Receive free US interest rates updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest US interest rates news every morning.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Higher real bond yields continue to be the talk of Wall Street. How long can they coexist with a strong economy? That question will loom in the background as second-quarter earnings season begins this week. Pepsi reports Thursday, and a pack of big banks follow on Friday. Expectations are that S&P 500 second-quarter earnings fell 7 per cent from a year ago. If we were betting men we’d take the over, given the effervescent economic backdrop. We’re not betting men, of course, but we are keen to hear about your wagers: [email protected] & [email protected].

Why isn’t the economy responding to rate increases (yet)?

The Fed completed 500 basis points of rate increases in a 14-month sprint, and yet growth is still humming along nicely. The economic slowdown is not dreadfully late, but people are starting to look at their watches nervously and wonder if it is stuck in traffic somewhere, and why hasn’t it at least bothered to call.

The most likely explanation is a delay rather than a no-show. The current lag in policy effects is not hugely long by historical standards. As Don Rissmiller of Strategas put it recently: “We’re holding our breath under water, as long as [monetary] policy remains restrictive.”

But the lag is long enough that we are considering some reasons why this cycle might be different. Here are five possibilities:

Maybe the neutral rate — the real policy rate that neither sparks inflation nor suppresses growth — is higher now. It is hard to measure the neutral rate, but there is cause to think it’s risen since the pandemic. The New York Fed’s widely cited estimate puts it at 1 per cent. But four economists at Vanguard — Joseph Davis, Ryan Zalla, Joana Rocha and Josh Hirt — argue in a recent paper that the neutral rate may be closer to 2 per cent.

This is important because if the neutral rate is indeed higher than 1 per cent or so, monetary policy isn’t that tight. Using Vanguard’s estimate of a 2 per cent neutral rate, back-of-the envelope maths suggest policy only entered restrictive territory around February, and even then only barely. If this is right, policy’s bite could still be a long ways off.

Why would the neutral rate have risen? The Vanguard team points to the $1.5tn fiscal deficit. Sustained fiscal shortfalls increase economy-wide demand for borrowing, pushing up nominal interest rates. Roger Aliaga-Diaz, head of portfolio construction at Vanguard, gave us four further reasons to suspect a higher neutral rate:

-

The massive global fiscal impulse which was needed to restart the global economy after Covid has ended a decade of secular stagnation.

-

The massive issuance of government debt after Covid may have alleviated the scarcity of risk-free assets that some think kept rates low.

-

The “savings glut” — low rates driven by global imbalances and current account surpluses in emerging countries like China and advanced economies like Germany — is subsiding. In particular, China’s current account balance is closer to zero now.

-

New demands on developed-market governments suggest more borrowing is coming. Think defence budgets increasing, green investments, energy independence, industrial policy and the shortening of supply chains.

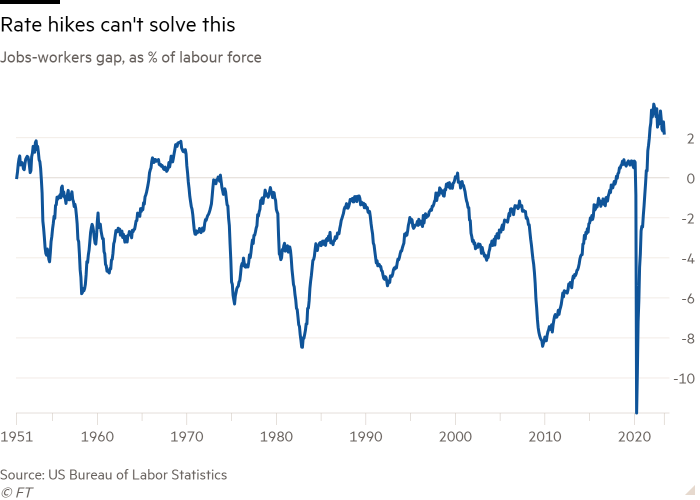

The labour shortage could be so severe that rate hikes don’t hurt employment much. Without a rise in unemployment, the economy can’t really fall into recession. But a structural labour supply shortfall and the recent trauma of companies struggling to find workers during Covid could be leading to labour hoarding. The “jobs-workers gap”, the sum of job vacancies and employed people minus the number of workers in the labour force, is the widest on record:

