’t be able to sell to anybody knowing that they could themselves be put in danger,” he said. That leaves him in “a tough place,” he added, made worse by the fear that another storm could hit.

In June, the provincial government said in a statement that it had outlined an impact zone in collaboration with town officials, “based on objective, evidence-based considerations including the debris line of the storm surge, aerial photography and on-site verification.” Property owners had been notified, and were receiving support from the provincial government, the statement said.

Parsons said the work of deciding the impact zone’s borders was “very much done with empathy in mind,” and added that he feels for people who might want to be included — but aren’t.

But he said there is no solution that would have been satisfactory for everyone.

Parsons, who is from Channel-Port aux Basque, said it’s been personally hard to watch the changes to the community, especially “where you’ve got an entire neighbourhood that’s almost no longer in existence.”

But he’s confident that the fabric of Channel-Port aux Basques can survive, even through the difficulties.

“Right now I still think that it is an everyday issue in the community for a number of people,” he told The Current.

“My hope is that it gets to the point where it becomes a memory, and not something that we are still living. But that takes time.”

The next storm

Vodden said that extreme weather events are going to “become more severe and more frequent” due to climate change, and communities like Channel-Port aux Basques need help to be ready.

“We need to put more resources and effort into helping communities understand what their climate change vulnerabilities are, and what some of the [adaptation] options are,” she said.

She said different areas will have different needs, so planning discussions must have local input — particularly with remote communities that find it hard to “get the ear of decision-makers.”

She said the risk of a failed strategy is division within a community, or even outright conflict where a government tries to move residents from homes they don’t want to give up. But she added that the destruction of Fiona has helped many people face up to what’s a “tough conversation.”

“Maybe some of the education also has to be in areas outside of these rural and remote communities about … how they need support in order to adjust,” she said.

Peggy said the storm has been a wake up call for her around climate change — but the wider world needs to pay attention too.

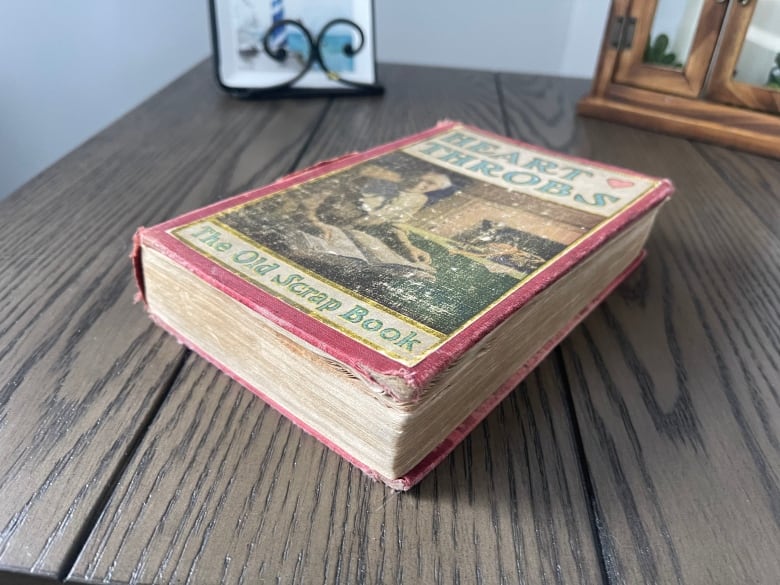

Back at her new house, a big storage box holds some of the sentimental-but-broken things she finds on the shoreline. But other items are on display, including a candlestick that her father bought her when she was 17.

“Lloyd’s nephew went diving one day to see how bad it was down there. He brought this up and had no clue that it was mine or what it meant,” she said.

Sometimes “you win the lottery,” she said.