B.C.’s largest recorded wildfire is burning through the traditional territory of three First Nations, destroying everything from graves to hunting grounds and culturally significant landmarks.

“It’s very heartbreaking. I’ve seen some of our people tear up and cry from that,” says Timber Bigfoot, a member of the Prophet River First Nation and the community’s land and environment manager.

He calls the Donnie Creek wildfire “catastrophic.”

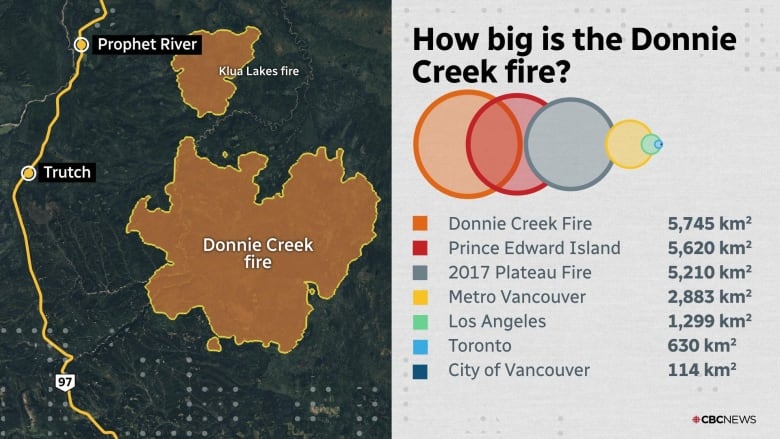

The fire is now bigger than Prince Edward Island.

It’s burning more than 100 kilometres away from the communities of both Fort St. John and Fort Nelson.

Although the area is sparsely populated, Bigfoot said his First Nation has had a deep connection to the land in the fire zone from time immemorial.

“My family for multiple generations was born out there, and we have burial grounds there. We have history here.”

In June, just days before the wildfire threatened to close the Alaska Highway, Bigfoot and his mother drove through the area and surveyed the Trutch Valley.

“She was telling me stories about when she was a young kid driving the Alaska Highway and where they would stop and have sandwiches at the lookout.”

When Bigfoot and his mother looked out over the valley, he said his mother told him she’d love to build a trapping cabin there, among the pines.

Now, Bigfoot said, “It’s all burned. It’s completely gone. You have all this peace and quiet and scenery, and within days, it’s completely burned to the ground.”

The list of his community’s wildfire losses is long: Trappers’ cabins and trap lines. Hunting and fishing grounds. Archaeological sites and traditional trails. Rare diamond willow that’s gathered for ceremonial smudging. Cranberries, huckleberries and blueberries. Beaver, wolves, moose and elk.

“We’re very close to the animals, and it’s very heartbreaking to know that not only is their forest gone, but that many animals have lost their lives, and to know those animals suffered.”

The fire is also burning in the traditional territories of the Doig River First Nation and the Blueberry River First Nations.

“Our members’ way of life has been heavily impacted by this fire,” said Blueberry River First Nations Chief Judy Desjarlais. “

“Our major concerns are for the animals that have left the territory.”

In May, her community was forced to leave their homes under an evacuation order as a different fire, the Stoddard Creek fire, burned dangerously close. No one was injured, and when band members returned home, their community was untouched.

Now, the Donnie Creek fire is burning far from their homes, but Desjarlais said it’s destroying culturally and ecologically important areas where members practise their treaty rights, including hunting, fishing and trapping.

“Our cultural and traditional landmarks could be destroyed,” she said.

The Donnie Creek fire is also burning through land used by industry.

There are oil and gas wells, pipelines, gas plants, compressor stations, resource roads, and work camps.

The BC. Energy Regulator said 24 energy companies have suspended operations and removed their workers because of the Donnie Creek fire.

The Donnie Creek fire is also burning through forests where Canfor and Louisiana Pacific log trees for their mills in Fort St John.

“It’s too early and the wildfire’s too erratic to get a clear understanding of the impacts,” said Rosemary Silva, senior adviser of external relations for Canfor.

Ignited by a suspected lightning strike on May 12, the Donnie Creek fire now covers more than 5,000 square kilometres, with a perimeter of approximately 800 kilometres at the end of June.

The B.C. Wildfire Service said the Donnie Creek fire is expected to burn through the fall and possibly into winter.