Surfers flock to Thurso on Scotland’s northern coast every year to ride the big waves generated in the Pentland Firth, one of the most dangerous stretches of water in the world.

But the attraction of the most northerly town on the British mainland could become more mainstream under a radical proposal to put the UK on the path to net zero: some of the cheapest wholesale electricity prices in Europe.

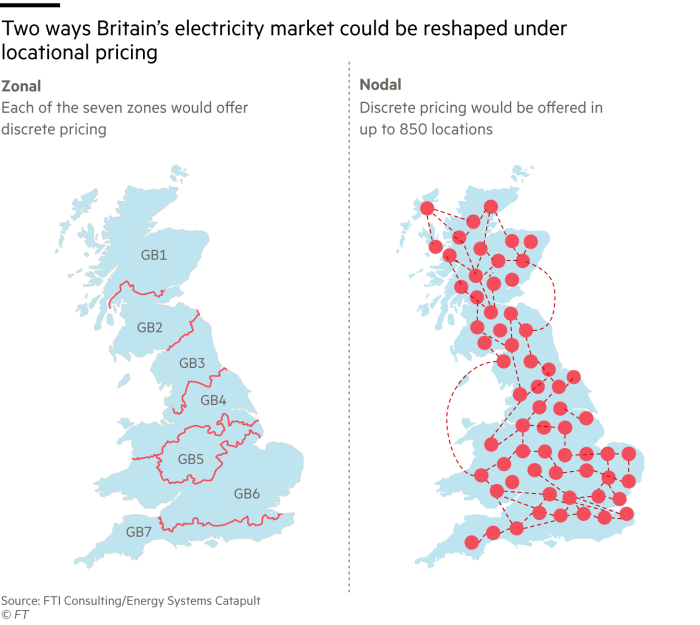

If implemented, the changes would split Britain’s electricity market into seven charging zones or hundreds of different nodes to try to make the network more efficient, leading to large variations in price depending on proximity to generation.

The concept, known as “locational pricing”, is one option being considered by industry regulator Ofgem and the government as part of a plan to decarbonise the grid by 2035.

Its proponents argue that the most radical model could redraw the industrial map, encouraging more wind turbines to be built in the south of England and encourage new green industries, such as gigafactories and hydrogen electrolysis, in Scotland, which is by far the biggest producer of renewable energy in Britain.

But the proposed reforms are controversial with energy investors and face questions over the model’s fairness and effectiveness.

Even the Scottish government has yet to be convinced, despite the potential advantages.

“[Locational pricing] offers theoretical benefits for consumers, but much more work is needed to understand how those benefits could be secured,” said Gillian Martin, Scotland’s energy minister.

The reforms are being considered as part of efforts to tackle the escalating costs of managing the electricity grids as less predictable renewable generation replaces fossil fuels, along with a growing mismatch between where electricity is generated and where it is most needed.

Supply and demand has to be constantly matched to avoid blackouts, but this is becoming more difficult with limited capacity to move electricity from Scotland to areas of high demand in England.

National Grid’s electricity system operator spent £1.9bn last year on “constraint costs” such as paying wind farms to turn off. It has warned that without reform there would be a “dramatic and accelerating” increase in these costs, which are funded by consumers.

It believes a shift to the nodal locational pricing model is the best solution to keep costs down. A recent report by FTI Consulting, commissioned by regulator Ofgem, found the move could save £48.8bn in accumulated network costs by 2040.

The same study found that zonal pricing would have much less of an impact on network costs, a view shared by National Grid, which said it was only a “partial and temporary solution”.

The modelling for nodal pricing shows significant regional variations in average annual wholesale rates. Scotland, northern England and northern Wales will have prices “among the cheapest in Europe” with Thurso some of the lowest of all. In contrast, the south of England will have the highest in Britain.

Under FTI’s most extreme pricing scenario the annual average wholesale cost of electricity would range from £37.00 per megawatt/hour up to £58.70 per MWh by 2040.

Ben Houchen, the mayor of Tees Valley in north-east England, said the lure of cheap energy could be transformational. “It is feasible to see areas like mine much better off from a cost-of-living viewpoint as well as from a re-industrialisation viewpoint.”

But heavy industry appears less convinced. “Existing assets, access to raw resources and closeness to final customers are bigger reasons to locate,” said Arjan Geveke, director of the Energy Intensive Users Group.

The radical proposal has been rejected by SSE, one of Britain’s biggest clean energy investors, which argues the move would make revenues far harder to predict, pushing up the cost of capital. Generators would also no longer be entitled to compensation if they were unable to produce electricity due to network constraints.

“The 2020s needs to be a decade of delivery,” said Alistair Phillips-Davies, chief executive of SSE, which is planning to invest up to £40bn by 2030. “Evolution of market design is the way to take investors with us. Experiments will scare them away.”

Pushback from clean-energy companies on similar grounds led to the recent rejection of full locational pricing in Australia. “The message came across pretty resolutely,” said Christiaan Zuur, at Australia’s Clean Energy Council.

Even if the model was embraced in Britain, it would not necessarily mean the geographically variable wholesale costs would be passed on to businesses and households. Retailers could give consumers the choice whether to be exposed to the half-hourly fluctuations in price.

Countries that already use it, such as New Zealand, have adopted this type of approach.

“There is a question of fairness if different regions are paying different wholesale prices,” said Andy Manning, principal policy adviser at Citizens Advice.

There are benefits to variable consumer pricing, according to Ofgem. “It could enable consumers that can be flexible to behave in a way that is most beneficial for the system and to be appropriately compensated,” it said.

This would help drive much-needed behavioural change by encouraging consumers to charge items such as an electric car at times when prices were lower, for instance.

Octopus Energy, one of Britain’s largest energy suppliers, is keen to see the model introduced. “Not everybody needs to participate to get some very significant savings overall,” said Rachel Fletcher, its director of regulation.

Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, where consumers would face some of the highest electricity prices in the country, was more cautious. He called for “all options [to be] considered and evidence presented to understand the proposals, and the impact they will have on Londoners”.

The government said locational pricing was just one option and it would always “aim to ensure a fair deal for consumers”.

Given the rising costs of managing the existing system, it seems inevitable that something will have to change. “Doing nothing is not an option,” said Manning. “We would have to have a viable alternative before taking locational pricing off the table.”