Receive free Non-Fiction updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Non-Fiction news every morning.

In the absurd alternative reality Vladimir Putin’s propaganda machine has constructed in Russia, it is his army that is fighting the fascists. Kyiv’s troops, not Moscow’s, are the ones committing atrocities. Even after last weekend’s aborted armed insurrection by Russian warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin and his Wagner paramilitaries, Putin suggested that Russians killing Russians was exactly what the “neo-Nazis in Kyiv and their western patrons” wanted.

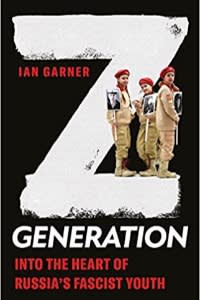

Ian Garner has no doubt who the real fascists are. His book Z Generation is a vivid and disturbing account of how Putin’s regime has brainwashed portions of Russian youth into embracing what Garner portrays as a messianic cult.

“Fascism” is never a term to be thrown about lightly. Even before the Ukraine war, though, as the historian Timothy Snyder has noted, Putin’s Russia had fascist features: a strongman leader atop an authoritarian regime glorying in a heroic past — the victory over the Nazis in the second world war.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has provided the final ingredient: a cleansing war of violence, against the Kyiv leadership and its alleged western puppetmasters, aimed at restoring Russia’s imperial grandeur. It even has its own swastika-like symbol, the “Z” first used to distinguish Russian military vehicles in Ukraine but now ubiquitous.

A strength of Garner’s book is that it is based around social-media engagement with “ordinary” Russians. It describes not just the mechanisms used to indoctrinate kids as early as primary school but how individuals have been sucked into the Kremlin’s parallel universe. It is hard to read it without Orwell’s doublethink or the Two Minutes Hate coming to mind.

So we meet 19-year-old Alina from the Urals rust belt, whose timeline was once filled with make-up and nail design videos but now contains images of a burning White House in “Fashington DC” and rails against “Ukrofascists” as “rabid dogs”. Then there is Maria, a 14-year-old devotee of Putin’s Youth Army, or Yunarmiya, whose members parade in khaki fatigues and learn how to strip Kalashnikovs and prepare for nuclear attack. Or there is Ivan Kondakov, an aerospace engineer and a father of three, who progresses from posting patriotic comedy songs in lockdown to hosting a racism-filled show on a conservative TV channel.

In a pacy read, Garner — a researcher on Soviet and Russian war propaganda — shows how young Russians are bombarded with messaging that their own unique civilisation has a mission to confront an immoral west. A bastion of Orthodox Christian family values, its code is one of militarism, patriotism, physical fitness, and masculinity — and of violence as a purifying force.

To inculcate that vision, the Kremlin has co-opted everyone from the Orthodox church to state media, teachers, sports and cultural figures and other influencers. The chief of staff of Yunarmiya is Nikita Nagornyy, a photogenic Olympic gymnast.

Garner’s mode of research has limitations. Though the arrest of the Wall Street Journal’s Evan Gershkovich has highlighted the dangers of on-the-ground reporting, contacting interviewees online means subjects may be somewhat self-selecting: the most enthusiastic believers, or those happy to be seen as such.

The author does engage with some who have courageously sided with the opposition. But he cannot give a sense of how widely spread and deep-rooted the Putinist belief is among the young, or the extent to which it is performative, or a form of doublethink. The answer to that question is important — to judge how much this is still Putin’s personal war, or one his people have been hypnotised to accept, and hence how durable both the military campaign and the fascist brainwashing may prove.

Garner warns relations may be poisoned for years to come. But his final pages note that just as the late Soviet system proved unexpectedly brittle, so Russia today could prove “closer to the USSR of 1989 than the Germany of 1939”. That suggestion has added resonance after Prigozhin’s armed march on Moscow last week.

Before his rebellion, the former Putin ally debunked Moscow’s narrative for its invasion: Russia, he said, had faced no imminent threat from Ukraine, and was now killing “ethnic Russians” in the Donbas. It is not clear how many Russians saw it — or how many more such videos it might take to sweep away the web of nationalist lies spun by the Kremlin.

Z Generation: Into the Heart of Russia’s Fascist Youth by Ian Garner, Hurst Publishers £25, 256 pages

Neil Buckley is the FT’s chief leader writer

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café