Receive free Global inflation updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Global inflation news every morning.

Inflation has been the hot economic topic of the last two years, but it is a misleading measure when tracking the pain higher prices are inflicting on households.

US annual inflation declined to 3 per cent in June, down from 4 per cent in the previous month and the lowest since March 2021, according to data published on Wednesday. Yet, US consumers are still facing prices 19 per cent higher than in the average of 2019.

The headline inflation rate measures the difference in prices with the same month last year. But consumers tend to compare prices to “normal” levels — and things were not “normal” at all last year. In 2022, food and energy prices were pushed up to historically high levels by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is a flattening out the inflation rate, but leaves real prices still well above pre-surge levels.

So which countries have been hit hardest? We’ve created a chart to show that this is the case in pretty much all richest economies (you can search the country you want in the box):

A fixations on annual price comparison is also tricksy because countries have seen energy prices soar at different times due to varying energy contracts and differences in government’s support packages.

Spain, for example, saw a quicker rise in consumer prices than Germany or France after the start of the war. This means that the latest inflation figure is up to three times higher in the eurozone largest economies than in the Iberian country. But the accumulated effect since 2019 is similar across all major eurozone economies.

The UK stands out for both particularly high annual and cumulative inflation. Not only British inflation is higher than in any other G7 country — at 8.7 per cent in May — but prices are up 22 per cent compared with 2019, the highest accumulated impact of the group.

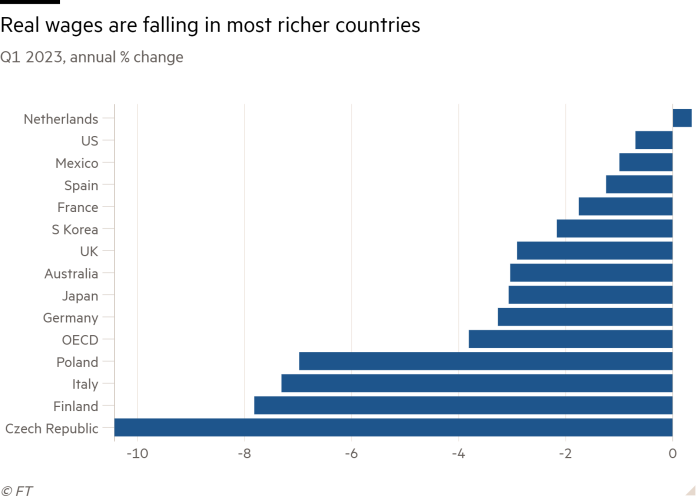

Sure, the inflationary environment will lead to bumper pay increases. But inflation is outstripping wages in 30 countries tracked by the OECD with an average fall in real wages of about 4 per cent across the OECD in the first quarter of 2023. For households, this is effectively a permanent hit to their spending power.

If this isn’t all grim enough, the Bank of England has a tool that lets you play with the cumulative misery effect of rising prices.

It shows that goods and services costing £100 in 2019, had risen to £122 in May. This compares with an increase of less than £8 In the four years to 2019.

There is no doubt that decline in the headline rate of inflation is a step in the right direction for policymakers, but “it far from alleviates these inflationary pressures,” says Victoria Scholar, head of investment at Interactive Investor.

“Households are still struggling from the sharp increase in the cost-of-living and businesses continue to deal with a squeezed margins from higher costs.”