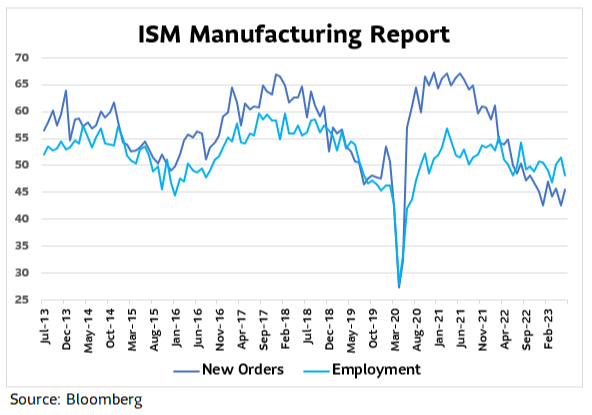

Dec Mullarkey of SLC Management points out that employers, rather than shedding jobs, have been cutting hours. Average weekly hours in the monthly payrolls numbers have fallen back near to pre-pandemic levels — which can’t be said of job or wage growth. He adds that manufacturers in the monthly ISM survey are showing similar labour-hoarding tendencies. The new orders and employment sub-indices, which usually travel together, have come apart. Even though activity has contracted sharply, employment hasn’t (Mullarkey’s chart):

Debt has been “termed out” in recent years, so higher rates have less economic impact than they once did. This seems to be true for both consumers and corporations.

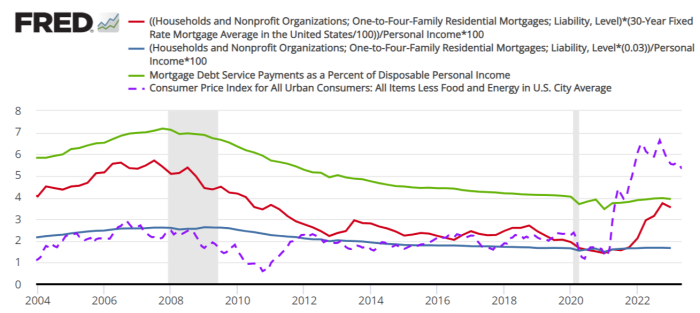

The fall in the proportion of mortgages that are adjustable rate and the stampede to refinance mortgages while rates were very low means that higher mortgage rates have not had a large impact on the interest costs of households. This point is made concisely in a recent post from the St Louis Fed. It points out that if all household mortgage debt in the US were readjusted to the current mortgage rate, interest payments as a percentage of income would have more than doubled (red line below). But in fact, since the start of the pandemic, mortgage interest as a percentage of incomes has risen hardly at all (green line). Incomes have risen enough to offset the aggregate impact of new, higher-rate mortgages:

Of course, the aggregate data glosses over distributional impacts. If you had to move recently, your new mortgage rate stinks. Just as importantly, higher rates have made people disinclined to move, killing the existing home market and creating an economic drag. But most households are not feeling much impact.

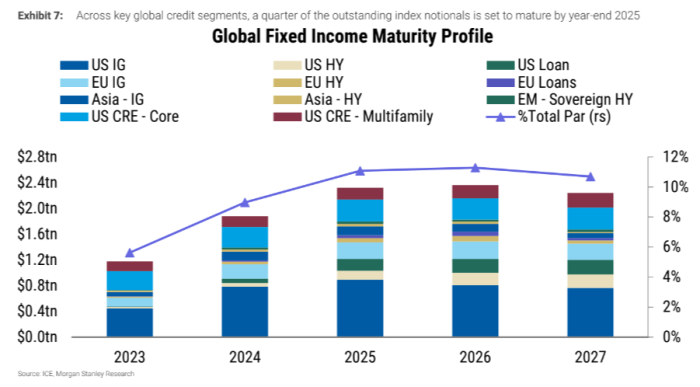

Companies have added a lot of leverage in the last decade. Corporate debt has grown about three percentage points a year faster than nominal GDP (8 per cent versus 5 per cent). But many companies took advantage of ultra-low rates up until 2021 to push out maturities. This chart from Morgan Stanley shows that only about 15 per cent of global corporate debt matures before 2025 (if you have a neat chart or data set for the US only, send it along).

