Global asset managers are slashing their valuations of high-profile Indian start-ups in their portfolios, with writedowns approaching 50 per cent for former investor favourites such as tutoring company Byju’s and food delivery service Swiggy, US securities filings show.

The new estimates highlight the changing fortunes of Indian start-ups after a boom in 2021 and early 2022 created 60 so-called unicorns valued at more than $1bn. They also set the stage at lossmaking companies for so-called down rounds, in which financings are done at lower valuations than before.

“Start-ups are cutting costs and staying put, but when they eventually hit the market to raise funds, down rounds will happen,” said Rutvik Doshi, managing director at venture capital firm Athera Venture Partners.

Recent filings to the US Securities and Exchange Commission show that Invesco and BlackRock cut their valuations of Byju’s from $22bn to $11.5bn and of Swiggy from $10.7bn to $5.5bn.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

Subscribe | Group subscriptions

Vanguard reduced ride-hailing start-up Ola’s valuation by about 35 per cent to $4.8bn, while financial services start-up Pine Labs had its valuation cut 40 per cent to $3.1bn by Neuberger Berman. Janus Henderson halved healthcare start-up PharmEasy’s valuation to $2.8bn.

The markdowns compound trouble for Indian start-ups, many of which have sacked workers and cut marketing spending and consumer discounts to conserve capital.

Venture capital investors bought start-up stakes at lofty valuations in the world’s most populous country in the hope that a burgeoning middle class would lead to a spurt in consumption. Indian start-ups also benefited from a comparison with China, where the government’s regulatory crackdown on technology companies raised concerns among global investors.

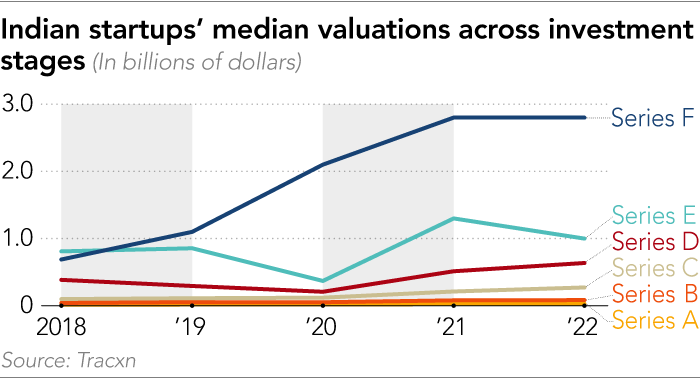

Data group Tracxn estimates the median valuation of Series A — or first institutional-round — deals in India rose 68 per cent from 2019 to $30mn in 2022. Series B start-ups were valued at about $84mn, 58 per cent higher than 2019. So-called growth-stage deals were equally expensive, with Series C valuations jumping 141 per cent over 2019 to $273mn, while Series D valuations soared 116 per cent to $636.8mn.

Flush with funds, start-ups spent lavishly on marketing. Byju’s paid to put its name on the jerseys of the Indian cricket team and was one of the sponsors of the Fifa World Cup. Swiggy and fantasy sports platform Dream 11 were among the sponsors of Indian Premier League cricket.

According to advertising agency Madison, India’s top 50 advertisers in 2021 included 15 start-ups in sectors such as education, financial services, fantasy sports and cryptocurrency. Byju’s and Dream11 outspent such global powerhouses as Procter & Gamble, Mondelez, Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Nestlé.

With funding prospects diminishing, start-ups are now reducing discounts, threatening their ability to attract more consumers, and shutting down fledgling business lines.

Swiggy shuttered its meat and premium-grocery delivery service. Ola closed its food and grocery businesses. SoftBank-backed ecommerce company Meesho stopped delivering groceries. Online education start-up Unacademy shut down its primary and secondary school business.

“The growth rate has slowed down because start-ups are building more sustainable businesses and giving less discounts,” said Brij Singh, general partner at venture capital firm Rebright Partners. “Consumers in India have been very heavily influenced by discount-led models. And without VC-funded discounting, it is tough to grow businesses in India.”

Some large start-ups are looking to raise funds by issuing convertible notes giving investors the right to change the securities into equity during their next fundraising round — a way to bet that their valuations will be higher by that time. Unicorns such as social media firm ShareChat and online wholesaler Udaan have taken that route in the past.

“Many start-ups are cutting costs and have healthy economic models,” said Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder at investment bank IndigoEdge. “But, if that growth doesn’t happen, I think they will endure some pain on the valuation front.”

Questions about the spending power of Indian consumers were raised this year when food delivery start-up Zomato closed down operations in 225 Indian cities, citing poor demand. Research firm Redseer estimates that online retail in India grew 27 per cent on the year in 2022 to 4.4tn rupees ($53bn), down from 45 per cent growth in 2021 when the pandemic fuelled demand for digital services.

“The [Covid-driven] uplift is gone for a variety of businesses and their growth has suffered. Hence, the valuations have come down to reflect this,” said Anand Prasanna, managing partner at venture capital firm Iron Pillar. “This will definitely create more challenges for the marked down companies to raise new up rounds immediately.”

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on May 25 2023. ©2023 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved.

Related Stories