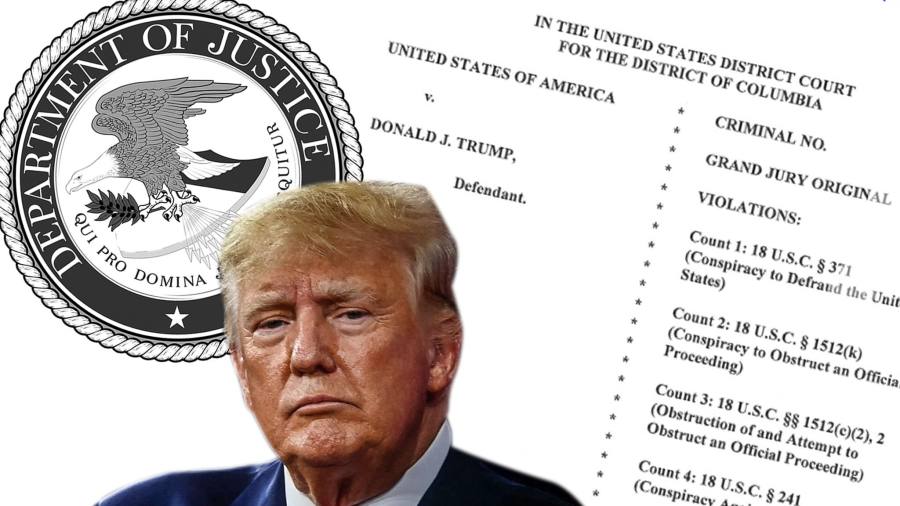

With his second criminal case against Donald Trump, Jack Smith has taken his biggest swing yet. In doing so, the prosecutor appointed to handle investigations into the former US president is entering uncharted legal territory.

The scope of the charges brought by Smith’s team could not be broader, in effect alleging an all-out assault on the peaceful transition of power that is a bedrock of US democracy.

That might make it the most serious legal threat yet for Trump, a frontrunner for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination already under indictment in two other criminal cases. But unlike the other case Smith’s team has brought, over the mishandling of classified documents at the former president’s Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida, it is not necessarily cut and dry.

Among other allegations, Trump is accused of perpetrating a conspiracy to threaten individual rights, based on law first adopted in 1870 to thwart the Ku Klux Klan’s attempts to intimidate voters. He has also been charged with conspiracy to defraud the US, a count normally reserved for financial malfeasance.

“This is going to be a much more legally complicated case [for prosecutors] than the Mar-a-Lago one,” said Joseph Moreno, a former national security prosecutor at the Department of Justice who cited a “very unusual set of facts” and a “novel application of certain broad laws”.

Much of the indictment builds on the work of a bipartisan congressional committee that heard hours of live testimony and read hundreds of pages of evidence about the events between the presidential vote in November 2020 and January 6 2021, when a mob of angry Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol.

However, Smith’s team also appears to have obtained new evidence during the months-long grand jury investigation that culminated in Tuesday’s charges. This included contemporaneous notes taken by then vice-president Mike Pence from a meeting on January 4, during which Trump allegedly made claims of election fraud such as “bottom line — [we] won every state by 100,000s of votes”.

Shortly after the indictment was unsealed, Trump lawyer John Lauro followed a now-familiar script for the former president’s defenders, claiming “political speech now has been criminalised” by President Joe Biden’s administration.

“I would like them to try to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Donald Trump believed that these allegations [of election fraud] were false,” Lauro added.

To some legal experts, building a more challenging case appeared deliberate.

“The indictment reflects a conscious choice to bring the more difficult charges . . .[They] really go to the heart of why it is justified to bring a prosecution against the former president,” said Aziz Huq, professor at the University of Chicago Law School. “It goes to the question of whether [Trump] is committed to the democratic process or whether he is hostile to it.”

Temidayo Aganga-Williams, a former federal prosecutor, said prosecutors could have considered bringing even more charges, such as seditious conspiracy or incitement of an insurrection, which some Democratic activists hoped might have led to Trump being constitutionally barred from standing for office.

Instead Smith’s team has “gone for an indictment that is thorough and precise”, added Aganga-Williams, who served as senior investigative counsel for the House Select Committee investigating the January 6 attack.

Although the 45-page indictment contains detailed accounts of Trump and his team’s alleged attempts to overturn election results in multiple states including Arizona and Georgia, just 11 pages are devoted to the events that took place on January 6.

“I think what they’re trying to get at is that president Trump’s crime here began on election night, and it did not begin on January 6,” said Aganga-Williams.

“They really focus on how much he tried to do that was illegal, that would have been illegal if no one went into the Capitol at all on January 6,” he added. “All these acts did not need violence at the end to be illegal . . . and what happened on the 6th was really a culmination of the failure of all of those attempted political coups.”

Smith’s team detailed the events alleged to have occurred in Georgia at great length, including Trump’s instruction to the Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger and his counsel to “find” 11,780 votes, threatening criminal prosecution if they failed to comply. Those same events are the subject of a second grand jury investigation taking place in Fulton County, Georgia, where a charging decision is expected in the coming weeks.

The indictment also cites six unnamed co-conspirators — four lawyers, a DoJ official and a political consultant, suggesting more people may yet be charged. It would be “odd” for Smith, “having been very specific about the involvement of the unnamed but inferentially identified co-conspirators, to leave them be,” said Daniel Richman, professor at Columbia Law School.

Despite extensive evidence produced by the House committee and grand jury — including hours of video footage — prosecuting January 6-related cases has not always been easy.

For instance, one of the charges against Trump relates to obstructing an official proceeding, which has triggered a fraught legal debate after being used by prosecutors against numerous individuals accused of attacking the US Capitol on January 6 2021.

A federal appeals court in April backed the DoJ’s use of the obstruction charge, but judges have expressed diverging opinions on whether it was applied too broadly and on how courts should interpret one critical word in the underlying law: whether the defendant acted “corruptly”.

Huq, however, argued that proving a corrupt mental state, which suggests misconduct was aimed at personal benefit, may be easier for Trump than for rioters because he “does stand to gain”.

Meanwhile, prosecutors must show Trump knew his claims he had won the election were false, something that could be hard to prove, Moreno said.

“It is not that the prosecutors have to show that a reasonable person knew that they lost . . . they have to show the defendant knew, and Donald Trump is a strange guy,” Moreno said. “He is going to say . . . ‘I thought I won, and it wasn’t fraud’.”