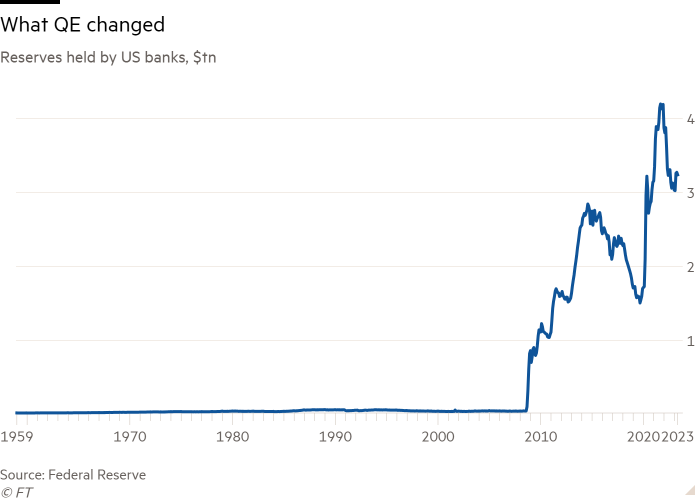

Under an “ample reserves” regime, monetary policy transmission is diluted. Quantitative easing changed the prevailing monetary environment from one where money is scarce to one where it is abundant. Just look at the quantity of reserves banks hold at the Fed:

This slows the pass-through between higher policy rates and higher deposit costs. The usual urge banks feel to keep deposit rates competitive is damped by the simple fact that funding is everywhere. With one-year Treasuries at 5.4 per cent, Bank of America is still offering a measly 0.01 per cent on its savings accounts and the national average one-year CD pays just 1.6 per cent. Cheap funding keeps net interest margins plump, lifting lending. While loan growth has slowed, it still grew 8 per cent year-over-year in May. Even economically sensitive commercial and industrial loans expanded 6 per cent.

Perhaps modern services-based economies can largely shrug off rate increases. Rick Rieder of BlackRock makes this point in a recent note. He argues that economies led by services consumption, like the US, are less levered to monetary policy than are investment-led economies like China. Except during cataclysms like 2008 and Covid, US output tends to march ever higher. Rieder writes:

[A] modern advanced economy, like that of the United States, doesn’t see such cycles in quite the same way as it did in the past, and that technology, better inventory, payments, collections and employment tools have tended to dull economic volatility…

When one looks at the history of nominal GDP over the past 30 to 40 years, it looks like a fairly smooth path to higher economic wellbeing . . . One [reason] is the relative stability of consumption as the primary proportion of the economy, which is to say that consumption doesn’t really adjust that dramatically without some major form of economic stress . . . This is in contrast to an investment-led economy, such as that in China, which requires large amounts of capital, and generally debt financing, to drive economic growth

We need to think about these explanations more before we endorse any of them wholeheartedly. Even supposing one accepts them, however, an important question remains. Do factors that blunt or delay the effect of monetary policy increase the odds of a soft landing — that is, lower inflation without recession? Or do they mean the Fed just has to squeeze harder, leaving recession delayed but not avoided as the most likely outcome? (Wu & Armstrong)

One good read

John Plender on the lessons from the long bull market in bonds.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

The Lex Newsletter — Lex is the FT’s incisive daily column on investment. Sign up for our newsletter on local and global trends from expert writers in four great financial centres. Sign up here