Receive free EU enlargement updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest EU enlargement news every morning.

This article is an on-site version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Good morning from (blisteringly hot) Madrid, where Pedro Sánchez’s government is juggling the start of Spain’s six-month rotating presidency of the EU with campaigning for a general election in 19 days that could see him turfed out of office.

Today I explain why Sánchez (or his replacement) will oversee the first serious debates on restructuring the EU to make it fit for expansion, while my environment colleague has news on Europe’s potential to stuff carbon dioxide into the ground.

The enlargement presidency

Spain’s presidency swung into action yesterday facing a daunting to-do list. But top is the biggest question of all: What is the future of the European project?

Context: Russia’s war against Ukraine has reignited previously stone-cold efforts of EU enlargement, provoking both the applications of Ukraine and Moldova and reinvigorating work on pushing ahead with the accession processes of the six Western Balkan countries.

Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s prime minister, was explicit about the task ahead. “Enlargement is on the table,” he said, before listing all of the things that first need to be sorted out, from the size of the European Commission to the amount of cash given to farmers.

Sánchez has a decent idea of what’s coming — and where the faultlines will lie. He sat down for breakfast on Friday with the other leaders of the EU’s 10 biggest states by population to sketch out initial thoughts on how a bigger bloc would work.

And he — or his successor as prime minister — will host a summit in Granada in October where the topic will be chewed over in detail.

While some capitals are keen for fast-track processes to bring the candidates into the western fold, others are wary about lowering the bar and diluting the bloc’s standards. Spain’s approach will be “realistic but credible”, one official said.

Ursula von der Leyen, commission president, was unequivocal.

“Let’s look forward for years and try to imagine what Europe will look like. Can we imagine the European Union will be without Ukraine, without Moldova, without the western Balkans? And those parts of Europe will be under the influence of Russia, or China? Impossible,” she said.

“So the direction of travel is clear. And therefore now we need to think about how we are making sure that Europe is whole,” she added. “We have to discuss how the decision-making process will look, we have to discuss how the common funding that we have will be allocated.”

There was even a flick at speculation whether von der Leyen will remain as president after her five-year mandate ends next summer. “Irrespective of what my future is, we need to address [these questions] as soon as possible as it will take time to reach a conclusion,” she said.

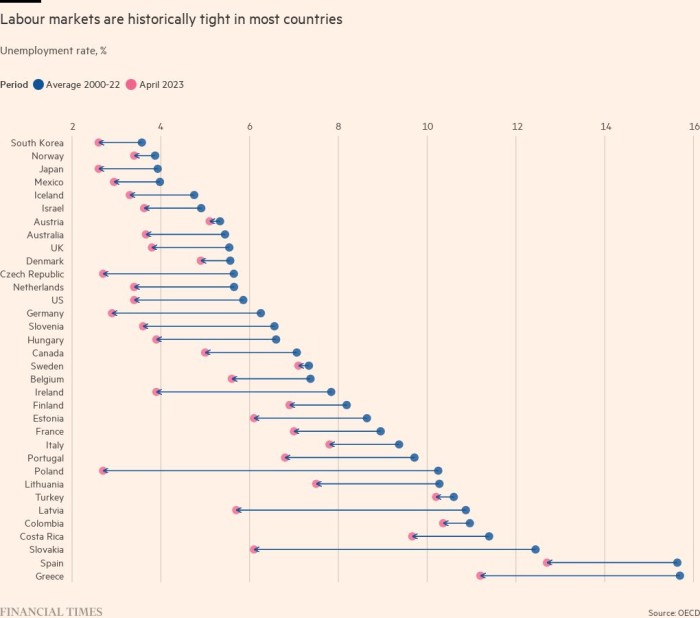

Chart du jour: Strong labour

With low unemployment, many countries struggle with labour shortages — especially in the services sector. This has boosted wages and could help explain why inflation persists, despite the European Central Bank’s rate rises.

Underground solutions

The EU could build storage for up to 1,520 gigatons of carbon dioxide emissions, according to a new study published today.

That is roughly equivalent to 470 years of the EU’s carbon emissions at the rate it emitted in 2021, writes Alice Hancock.

Context: recent assessments of the EU’s ability to meet its climate targets have been bleak. The EU has cut its greenhouse gas emissions by almost a third since 1990, but must hit a 55-per cent cut by 2030. Last Friday, most EU countries failed to submit plans to hit that target on time.

Carbon capture, a process in which CO₂ is siphoned into underground storage, is increasingly seen as a vital part of reducing emissions.

The report by the organisations Clean Air Task Force and Elements Energy lays out the potential for underground storage capacity. It also looks at where and what infrastructure will be needed to move waste CO₂ around.

Large industrial emitters such as cement, chemicals, iron, steel, paper, refining and waste management sectors could especially benefit from the storage, the authors said.

But it is not clear that the sites will be set up where they are needed most.

According to the report, Norway has a large capacity and could store most of its carbon output for up to 36,000 years. Austria has only 29 years worth of capacity, and will probably have to export most of its emissions, the report finds.

And that is only if projects get off the ground.

Carbon capture and storage needs heavy investment, and not all policymakers and environmental campaigners are convinced that it is a solution for climate change, fearing that it will distract from the key task of cutting greenhouse gas emissions overall.

What to watch today

-

Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte and Luxembourg premier Xavier Bettel travel to Kosovo.

-

EU commission vice-president Frans Timmermans is in China for climate talks.

Now read these

Recommended newsletters for you

Britain after Brexit — Keep up to date with the latest developments as the UK economy adjusts to life outside the EU. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe