Receive free Travel updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Travel news every morning.

Porte des Lilas — “Gate of Lilacs” — is a place name lovely enough for Clive James to have used it as the title of his long poem about Marcel Proust. It once denoted a gate in the Thiers Wall that surrounded Paris. Today, it’s applied to a bland, grey suburb of north-east Paris and a Métro station serving quiet line 11 and even quieter 3 bis.

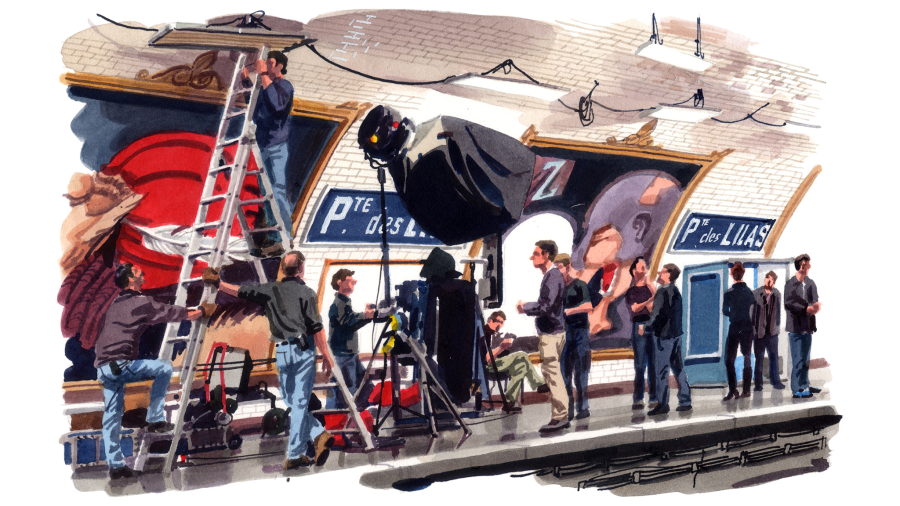

The station, in Art Deco style, is modestly attractive, with its scalloped roof reminiscent of a seaside pavilion. But its main distinction is that it harbours two secret platforms closed to the public and glamorously repurposed as a film set.

As a press guest, I will be visiting the Porte des Lilas cinema platforms with a team of Métro technicians who are testing some photographic technology beyond my comprehension. I meet them in the bistro across the road from the station, where they’re having a quick French lunch break (just the three courses).

The head of the party breaks off from crème brûlée to explain the origins of the cinema platforms. Drawing on the back of a menu, he explains how, in 1921, when Porte des Lilas station was opened, a shuttle service originally connected it with Pré-Saint-Gervais station on nearby line 7. The shuttle, never busy, was killed off in 1939, and the platforms serving the connection were closed to the public, becoming collectively known as quai mort, until the 1970s when their cinematic afterlife began.

After coffee, we cross the road and enter the station; down an escalator with two or three voyageurs ordinaires as the head of our party calls the regular punters; then, after some twists and turns through progressively quieter corridors, we stop at a door that I would not have noticed at all had I been on my own. The head of our party unlocks it, and we are into a corridor that is definitely not ordinaire because all the poster frames are filled with blank green paper. We descend some dusty steps and here are the cinema platforms, a sight at once ghostly and yet familiar in its standard Métro elegance.

There is the typical white vault, attractively reminiscent of the wine cellar of a château, and the lights are on, giving that melancholic Métro glitter — a moonlight-on-sea effect, caused by electric light on bevelled tiles. But the empty platforms are a blank canvas. The ceramic poster frames, much larger than the corridor ones, contain the same green paper. Today, the station name does read “PTE. DES LILAS”, but it’s often called something else and, as the technicians go about their incomprehensible work, I reflect on the filmic manifestations of Porte des Lilas.

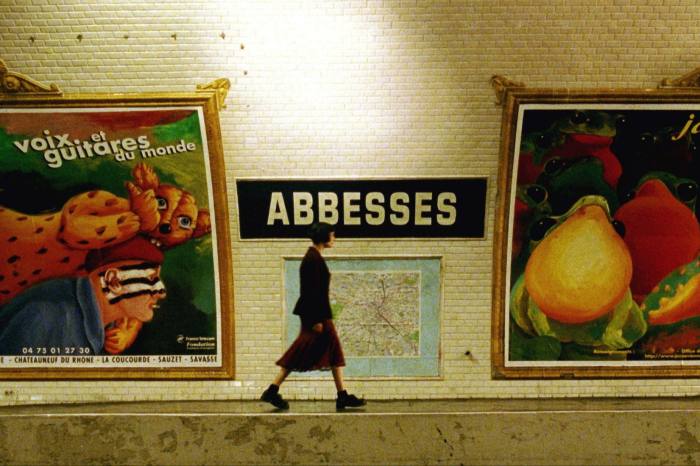

In Amélie (2001), it stands in for Abbesses station in picturesque Montmartre, where the ingénue heroine supposedly lives. The poster frames contain adverts for orange and green products, the film being steeped in those hues. In “Tuileries”, on the other hand, a violent little tale by the Coen brothers — a component of the portmanteau film, Paris Je t’Aime (2006) — Lilas stands in for Tuileries station. (Steve Buscemi plays a tourist who becomes embroiled with a Parisian couple rowing on the opposite platform.)

Porte des Lilas is called “Porte des Lilas” in Julie & Julia (2009), in which it represents the home station of the gauche American cookery writer Julia Child, played by Meryl Streep. Child did live in Paris in the 1950s, but on rue de l’Université in the 7th arrondissement, nowhere near Porte des Lilas.

In John Wick 4 (2023), Lilas keeps its real name, and plays the role of the ghost station it would have been had it not become a film set — so the poster frames contain the tattered remnants of posters, such as can be seen in genuine stations fantômes, like Saint-Martin on lines 8 and 9, which is visible, just about, from passing trains.

The cinema platforms retain the features appearing on most Métro stations until the 1970s. These include the long, slatted wooden benches, phased out because tramps slept on them. There are also two of the old station masters’ kiosks, resembling greenhouses sawn in half and attached to platform walls. One of the two at Lilas was given some 1940s trappings in Female Agents (2008), in which the station masquerades as Concorde, and the two principal women in the scene — intent on assassinating a Nazi officer — do enter the Métro at the real Concorde.

Also forlornly surviving at Lilas are the collapsible stools on which the poinçonneurs or poinçonneuses sat punching tickets and sometimes, in the latter case, knitting. In 1959, a short black-and-white film (it’s on YouTube) was made to accompany Serge Gainsbourg’s song, “Le Poinçonneur des Lilas”. Shots of Gainsbourg glumly punching tickets are interspersed with spectral Métro scenes, some apparently filmed at Porte des Lilas in the days before the cinema platforms were open for business. Both song and film seem to mark an early recognition of the latent glamour of this low-key, poetically named spot.

Andrew Martin’s book ‘Metropolitain: an Ode to the Paris Métro’ is published by Corsair on August 10

DETAILS

The Porte des Lilas cinema platforms will be viewable as a part of a guided Métro tour during the annual Paris Journées du Patrimoine. Details will appear at ratp.fr later this month. Rapid booking is advised.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter