Ottawa couple Mario and Jennifer Bazinet lost their first son — Beau Paul — at three and a half months old. Mario went to get his son and found him lifeless in his crib on Dec. 13, 2020.

“Our world flipped upside down,” said Mario, 31. Jennifer, 29, now volunteers for Baby’s Breathe Canada, a foundation devoted to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), the official cause of her son’s death.

“When a baby dies unexpectedly it’s just not the right order of how life goes,” she said. “Your whole world falls apart.”

Thousands of Canadian families face this gut-wrenching grief, and though Canada’s infant mortality rates have improved over time — from about 10.9 deaths out of 1,000 births in 1980 to 4.4 deaths per 1,000 births in 2021 — the country has slipped in its ranking of infant mortality among wealthy, developed nations, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Canada went from ranking 10th out of 24 OECD countries in the 1980s to 30th out of 38 OECD nations in 2021.

Healthy policy experts and analysts say that’s a red flag about the state of the country’s social safety net, and that Canada’s lower ranking reflects issues considered risk factors for infant deaths. These include lack of education and housing, poor access to food and health care, plus poverty and unemployment, according to the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative.

In Canada, the leading cause of infant deaths are linked to low birth weight, birth defects, oxygen deprivation, infection and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

According to health policy experts, the rate of infant mortality is a key indicator of the overall health of a country’s population.

‘Heartbreak on repeat’

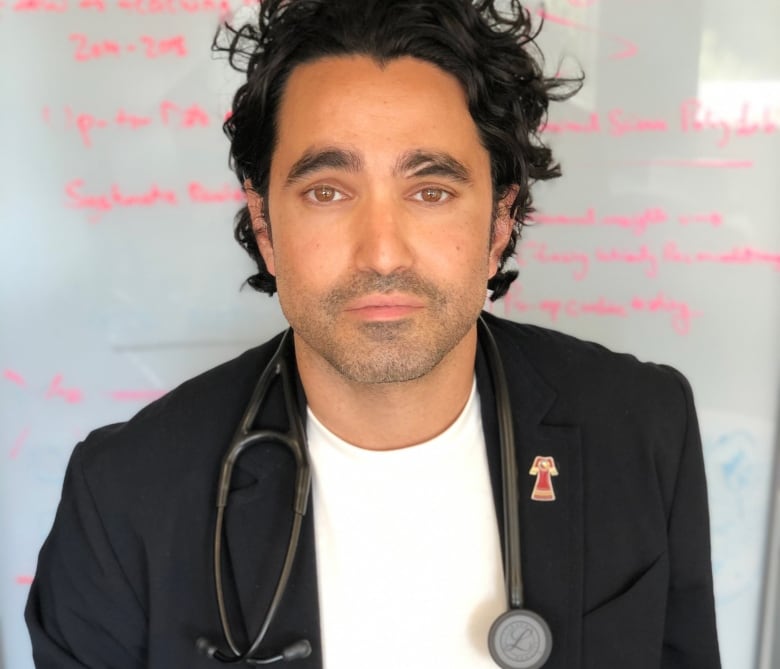

“This is heartbreaking. It’s been heartbreak on repeat for patients and families and communities for many decades now. And I think we’re seeing it only get worse,” said Dr. Andrew Boozary, a primary care physician in Toronto and the executive director of Population Health and Social Medicine at the University Health Network.

Boozary says people often wrongly blame themselves for health outcomes that are driven by social determinants such as poverty or lack of access to health care.

“We have fundamentally worse health outcomes than almost all other countries — other than the United States,” he said.

“It’s the willingness to accept these outcomes that I find is actually most damning … it cannot be any more stark than life and death for infants.”

How infant mortality rate is determined

Around the world, data is collected on infant mortality, which is defined as the death of children under one year old. This standard is used to report trends by the Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality of Estimation, which includes representatives from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations.

There are international variations in how that data is collected that critics say affects the rankings.

For instance, in Canada and the U.S., all babies that are born alive must be registered, but many European countries do not record babies who die before they reach 24 weeks of age in their overall infant mortality rate, according to a 2012 study by four Canadian universities and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

But even accounting for that, experts say Canada’s slipping ranking is a warning sign.

Ranking slipping for decades

Canada’s trajectory is “striking,” according to Dennis Raphael, a professor at the School of Health Policy and Management at York University.

In the past four decades Raphael notes that Canada has continually slipped in the rankings of infant mortality in OECD nations: from 10th out of 24 countries in 1980, to 26th out of 34 countries in 2011, and finally to 30th out of 38 countries in 2021.

Raphael, who is busy compiling the latest edition of the book he co-authoured, The Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts, calls that ranking “dismal.”

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health as the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.

This includes everything from neighbourhoods and living conditions to the economic policies and funding for social supports.

How systemic failures affect racialized families

Boozary noted that poverty and systemic racism are driving up preventable infant deaths. Research has shown that systemic failures hit low income and racialized families the hardest.

“It’s a national concern,” he said.

By 2021 the Canadian non-Indigenous infant mortality rate was 4.4 deaths per 1,000 births. The Indigenous infant mortality rate was more than twice that, at 9.2 deaths per 1,000 births.

“We’ve got an infant mortality issue,” said Raphael, noting that high infant mortality rates in Canada are usually framed as an Indigenous issue, as rates for Indigenous infants are more than double non-Indigenous mortality rates.

“I was able to find the infant mortality rate from a Canadian government document for non-Indigenous, and we’re still pretty bad.”

Dr. Janet Smylie, a Métis physician and research scientist who is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Advancing Generative Health Services for Indigenous Populations in Canada, says infant death is a measure of the health of a society.

“It’s a loss of potential. And we know that it’s linked to equity measures,” she said.

There have been numerous studies linking high infant mortality to systemic racism and other inequalities such as poverty and lack of access to health care.

Smylie said the number of Indigenous infants that die is likely an undercount due to the lack of quality data collected, leading to a failure to recognize some infants as Indigenous.

“It could quite well be that disparities in First Nations, Inuit and Métis infant mortality are still driving this,” she said. “But we don’t know because we don’t have quality information about infant mortality or birth weight in this country.”

Low birth weights

The rate of infants born at low birth weights — another good predictor of underlying health issues — has also worsened in the past decade, according to health policy analysts.

Canada’s comparative performance for low birth weight rate slipped from 12th out of 34 OECD nations in 2013 to 19th out of 37 nations by 2019.

Infant birth weights that are lower or higher than the average can be predictive of health issues that can persist into adulthood.

A baby’s birth weight is affected by many factors, including the mother’s stress levels and nutrition and health concerns, such as diabetes. In Canada, newborns weighing about 3.5 kilograms (7.5 pounds) to 4.5 kilograms (10 pounds) are considered within the normal range.

According to a Stats Canada study of close to six million births in Canada released in January 2022, the average birth weight of babies decreased between 2002 and 2016.

When it comes to Canada’s low infant mortality ranking, Raphael believes it is a “canary in the coal mine” signifying other problems with Canadian institutions overall — from the strained health-care system to a lack of social supports to low wages that haven’t kept up with the cost of living.

He suggests that the infant mortality rate will keep rising across the country as people fall through rips in the social fabric he says have resulted from the tax cuts and claw backs of the 1990s.

Raphael and Boozary suggest the best way to counter these rates and reverse the country’s slipping ranking is to stop chipping away at those social programs and instead concentrate on pre-natal care by providing better access to health care and family doctors, and working to improve housing, food insecurity, wages and mental health supports.