Households across Europe are facing a persistent pinch from one of the worst cost of living crises since the second world war, despite inflation falling almost as quickly as it rose.

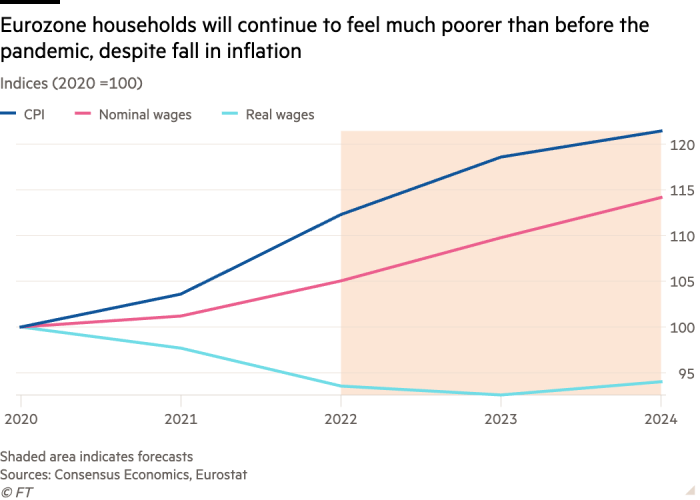

Even by late next year, real incomes will not have regained the levels they reached before the surge in price growth, according to analysis by the Financial Times based on official figures and projections from Consensus Economics, a forecast aggregator.

Real incomes fell by 6.5 per cent between 2020 and 2022 in the eurozone due to surges in energy and food costs. By the end of 2024 they will remain 6 per cent below 2020 levels, according to the analysis.

Price pressures in Europe are fading as the impact of last year’s rise in energy costs falls out of the annual headline calculation. Figures due to be published on Tuesday are expected to show the headline measure of annual inflation for the eurozone dipped to 6.8 per cent last month.

The falls ease the pressure on policymakers at the European Central Bank, who increased interest rates aggressively throughout 2022 to combat price pressures and are expected to slow the pace of monetary tightening when they meet later this week.

However the ebbing phase of high price growth will leave a lasting drag on households’ finances, analysts warn.

“Although inflation rates look set to ease, prices are not coming down,” said Victoria Scholar, head of investment at Interactive Investor, an online investment service. “The squeeze on households’ budgets and cost-of-living pressures could continue to be a notable headwind.”

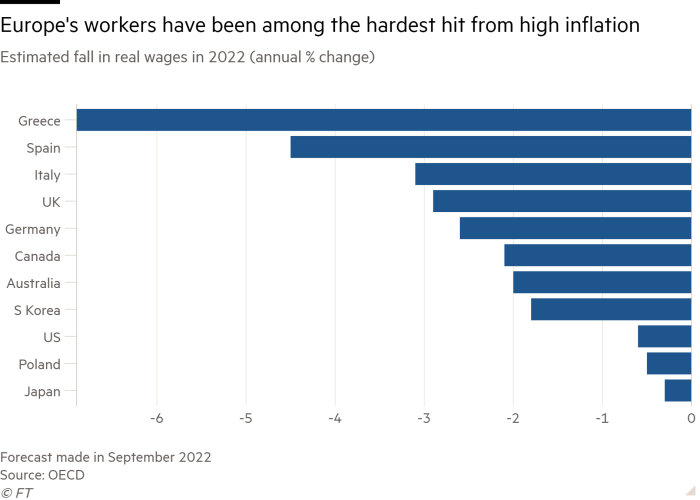

In major eurozone economies, including Germany and France, the region’s two largest unions have resorted to strike action in a bid to compensate workers for higher prices.

“Any easing of inflation is good news for working people but we’re still far from the end of this crisis,” said Esther Lynch, general secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation. “With wages so far behind the cost of living for so long, pay rises are still needed to restore lost purchasing power, especially in those companies which have made record profits.”

Poorer people, who spend a bigger chunk of their income on essentials, have been most exposed to the rise in prices. They will continue to feel the squeeze hardest, with food costs continuing to soar even as energy prices fall.

In the EU, food costs rose by 19.5 per cent in the year to March, the highest rate since Eurostat started collecting such data in 1997.

In some member countries — including Poland, Portugal and the Baltic states — costs have surged even more. The prices of some staples such as cooking oil and eggs have risen more than 30 per cent within the bloc in the year to March.

Some EU governments have intervened. France struck a deal with supermarkets to offer cut-price offers on staples, Croatia has capped the price of eight essentials from milk to chicken, while Portugal has joined Spain and Poland in slashing food taxes.

This has not stopped increasing numbers of people turning to charities for support.

Katja Bernhard, a board member of the food bank association for Germany’s Hesse region, said the influx of applicants in recent weeks was so high that half of its 58 establishments had to stop taking on more people — up from a third of them late last year.

“The demand is still high and the number of customers is increasing,” said Bernhard.

The same drag is set to hit workers in Britain, too. The UK’s fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, estimates that the period from the spring of 2022 to the spring of 2024 will mark the steepest decline in people’s real disposable incomes since records began in the 1950s.

The official cap on British households’ energy costs is set to fall to £2,200 by the end of 2023 from more than £3,280, reflecting a drop in the European wholesale gas price from its peak in August. But this level would still be double the figure for 2020.

“Prices will remain high and wages must recover their lost value after the longest wage squeeze in 200 years,” said Paul Nowak, general secretary at Britain’s Trades Union Congress. “For families to feel better off, the government must reward work instead of wealth.”

Anna Taylor, executive director at the Food Foundation, a UK-based non-profit organisation, said: “The persistent increase in food prices month after month is having a devastating impact on people’s ability to feed themselves and their families.”

The headline rate of price growth in both the eurozone and the UK is not expected to return to the 2 per cent level the ECB and the Bank of England target until next year, according to Consensus Economics forecasts.

Nathan Sheets, chief economist at US bank Citi, said the “global consumer is likely to be feeling better during the first half of next year [when] inflation should be declining and any associated recessionary pressures likely to have largely passed”.

Additional reporting by Mary McDougall in London