A year and half into the war, Ukraine’s counteroffensive against Russia might not look particularly impressive on the map, but at the front, it’s clear that progress is being made — albeit slowly.

More than three weeks since the long-awaited summer offensive began, Ukraine has only retaken a handful of villages along the southern frontlines, as confirmed by geolocated photos and videos. The bulk of them are south of the village of Velyka Novosilka, which CBC visited alongside Ukraine’s 68th Brigade.

The front lines themselves are divided into two areas. On the line of contact itself, Ukrainian troops hammer Russian defenders with constant assaults, keeping the pressure up and searching for weak points.

Seven or eight kilometres back, artillery continues its deadly work. During a recent visit to the front line, a French-made CAESAR self-propelled howitzer emerged from a nearby forest to set up on a crossroads, firing five shells in as many minutes before moving yet again to evade any Russian response.

“We are always searching for weak points in their lines,” said a 33-year-old Ukrainian soldier who goes by the call sign Excalibur. “When we find one, we go for a breakthrough. The assault units gather on foot, supported by tanks and other military villages. Once we break the first point, we move to encircle the village and then clear it.

“Any Russians left there are either killed or taken prisoner,” Excalibur said.

All of the Ukrainian soldiers interviewed only identified themselves by their call sign or first name, as per the army’s restriction for active-duty military personnel.

In this sector of the front line, the Ukrainians are in full attack mode, something underscored by their use of artillery.

“[The artillery] now is firing in front of the advancing infantry,” said another Ukrainian soldier with the call sign Khomiak. “They are hitting the Russian positions in Urozhaine [the nearest Russian-held village], which our guys are trying to liberate.”

Russia’s 1st line of defence ‘especially strong’

The assaults themselves are not easy. Satellite imagery shows that the Russian lines consist of many overlapping defences, ranging from minefields to fortified machine gun nests to anti-tank ditches and barriers. Ukrainian troops must navigate and overcome these hurdles under a hail of artillery and small arms fire.

“[The Russians] have had this area for over a year,” Excalibur said. “They had time to entrench, to build concrete fortifications and place mines. The first line of defence is especially strong.”

