Receive free Life & Arts updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Life & Arts news every morning.

Nathaniel Fick shot to fame when he was featured in Generation Kill, a bestseller about the Iraq war by the Rolling Stone journalist Evan Wright. The book later spawned an HBO series and Fick wrote his own award-winning memoir — One Bullet Away: The Making of a Marine Officer — about serving in Iraq and Afghanistan.

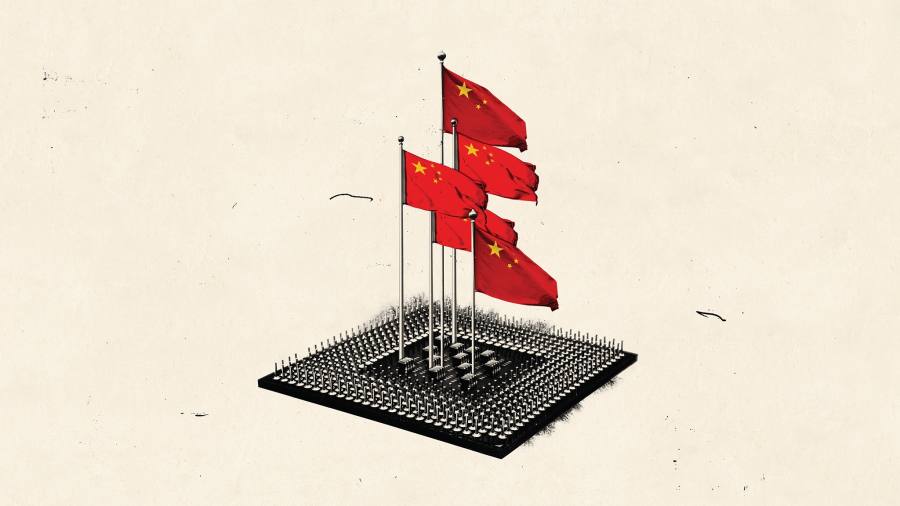

These days Fick, 46, is back on the public stage with a different mission. Last year, the White House quietly appointed him its first-ever cyber space ambassador. That put Fick, who worked in cyber security after the marines, in the role of championing America’s digital interests against countries such as China. He hopes, for example, to persuade US allies to eschew Chinese tech (like hardware manufactured by Huawei) and deter poorer countries from falling into Beijing’s digital orbit.

“We are working around the world to get trusted [western] infrastructure deployed wherever we can,” he told me in Washington recently. A few decades ago, the US and a handful of allies had what felt like an unassailable advantage in telecoms. That advantage has been lost, Fick believes, “due to a combination of corporate distraction, government complacency, Chinese intellectual property theft and subsidies by the People’s Republic of China”.

Fick’s rhetoric is sure to make some roll their eyes. Officials at Huawei, for example, insist American politicians’ obsession with the Chinese telecoms group is misplaced. But whatever you think of that particular case, Fick’s career transition is symbolic of wider geopolitical shifts. Chiefly, it underscores the degree to which US officials are now focused on a perceived threat from China. “It is the most bipartisan issue today,” Dina Powell, a Wall Street financier and former National Security Council official, recently told me.

It also shows how Washington is belatedly waking up to the cost of having paid so little attention to Africa in recent years, while Beijing has intensified its diplomatic focus and invested in the region. One particularly revealing statistic is that China is now the largest bilateral creditor in more than half of developing countries, according to the UK Foreign Office. It lends more than all the so-called Paris Club of western creditors combined.

The other key lesson is the degree to which western diplomats are racing to understand the implications of a world where the internet now risks turning into a “splinternet” — or a locus for geopolitical battles. During the cold war between the US and Soviet Union, it was taken for granted by American diplomats that they needed to learn the language of nuclear proliferation to operate on the world stage. This is still relevant but, when it comes to dealing with tensions between the US and China, “We have realised that we all have to learn the language of digital and artificial intelligence,” as one senior White House official said. Hence Fick’s new role, and why the state department is also putting digital officers into all of its embassies.

Regaining lost ground won’t be easy. Via its Belt and Road programme, China has thrown considerable resources at poor countries to persuade them to purchase its ultra-cheap tech. The US has not hitherto offered similar enticements. What’s more, Washington’s free-market ethos makes it wary of promoting “national champions” in the way that China does. Fick jokes that he spends as much time being a “Nokia and Samsung sales guy” as he does selling Silicon Valley, which is apt to complicate his mission.

Fick has scored some victories. Late last year, US diplomats managed to prevent a Russian telecoms official (who previously worked at Huawei) from becoming head of the International Telecommunication Union, a UN agency responsible for facilitating co-operation between countries. He is currently trying to corral support for western candidates in other global internet bodies too.

And, as he tries to deter poor nations from gobbling up cheap Chinese tech, Fick insists that “the wind is starting to shift” in the US’s favour, since poor nations realise more “about debt trap diplomacy”.

Maybe. The hard truth is that even if countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia are becoming more nervous about the strings attached to China’s largesse, they remain distrustful of the west too. “Africa has been dealing with foreign powers for 500 years,” Mvemba Phezo Dizolele, the Africa programme director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me, noting that “there is a trust deficit” with America, like China, due to

decades of exploitation.

It’s all part of the reality of 21st-century geopolitics. And while Fick’s latest “war” is unlikely to match the vivid plot lines of his time as a marine, it’s every bit as important as previous battles.

Follow Gillian on Twitter @gilliantett and email her at [email protected]

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first