Good morning. A bit of a rough day for the US yesterday: our former president was indicted and Fitch downgraded our debt, citing “a steady deterioration in standards of governance over the last 20 years”. We’re not sure, as of now, how significant either event is, but we welcome your thoughts: [email protected] and [email protected].

Earnings season (and the soft landing)

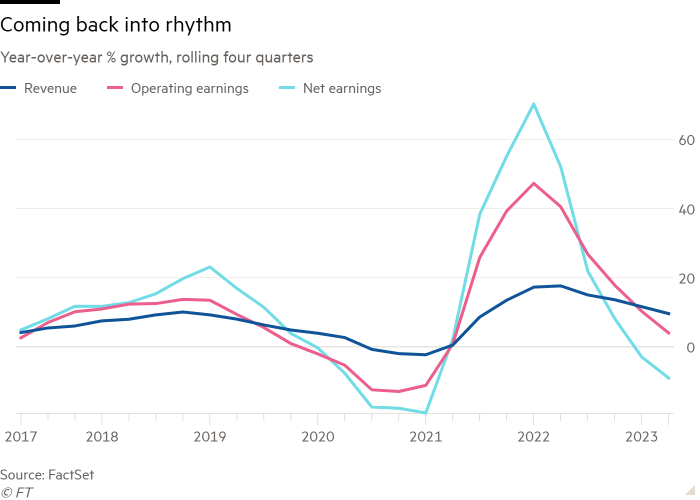

Halfway through the earnings season, the headline numbers may look a little soft — but the underlying details reflect a resilient economy that is supporting solid corporate performance. For most companies, things are not quite as good as they were a year ago, but they are still pretty good.

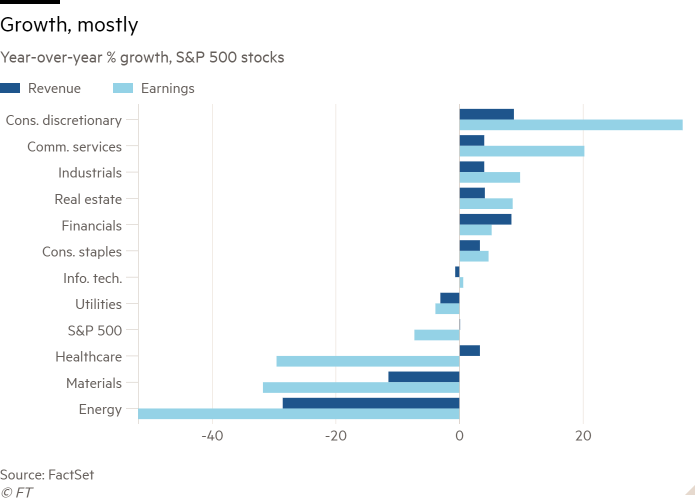

According to FactSet — which blends actual results with analyst estimates for companies that have not reported — S&P 500 earnings in the second quarter are set to fall 7.3 per cent year over year. That’s the biggest decline since the first, ugly quarter of the coronavirus pandemic. But, crucially, the declines are concentrated in just a few sectors: energy, materials, utilities and healthcare. The first three of those are reflective of a hard turn in the commodities cycle, while the last is hit with high costs and some firm-level idiosyncrasies:

Despite falling headline earnings growth and flat sales, it is hard to see a cyclical slowdown taking hold when sectors such as industrials and financials are still showing solid growth (a favourite Unhedged cyclical bellwether, Caterpillar, reported 22 per cent revenue growth yesterday, with 32 per cent growth in North America). What we are seeing, instead, are corporate results consistent with normalisation following the exceptional pandemic period:

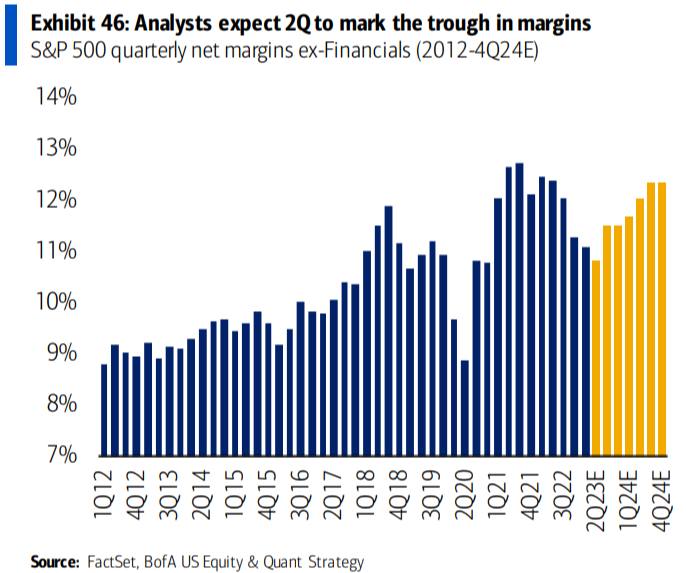

Margins continue to compress. Net profit margin is expected to come in at 11.3 per cent for the quarter, according to FactSet, a full percentage point lower than last year. But this is what one would expect as inflation cools and demand comes back into balance.

