The rush to buy books documenting Marcos’ destructive 21-year reign comes as his son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., assumes office after a landslide election victory in May.

Marcos Jr. has never publicly acknowledged or apologized for the human rights abuses, corruption and theft that historians say took place under his father’s leadership.

And there are fears that now he is in power, he will try to rewrite history.

Journalist Raissa Robles, the author of “Marcos Martial Law: Never Again,” said after Marcos Jr.’s win she received emails from readers all over the world with requests to reprint the detailed dive on the victims of martial law.

“The book price had nearly doubled and yet the people were buying the book by batches. They weren’t just buying one or two. They were buying five or 10 at a time,” Robles said.

The main cause for concern came from the president himself.

“We have been calling for that for years,” Marco Jr. said in a forum hosted by the National Press Club, as he accused those in power since his father’s demise of “teaching children lies.”

The family has repeatedly denied using state funds for their personal use — a claim challenged in multiple court cases.

CNN reached out to the new Marcos government for comment but has not received a response.

Demand surges for books on the Marcos regime

“He got it done. Sometimes with needed support, sometimes without. So will it be with his son — you will get no excuses from me,” he said.

“What we teach in our schools, the materials used, must be retaught. I am not talking about history, I am talking about the basics, the sciences, sharpening theoretical aptitude and imparting vocational skills,” he said.

But those assurances ring hollow for people who suffered under his father’s dictatorship, and others who are skeptical of the new Marcos leadership.

One indication of that is through book sales.

“People were suddenly fearful that literature critical of the dictatorship would be banned,” Manduriao said. “Hence, the need to buy and safeguard the books (when) they still can.”

At least 10 titles covering martial law and the dark past of the Marcos dictatorship remain sold out at the university press, according to Manduriao.

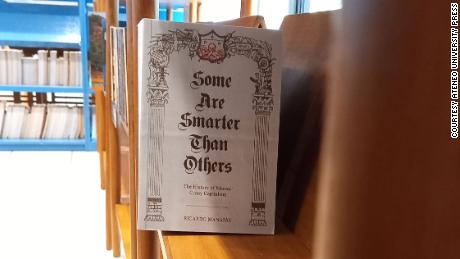

Some of the bestsellers at the campus bookshop were in reprint — namely “Some Are Smarter than Others: The History of Marcos’ Crony Capitalism” by Ricardo Manapat, “The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos” by Primitivo Mijares and “Canal de la Reina” by Liwayway Arceo Bautista.

In the days that followed, sales went through the roof and the pre-order waitlist grew, and the company announced it might take as much as eight weeks for orders to be delivered.

The offer was a hit with customers, but it also attracted the attention of the government.

Alex Paul Monteagudo, director general of the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency, accused Adarna House of “radicalizing Filipino children.”

“The Adarna Publishing House published these books and they are now on sale to subtly radicalize the Filipino children against our government, now!” he wrote on his official Facebook page on May 17.

Monteagudo said in the post that when topics such as martial law and the People Power revolution — a nationwide uprising that overthrew the Marcos regime in 1986 — are taught in schools, it will “plant seeds of hatred and dissent in the minds of these children.”

Adarna House declined CNN’s request for comment on the claims.

One of Adarna’s customers, Vanessa Louie Cabacungan-Samaniego, who lives and works in Hong Kong, put in a group order for around a dozen Filipinos in the city for books on the Marcos dictatorship.

She told CNN she worries the election will allow the Marcos political clan to “work to clear their name and revise history books or target the media.”

“Buying books to educate ourselves and the next generation is just our small way to fight against injustices,” she said, when the first batch of orders was delivered in June.

Preserving the truth

In recent years, politicians and government officials have demonized publishers and journalists, denouncing their credibility on social media and in public statements.

“This is intimidation. These are political tactics. We refuse to succumb to them,” she said.

Michael Pante, a history professor at the Ateneo de Manila University, said he feared Marcos Jr. would continue former President Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign to delegitimize the work of historians, academics and journalists — and potentially move to rewrite history books.

Reporters Without Borders said that since Duterte’s election in 2016, media have been subjected to verbal and judicial intimidation for work deemed overly critical of the government.

“The demonization of historians, academics (and journalists) will continue,” Pante said. “And the dismissive attitude (toward them) will be enough to generate fear of speaking up and getting arrested or censored.

He fears that if the stories of martial law survivors are forgotten, people will be once again susceptible to political violence.

His team of about 30 people plus 1,500 university student volunteers — most of them are half his age and have not lived through martial law themselves — was chosen to protect the truth for the next generation.

“I want to have part of this digital archive available to the public, in a way that (can be) easily accessible, to be sent to colleges here in the country and also some partner institutions abroad, so that the memory and evidence will never be lost,” he said.

“If there’s one lesson state authorities learned from the martial law period, it’s that no one (has to) go to jail, even if they commit gross human rights violations,” he said.

Robles, the author, said people had told her they wanted to give copies of her books to relatives, while others wanted to stash away a supply in case the new government bans reprints.

“They said they want to hide it so that after the Marcos presidency, then they can bring it out and keep the memory alive,” she said.

Robles said she is determined to keep writing and critiquing the nation’s political landscape, despite fears of censorship — but she admits, “I’m not just afraid of censorship, I’m afraid of being arrested.”