Like a visit to a Russian banya, going out for lunch in Dubai in midsummer requires traversing a whole gamut of temperatures. I stumble through the 43C heat, then plunge into the air-conditioned confines of 11 Woodfire, wiping the condensation from my glasses as I seek out the sanctioned oligarch Andrey Melnichenko.

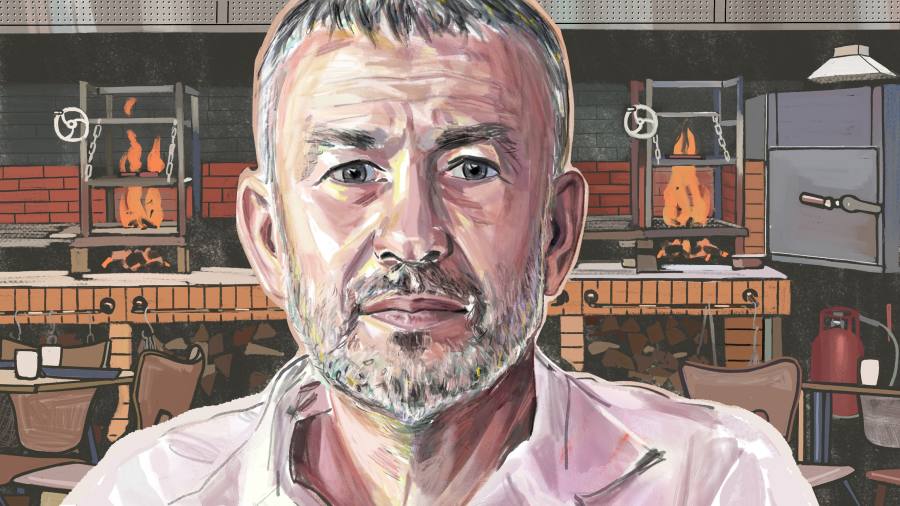

The Michelin-starred restaurant in the upscale suburb of Jumeirah is a rare excursion for Russia’s richest man. Seated at a corner table, Melnichenko is dressed for the weather, inasmuch as that’s possible. “I don’t know the city too well and I don’t get out to lunch much,” he tells me as he studies the menu.

Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year made Melnichenko, as he puts it, a “pariah”, ending the cosy life he enjoyed in the west through the proceeds of his booming coal and fertiliser empire.

The EU sanctioned Melnichenko in March 2022 for attending an oligarchs’ roundtable with Putin in the Kremlin a few weeks earlier on February 24, the first day of the war. This prompted him to leave his villa in St Moritz for the United Arab Emirates, where he had become a citizen in 2021, and to remove himself as a beneficiary of the trust that owns his empire. His $300mn Motor Yacht A has a berth here, a safe haven compared to that of its bigger brother, the $600mn Sailing Yacht A, which was seized by Italian authorities in Trieste.

A wartime rise in fertiliser prices has, however, doubled Melnichenko’s fortune to more than $25bn, according to Russia’s edition of Forbes. And for Moscow’s elite, the UAE is the place to spend it. Sanctioned in the west, rich Russians such as Melnichenko have found themselves at home amid Dubai’s bling-and-yachts aesthetic.

11 Woodfire has just opened and, like much of Dubai this time of year, its industrial-chic interior is largely devoid of customers. The searing heat has left Melnichenko, tall and trim at 51, without much of an appetite. He orders a beetroot starter with feta and woodland berries, followed by a side dish of grilled eggplant. I opt for a sea bass carpaccio and grilled leeks, wistfully glancing at the fresh fish, lamb chops and steak main courses on the menu as I do so.

Melnichenko pre-empts my thoughts of wine. “I don’t touch alcohol when I’m here, as an Emirati. I try to follow the local customs,” he offers by way of explanation.

Melnichenko admits that the war caught him by surprise. He had flown to Moscow for what he expected would be a routine Kremlin visit for the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, an oligarch lobbying group. “You have to meet officials pretty often. How else are you supposed to work in the country?” he says. “You wake up and see missiles flying on TV, and you have a choice to go or not. How can you not go?”

Russia’s business elite sat ashen-faced as Putin told them he had been forced to start the war and demanded that they rally around the Kremlin. Many of the attendees lamented that the empires they had spent decades building were ruined, and sank into despair.

But Melnichenko, as I will learn over our four-hour lunch, is not the despairing type. He repeatedly mentions a recent speech by CIA director William Burns, who said the world is going through a “plastic moment” of the sort unseen since the end of the cold war. “So much is changing,” Melnichenko remarks.

It’s an environment in which Melnichenko knows how to thrive. Born to a Belarusian father and Ukrainian mother in Soviet Belarus, he got his start in business while studying theoretical physics and field relativity at Moscow State University in the late 1980s, just as the USSR began to allow private enterprise. At 19, he set up a currency exchange booth with two friends that gradually evolved into MDM, one of Russia’s biggest banks.

The Kremlin’s strained public finances meant that Russia’s bankers called most of the shots, allowing the original oligarchs to buy the crown jewels of Soviet industry for a song in the infamous 1995 loans-for-shares scheme. The deal helped stave off a communist revanche, but proved a “catastrophe” for the oligarchs in the long term, Melnichenko says. “This created a hatred among the Russian people [for the oligarchs] that set off shockwaves that eventually brought Putin to power.”

Melnichenko wasn’t involved in loans-for-shares, but he spotted an opportunity a few years later to snap up distressed assets in the less glamorous fields of coal, metal pipemaking and fertilisers. By that point, Putin had clipped the oligarchs’ wings. “You either do business or politics. It’s clear and simple. I wasn’t interested in politics so a deal like that suited me just fine,” Melnichenko says.

Under the new rules of the game, Melnichenko built EuroChem into one of the world’s largest fertiliser producers and Suek into Russia’s biggest coal company. As his businesses boomed, he married Serbian singer and model Aleksandra Nikolić and moved to Europe, spending just five weeks a year in Russia.

The shock of the war wasn’t enough to jolt Melnichenko into realising that his old life was over. He went home to Switzerland, then headed off to celebrate his birthday near Mount Kilimanjaro, only to discover that the EU had sanctioned him a day later.

“I honestly wasn’t expecting it,” he said. “I’ve been living in Switzerland for 14 years. I don’t make weapons for the war. I make food for people and energy for power stations all over the world. I don’t promote the war. I’m not involved in politics. What’s the point?”

We move to another table to escape a loud couple next to us in the otherwise mostly empty restaurant; Ice Cube’s “It Was A Good Day” plays languidly in the background. Melnichenko has made quick work of his beetroot. My thin cuts of sea bass have been expertly seasoned with lime and chilli. We are already on a second bottle of water.

11 Woodfire

Villa 11 75B Street, Jumeirah 1, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Bottle of San Pellegrino x3 102 AED

Beetroot with feta and berries 50 AED

Sea bass carpaccio 65 AED

Eggplant 55 AED

Leeks 45 AED

Sencha tea x2 42 AED

Total (incl tip) 400 AED

In sanctioning the oligarchs en masse, the west hoped they would rise up to protect their riches and stage a palace coup against Putin, or at least call for an end to the war. I ask Melnichenko why that didn’t happen — are Putin and his security services too entrenched, and the oligarchs too weak? But Melnichenko doesn’t appear to think Putin is primarily responsible for the war at all.

“This was a global mistake. The people who tried to stop it didn’t do their job,” he says. In Melnichenko’s analysis, the west let things spiral out of control when it decided Russia was a “rusty petrol station” in terminal decline due to its over-dependence on oil and gas. “What does a weakening power do? You can’t solve domestic problems? Then you go to war.”

Putin has said many times that he had no choice other than to start the war — but, I point out, has always framed it as his decision.

But “life is much more complicated”, Melnichenko says. Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy is responsible for the war because “he made it a goal of his election campaign to avoid the war, but provoked his strong, aggressive neighbour into doing it through his extreme unprofessionalism”. The CIA’s Burns failed when the US declassified intelligence that Putin was planning the invasion. “That means he did his job badly and couldn’t achieve what he needed to — to avoid the war.”

Melnichenko says “the responsibility is collective” — so I ask him if he feels any guilt for the war. “I absolutely don’t consider myself personally responsible for the tragedies that have happened,” he says, insisting that the fault lies with world leaders. “Trying to work out who is guilty and not guilty is very dangerous.”

Our sides have passed with barely a thought. Melnichenko orders us a pot of green tea. The oppressive Dubai air conditioning has spurred me on to a third bottle of water.

Worried that we are talking at cross-purposes, I ask Melnichenko if he resents the west for sanctioning him — and, a few months later, his wife, after she became the beneficiary of the trust that owns his assets. He shrugs it off. “It’s like any natural disaster, a rain, a hurricane. What can you do? It is what it is.”

The only Russian billionaire to criticise Putin over the war is eccentric fintech tycoon Oleg Tinkov, who has claimed the Kremlin forced him into a “fire sale” of his bank over his anti-war comments. Equivocal statements from the likes of Melnichenko — who last March said: “The events in Ukraine are truly tragic. We urgently need peace” — frustrate Tinkov, who said the oligarchs had become hostage to their own fortunes.