What is alarming on the margins front, if anything, is investors’ expectation that this quarter will represent the low point, and a sharp rebound is coming. Ohsung Kwon and his team at Bank of America point out that the pace of margin decline has slowed. Still, Unhedged can’t see why margins would return to the dizzy pandemic highs — which, as this chart from BofA shows, is exactly what consensus expects:

The best reason for long-term optimism on margins is that companies are investing. Companies that have reported thus far have grown capital expenditures at a 15 per cent rate, Kwon points out. This is very welcome after years of under-investment, but the payback periods on fixed investment are longer than a year or two. In the short term, it can crimp margins by raising depreciation expenses.

The news from second-quarter earnings, in sum, is absolutely consistent with the “soft landing” forecast that becomes more popular by the day on Wall Street. But while Unhedged lowered its recession odds a few weeks ago, we still think the chances are significant (more than one in three). At the risk of becoming repetitive, we have two simple reasons for staying off the bandwagon: the tight labour market, and the fact that monetary policy operates with lags.

On the first point, Don Rissmiller of Strategas provides a sober and succinct summary:

We are running the US economy at a pace that requires 171 million workers, when we only have 167 million available in the labour force. If labour supply is basically stuck (eg, ageing demographics), then that implies labour demand should come down. The “softest” way for that change to happen would be for job openings to decline instead of jobs — but the risk remains that we get some of both . . . The key issue is that as long as there’s an imbalance (labour demand > supply) the central bank is likely agitated & set to continue restrictive policy . . . A few improved inflation readings likely aren’t enough

On the second point, David Rosenberg, the well-known strategist, makes the point late in an economic cycle, before recession sets in, soft landing talk is always popular:

As everyone gushes over the +2.4% annualized real GDP growth spurt in Q2, what goes unreported is that this is precisely what the number was in the quarters preceding the 2001 recession (2000Q4) and the 2007-09 recession (2007Q3) . . .

[T]he title of a Cleveland Fed report in November 1989, just ahead of the 1990 recession: “How Soft a Landing?” Here was a Market Insight column from December 2000 (the recession began three months later): “Making A Soft Landing Even Softer.” And this was from September 2007, two months before the onset of The Global Financial Crisis published by the Dallas Fed and picked up by Reuters: “US economy on track for soft landing — Dallas Fed.”

The economic data, including corporate earnings reports, have been strong. Confidence is in order. But given the labour market and policy lags, exuberance is not.

No one wants to blow up the leveraged loan market

Last week, we told you about Kirschner vs JPMorgan, an appeals court case concerning whether syndicated bank loans are securities. To recap, in syndications, banks originate loans to indebted companies and then sell slices of the loans on to institutional investors. This is in many ways similar to a company issuing high-yield bonds. But bonds are given the enhanced investor protections of the securities law, and loans aren’t.

In Kirschner, the plaintiff is arguing that loans ought to be treated as securities under the law. JPMorgan, and the bank loan industry, disagrees, and argues that any ruling to the contrary would tangle up a $1.4tn market full of sophisticated players who don’t need extra protection. This seems a reasonable concern. As we wrote last week, “Changing an asset class’s regulatory regime is a big deal. Leveraged lending would presumably seize up as market participants worked out what’s legal and what’s not.”

In any case, it’s a technical dispute with big implications, so the court asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to weigh in. Weirdly, though, the agency last month declined to give an opinion, after seeking several extensions. Now we know why. Semafor reports:

The Securities and Exchange Commission shelved a legal brief that would have required bank loans to carry the same kind of disclosures as stocks and bonds, people familiar with the matter said.

Behind the scenes, Fed and Treasury officials urged SEC Chair Gary Gensler to reconsider his position, the people said. Sweeping corporate loans into the nation’s rubric of securities laws would roil already-shaky debt markets, they argued.

The SEC, perhaps unsurprisingly, was about to submit a legal opinion that would’ve expanded its jurisdiction, but was waylaid by other financial regulators wary of market disruption.

The situation is tricky. The legal case that loans aren’t securities rests on a 1992 precedent called Banco Espanol. In that case, an appeals court decided that what we would today call a syndicated bank loan looks like a traditional loan participation agreement between commercial banks, a clear non-security. The case was decided narrowly on appeals, two to one, brushing aside the SEC’s view at the time that the loans were securities. The chief judge in the case lodged a withering dissent, writing that the decision “misreads the facts, makes bad banking law and bad securities law”, chiefly because it ignores a discrepancy in information. In a loan participation, commercial banks have full information. In a syndicated loan, as we discussed last week, (non-bank) investors can be left in the dark.

Ann Lipton, professor at Tulane Law School, agrees. She told Unhedged:

I don’t know of another situation like this! That’s exactly the dilemma for the [court] and for the SEC . . .

The industry mushroomed on the back of a case that, I would say, was wrongly decided at the time. But even if it wasn’t, the industry’s grown a lot since then and, for whatever reason, the SEC left it alone and nobody bothered to come in and say, “Hey, wait a minute, let’s try again.” Until this case, when at this point [the court] doesn’t want to personally blow up this industry.

Once an asset class grows large, changing its legal status, even if justified, is very hard indeed. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

The economics discipline is warming up to industrial policy.