Receive free Human rights updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Human rights news every morning.

The writer is senior fellow for Latin America at Chatham House

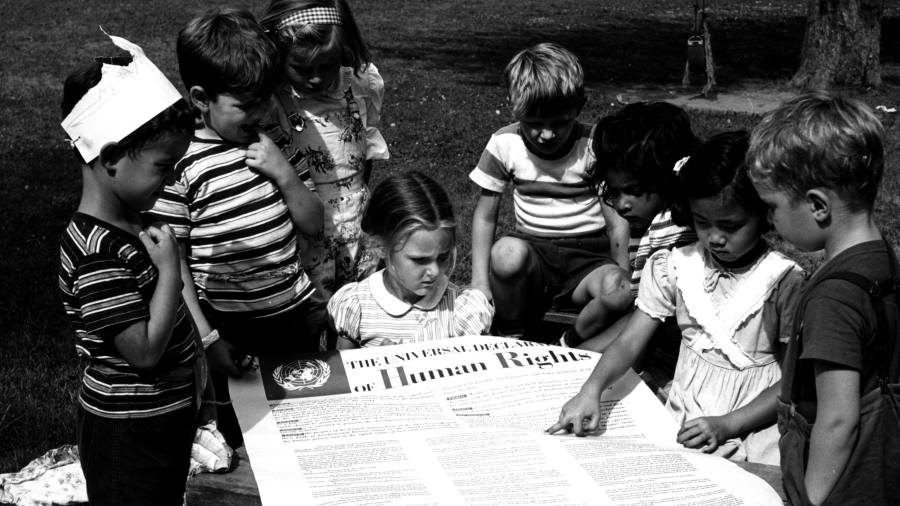

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights — certainly a cause for celebration. But now is also a time to re-evaluate the international human rights framework, which is facing novel challenges. Our freedoms are being weakened by populism and technology, as well as an emerging coalition of autocratic states. It’s time for an upgrade.

Ratified by the UN General Assembly in December 1948, the UDHR committed signatory states to protecting individual freedoms and spawned international and regional laws and bodies to defend them. It also sparked a cultural shift. The idea that states must protect human dignity and individual liberty is now embedded in popular discourse and expectation.

Today, however, an increasing number of non-democratic states are gaining power while undermining the consensus on human rights. These countries are building a rogues’ gallery of allies aiming to tear down what they perceive as an intrusive liberal international regime.

Human rights-abusing regimes have found one diplomatic and economic ally in Beijing. China has allied itself with these partners in the UN Security Council and the UN Human Rights Council, forging coalitions to challenge not just international scrutiny of the treatment of its Uyghur population but also abuses committed in Myanmar, Iran and Cuba and others.

The intent is to muddy global consensus on human rights. The China and Russia-created Shanghai Cooperation Organization, for example, has served as a forum for member states, mostly former Soviet republics in Central Asia, to promote Beijing’s security vision, share model repressive laws designed to curtail political rights and field pro-government “elections monitoring” missions.

In Latin America, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States has reaffirmed “the inalienable right of every State to choose its political, economic, social and cultural system”.

Meanwhile populists of the left and right — including in the developed north — are attempting to undermine confidence in democratic processes. Rightwing figures such as former president Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, former US president Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, and leftwing figures such as Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico and Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela have wittingly or unwittingly collaborated by ignoring international human rights commitments.

The first step in tackling this is to restore the fraying commitment among liberal democracies to the human rights system. This must include voices from the global south. It has been 30 years since the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, which — despite demonstrating shades of dissension to come — resulted in the creation of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. This is an important body which has raised concerns over the repression of rights in countries as diverse as Cuba, Iran, Myanmar and Syria.

In coming years, such an event and platform would help re-engage the global south in discussions. In exchange, liberal democracies should lead the much-needed charge for greater transparency and accountability in bodies such as the United Nations Human Rights Council. Election of members to these bodies should be contingent on states’ human rights records and their compliance with past recommendations or decisions.

Finally, there is a need to understand and address the relationship between declining political support for the rights of migrants and minorities and economic insecurities. Preserving pro-human rights discourse and policy means making the current system responsive to the social and economic rights citizens are currently demanding from their national governments.

On this anniversary, we must consider what needs to be done to save the UDHR from potential irrelevance. This work won’t be easy, but it is vital.