“What do you need ebitda [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation] for if [Ukrainian] women and children are being killed? . . . But they all love money so much, they think they’ll live forever and die with their billions,” Tinkov told independent Russian news site The Bell. Melnichenko “hates Putin”, but had been forced to accept the war by the west, Tinkov added. “He’s under all the sanctions in the world, so he can only go to Dubai and sit in 60-degree heat.”

The comments are clearly still a sore point. “He’s lying. He’s trying to talk about his own high moral qualities,” Melnichenko ironises, refusing to be drawn further.

Melnichenko is far more animated about the broader consequences of the sanctions against him, which have become part of a global tug of war over grain exports from Ukraine’s Black Sea ports. Melnichenko likens these sanctions, which he says have driven up global food prices and precipitated a hunger crisis in poor countries, to the US nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. “It didn’t hit many military targets, the war’s outcome had already been determined, and the suffering [is] enormous,” he says. “It’s exactly the same.”

Melnichenko then spends considerable effort trying to get me to agree with him on this, waving away my protests that he’s wrong to decry the sanctions in such terms while remaining so equivocal about their root cause — the war that Russia started. “If you are harming millions who have nothing to do with the conflict, you are a war criminal,” he says, making the case that sanctions are economic weapons of mass destruction. “Don’t hide behind the term collateral damage — it’s a crime. It doesn’t matter why you did it.”

I ask Melnichenko if what Russia is doing in Ukraine is a crime. “In my view, yes,” he says. He subsequently got in touch with the FT to say his answer referred to specific scenes of attacks on civilian targets which are, in his view, a crime.

“In my view, many events . . . once again, I’m not on the ground, I’m not on the ground, I am not an expert, I cannot describe this or that specific instance.”

But he’s seen the same pictures of destroyed cities as I have, I say. “Once again, I wasn’t on the ground, what can I say? We are getting distracted here. War brings up all sorts of odious people to the surface from both sides. There are definitely war crimes from both sides. This happens in any war. It’s natural. It doesn’t matter who started it.”

Having failed to convince him that it does matter, I ask Melnichenko what he thinks about the warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin, whose Wagner paramilitaries staged a failed mutiny two weeks before our meeting. (A few weeks afterwards, Prigozhin would die in murky circumstances in a plane crash.)

Melnichenko says the stability of Putin’s regime depends less on internal conflicts than his ability to win the war. “How’s the leader of my country going to look in five years? Someone who defended the country from a parasite that grew and could have grown bigger, but he stopped it from crossing the line? Or a loser who became isolated and started making maniacal decisions? The winner will decide,” he says. In that time, “the chaos will intensify . . . it looks like gladiators fighting in the Coliseum.”

Melnichenko worries that the long-term consequences of the war will be felt well beyond Ukraine. “I don’t see a trend for de-escalation anywhere, unfortunately. That scares me,” he says. “The longer things go on and the more [society’s] expectations are thwarted, the harder it is to mobilise it. There’s a limit to how long propaganda can rally people for destruction. People get tired of it and want to move on. Leaders start losing popularity.”

In Moscow elite circles, the mutiny has fuelled worries of a “time of troubles” verging on civil war. “[But] the time of troubles won’t be limited to Russia,” Melnichenko says.

“In cultural studies there’s a concept of the time of carnivals, and the time of orgies. Carnivals are when everyone puts on a mask and plays by the rules. Orgies are when everyone goes crazy. We’re in the time of orgies. And it very much looks like it’s not going to end well.”

Surely, I say again, the ultimate responsibility for that lies with Putin — but this is not how Melnichenko sees the world. “It’s pointless to talk about good and evil, because it all depends where you’re looking at it from,” he says. “This is a time when the masks are off, and everyone is going wild.”

In the weeks following our interview, Melnichenko runs into trouble in Russia, where the state has moved to nationalise a set of thermal power plants he owns in Siberia. The case is part of a wave of wartime seizures as the Kremlin seeks to reward cronies with prime assets. Their owners may have fallen out of favour — or simply been caught owning a profitable company at the wrong time.

I’m reminded of what Tinkov — who has since had UK sanctions against him lifted partly thanks to his uncompromising anti-war stance — said about Melnichenko: “You can’t sit on two chairs at once,” or you risk falling out with both Russia and the west.

But then I recall Melnichenko’s final thoughts about sanctions. “Their only goal is to influence people and create chaos. Because when you make someone a pariah, you create chaos in the system,” he says.

“If you’re looking for a judgment of one side or the other in what I say, you’re wrong. There isn’t one. Everyone who let things get to this is guilty,” Melnichenko says. “Journalists and other propagandists are guilty for creating narratives that divide people instead of bringing them together. Everyone who is looking for the reasons for it while people are dying. We have to find a solution. And you can’t find them in the short term,” he says.

Max Seddon is the FT’s Moscow bureau chief

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on X