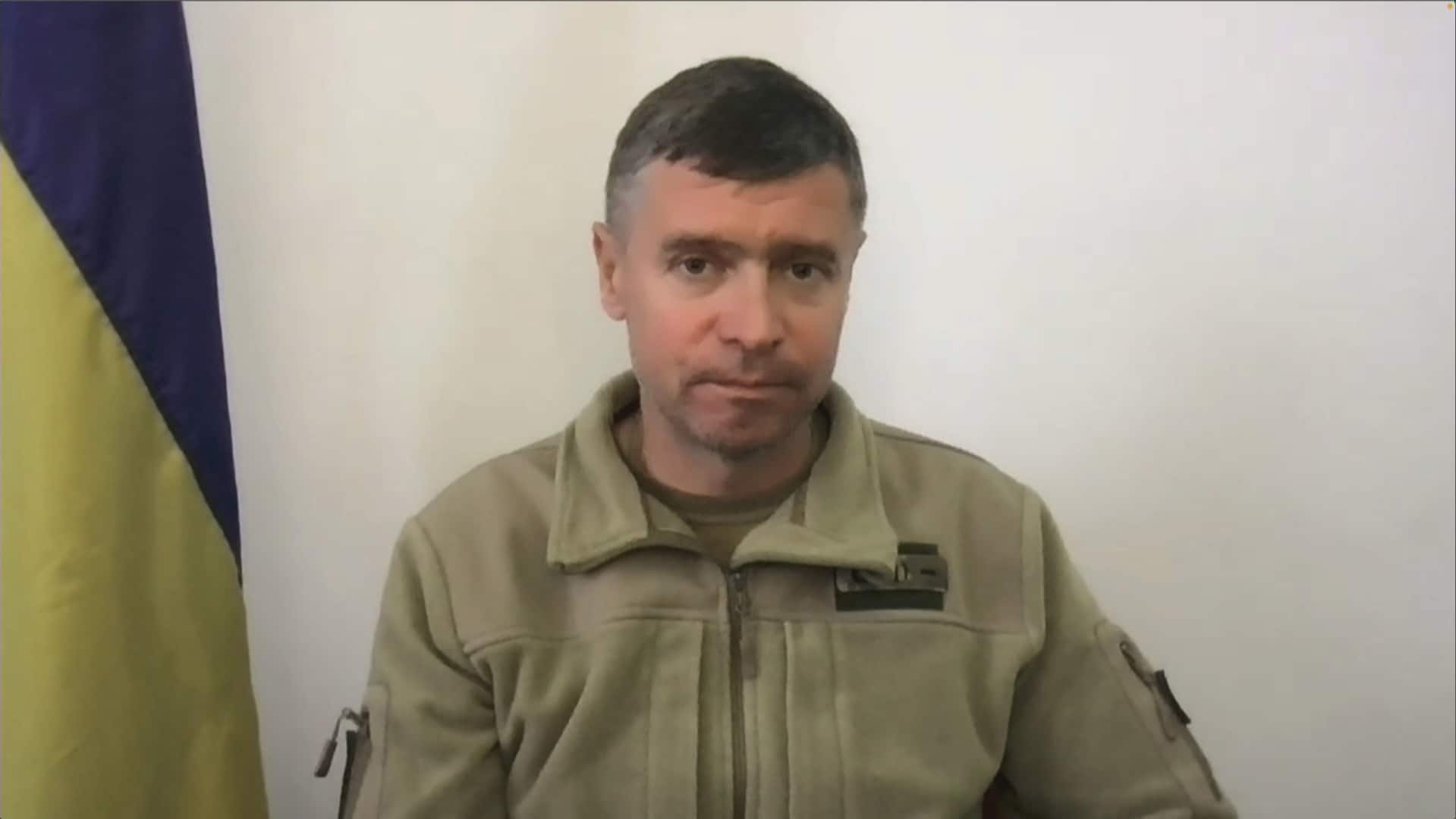

WATCH | Ukraine’s defence ministry explains its counteroffensive:

Yuriy Sak, adviser to Ukraine’s defence minister, told CBC’s Rosemary Barton Live Ukraine is moving forward with a counteroffensive strategy against Russia in some areas of the expansive frontline, including the Bakhmut region.

The difficulty of such head-on assaults was exemplified by a now-infamous column of Western-donated armoured vehicles that was destroyed on June 8, including numerous Bradley infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) and at least one Leopard 2 tank. That has led to a need to hit Russian forces from the flanks wherever possible.

“The best [approach] is to bypass [the frontal defences] and hit them from the side,” Excalibur said. “That’s what we do: reconnaissance by force. We go in, make contact, then if they are entrenched, we pull back and try another spot. There is always some place where they will crack.”

These probing tactics are part and parcel of Kyiv’s approach to the offensive. Long-range missile strikes have focused on Russian command posts and logistics nodes, rather than front-line units.

A recent New York Times article reported that Ukraine is yet to deploy most of the 40,000 Western-trained and -equipped troops it had shepherded for the campaign. The 68th Brigade itself has been in action for almost the entire war, defeating a major Russian armoured assault on the town of Vuhledar in February.

Loss of many experienced soldiers

While victorious, the battles over the winter took their toll on the 68th — particularly in terms of experienced soldiers.

A battalion commander in the 68th who goes by the call sign Dolphin describes losing one-quarter of his unit’s combat personnel in the winter months.

“From November through February, the enemy attacked again and again, near Vuhledar and Pavlika,” Dolphin said. “My unit took [one of the main] roads under control and didn’t let the enemy approach, but there were a lot of losses. Out of 420 soldiers, we lost 100 killed and injured, including, unfortunately, the best ones.”

Despite those heavy losses, the 68th was given a leading role in the ongoing offensive. Another brigade, the 72nd, was transferred to hold the Vuhledar sector as the 68th moved from defence to offence. The 68th has achieved some results, liberating the village of Blahodatne on June 11.

Dolphin himself bears several small injuries from recent battles, his right eye and right arm a testament to the hard fighting.

The 68th is still licking its wounds. A group of 25 draftees, brought in to replace those lost of the winter, is currently receiving a crash course in battlefield tactics, learning whatever it can over the course of just two weeks before deployment.

“It reminds me of the Germans in 1945,” Dolphin said of these still-green recruits, who will be on the front lines in less than a week. “Here is a group that has never served. Two weeks are not enough, but we don’t have time.”

The challenge of air superiority

Judging the success of the present offensive is difficult for the soldiers involved, let alone outside observers.

Ukrainian forces have used long-range missiles to severely damage Russian logistics, destroying massive ammunition depots and critical rail bridges. Shortages in modern Russian equipment are also becoming evident, with T-54 tanks — first introduced in 1948 — now appearing on the battlefield.

But territorial gains have been minimal. After liberating a string of villages in mid-June, Ukrainian forces have struggled in the past two weeks to push the line forward. In a June 30 interview with the Washington Post, the head of Ukraine’s general staff, Valery Zaluzhny, expressed frustration with Western partners, saying he is forced to carry out an offensive under conditions that NATO countries would never accept themselves — namely, a lack of air superiority.

On top of the prepared Russian defences, Ukraine’s attack troops face another challenge: Russian helicopters.

A Ukrainian special forces soldier named Pavlo has just returned from two weeks of fighting on, and behind, the front lines. He describes the threat posed from the air.

“There is constant fire [on us], from both helicopters and fighter jets,” Pavlo said. “The helicopters stay eight and a half kilometres back, hovering above the trees. We only have Stingers [shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles], with a range of four kilometres. Just one helicopter hit [our positions] 20 times in one day.”

Still, the mood among the soldiers of the 68th Brigade is good. Morale is high, as is a sense that the Russians are taking heavier casualties than they are — and responding to them in a worse way.

“We have taken a lot of prisoners,” Excalibur said. “They have plenty of convicts serving, guys who don’t want to fight, so they often surrender.

“For us, of course, we have some guys who aren’t handling [the stress] well, but most of us are still smiling and laughing. We knew this would be a long fight.”