Receive free UK local government finance updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest UK local government finance news every morning.

This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Birmingham city council has become the latest and largest British local authority to declare bankruptcy, while the Raac affair (“Schoolgate” is my favourite of your suggestions for what to call the issue so far) continues to cause anxiety for parents and political pain for the government. The two stories are linked in that they both, inevitably, mean further increases in public spending.

Inside Politics is edited by Georgina Quach. Follow Stephen on X @stephenkb and please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to [email protected]

Cut and bust

What are the two easiest ways to cut public spending? The first is reducing infrastructure spending because, while everyone notices right away if you shut their school, hospital or police station, usually it is someone else’s problem if in 10 years’ time a school, a hospital or a police station collapses.

This is why Alistair Darling after the financial crisis and Jeremy Hunt after Liz Truss’s mini-budget used reductions in infrastructure spending to deliver the bulk of their promised cuts, and why NHS England has raided its capital budget to pay for day-to-day spending.

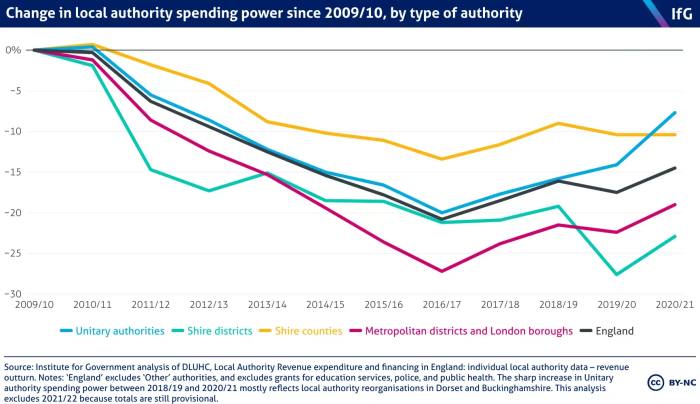

The second is by cutting the size of government grants, one of the core sources of revenue for local authorities.

These cuts have come as secular trends — the rise in ageing populations that Emma Agyemang and Chris Giles write about here, for example — have increased local authorities’ statutory costs and obligations. As Helen Thomas puts it in an excellent column on the topic today:

As central government funding has dropped, some councils sought more commercial opportunities or took more risk, increasing the complexity of their accounts. To preserve front-line services, finance departments may also have suffered cuts, slowing account preparation.

This is putting pressure on local authorities and inevitably leads to further local authority bankruptcies.

The big picture story of the government’s difficulties over buildings constructed with reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac) is that cuts to infrastructure spending now have political consequences. Have we reached that position with local government funding? Well, maybe.

Although a number of local authorities have gone bankrupt, they have all been either spectacularly unlucky, badly managed, or both. Birmingham city council is no exception. The present-day Labour-run local authority had, until relatively recently, been held up by Conservative and Labour politicians as a model authority: between the Labour-run council and the Conservative mayor of the West Midlands Andy Street, the two were seen as the best example of how to turn around a city centre and attract inward investment.

But in this case, the council’s spectacular bad luck is that previous (largely Labour) local councils were not well run. The failure to pay male and female employees equally has left the current council with a £760mn bill to settle historic compensation claims, on top of the £1.1bn that the council had already paid out as a result of a Supreme Court ruling in 2012 in favour of female former council employees.

Of course, failing to pay your employees similar salaries for similar work is not something driven by cuts to local government grants — in that respect, Birmingham city council’s problems are wholly unlike any other local authorities.

Regardless of the colour of the council — and all of England’s major parties run councils that have had to declare bankruptcy — what we have not yet seen is a council with relatively good governance and fortunes declaring that it cannot operate.

That is only a matter of time in my view: and the big political question is whether that happens during the last years of this government, or in the first few years of the next.

The Raac crisis has left both parties with tough questions to answer. The Conservative party, of course, has the difficulty of having been in power and overseen every spending decision for the past 13 years. Meanwhile its leader chose to spend less money on school maintenance than the Department of Education asked for.

But it has left Labour having to evade questions about what it would do, because every question about public spending runs the risk of forcing it on to questions about tax rises.

A similar dynamic means it is in both parties’ interests to depict the difficulties facing local authorities as, just that, local. An investment strategy gone wrong in Woking, a historic pay dispute in Birmingham — these things happen and in the grand scheme of things individual bankruptcies by local governments don’t add much to central government spending.

But the reality is they are part of a bigger trend. For all Hunt likes to pretend he will cut taxes and Rachel Reeves says that she won’t introduce new asset taxes, the “new age of big government” means that both politicians will be tax-raising chancellors.

Now try this

I saw The Innocent at the cinemas: a perfectly judged heist-comedy that manages to pack an awful lot of depth, complexity and humour into just 100 minutes. Nicolas Rapold’s interview with Louis Garrel, the director and star of the film, is very much worth your time, but it’s best enjoyed after you’ve seen The Innocent.

Every Friday a different woman from the FT selects her standout pieces of journalism from this paper and elsewhere in our newsletter Long Story Short. This week it’s the turn of FT editor Roula Khalaf. FT subscribers can sign up here to receive it exclusively by email on Friday.

Top stories today

-

No let up | Working-age UK households will see no improvement in living standards before the next general election expected in 2024, according to analysis published by a leading think-tank.

-

Aid source at risk | The source of billions of pounds of funding used by the UK Home Office to support asylum seekers could be “closed off” if new legislation aimed at curbing cross-Channel migration takes full effect, according to Britain’s aid watchdog.

-

Yousaf injects £1bn into welfare | Scotland’s first minister has sought to revive the fortunes of his crisis-hit, ruling Scottish National party with a legislative programme focused on a £1bn increase in welfare spending. Yousaf did not say how Scotland would finance its extra spending, given a weak economy and net deficit of 9 per cent of GDP in 2022-23.

-

‘Things felt different’ | Keir Starmer told his new shadow cabinet yesterday the party had to prove it was ready for power in the UK, as he put his top team on an election footing. Although Starmer warned colleagues against complacency — noting “not a single vote has been cast” — shadow ministers said there was a sense of a party mentally shifting from opposition to the prospect of power.

-

Hospitals check for Raac | NHS bosses have ordered all English hospitals to verify that any dangerous concrete on their sites has been identified and that evacuation plans are in place in the latest development in the UK government’s crumbling concrete crisis.

Recommended newsletters for you

One Must-Read — Remarkable journalism you won’t want to miss. Sign up here

Britain after Brexit — Keep up to date with the latest developments as the UK economy adjusts to life outside the EU. Sign up here