A global movement to grant rivers legal personhood recently reached Canada, and a local Indigenous leader is asking whether the Gatineau River could be next.

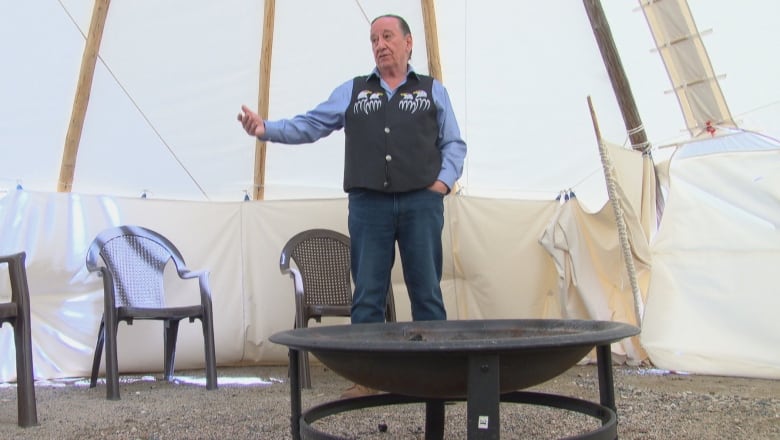

Former Kitigan Zibi Chief Gilbert Whiteduck said such legal designation would provide the Gatineau River better environmental protection, and he’s “pushing” to make it a reality.

The movement, which is largely led by Indigenous communities, environmental groups and scientists, is designed to afford rivers and other ecological features stronger legal protections by granting them rights normally reserved for people.

“I believe that, as an Algonquin Anishinaabe, we need to work together to protect the land,” Whiteduck told CBC’s All In A Day.

“A lot of people that I’ve met — older people, family members — say yes, this is something we can do together.”

Whiteduck said the Gatineau River is a culturally and historically significant waterway for the Algonquin Anishinaabe people, and local groups may soon attempt to follow Indigenous bands from around the world by expanding the river’s protections through the emerging tool of environmental rights.

‘Part of the planet’

The global movement to grant rivers legal personhood began in New Zealand in 2014.

After decades of fighting land claims related to the Whanganui River, a Māori nation won a legal settlement in 2021 that granted the river the legal rights of “an indivisible and living whole” — in other words, a person.

This settlement was the first example of courts extending legal personhood to a non-human or inanimate object.

Since then, hundreds of similar rights-based environmental protections have appeared around the world, although these efforts have been largely concentrated in New Zealand, the United States and Ecuador.

The approach first reached Canada with the protection of the Muteshekau-shipu, or Magpie River, in Quebec’s Côte-Nord region.

In February 2021, the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit and the Minganie Regional County Municipality passed parallel resolutions that assigned the river nine legal rights, including the right to be preserved and the right to take legal action.

As a result, the legal status means the body of water — represented by “guardians” appointed by the regional municipality and the Innu — could theoretically sue the government.

“We have been thinking that we are masters of the world,” said Yenny Vega Cárdenas, a Quebec lawyer and president of the International Observatory on the Rights of Nature. “We need to understand that we are not the master, but we are part of the planet.”

Last week, Cárdenas joined both the chief of the Ekuanitshit council and the mayor of Minganie in a presentation on legal protections for the Magpie River at the United Nations water conference in New York City.

What about the Gatineau River?

Cárdenas said she wonders whether the Magpie River may produce a “butterfly effect” in Canada — the idea that a small movement can have larger effects elsewhere.

Although Cárdenas wasn’t aware of an attempt to grant the Gatineau River legal personhood, she added she’s “happy” to hear the project may be gaining traction.

“The physical goal is to make rivers fishable, drinkable and swimmable,” she said. “It’s not very difficult, but at this time, rivers are not able to fulfil those expectations.”

The Friends of the Gatineau River wrote in an email to CBC that it’s too early for the organization to discuss its potential involvement, but added that it would be in touch when the project is ready to launch.

Cárdenas is currently pushing for the St. Lawrence River to be recognized as a legal person by both Canada’s Parliament and Quebec’s National Assembly.

“The status quo is no longer acceptable,” she said. “We need to have a strong water law framework, and I think legal personhood is the future for water around the world.”

Whiteduck is hoping to channel the same framework a little further upstream.

“I’m pushing, and I’m trying to sow the seed that Gatineau River would receive that,” he said. “I believe we need to protect it.”